In April, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced an ambitious plan to phase out the use of animal tests in preclinical drug testing, signaling a significant shift in the pharmaceutical industry. The agency aims to make animal studies “the exception rather than the norm” within the next three to five years, beginning with monoclonal antibodies and eventually covering all drugs. This change could include fast-tracking regulatory reviews for studies that utilize alternatives to animal testing.

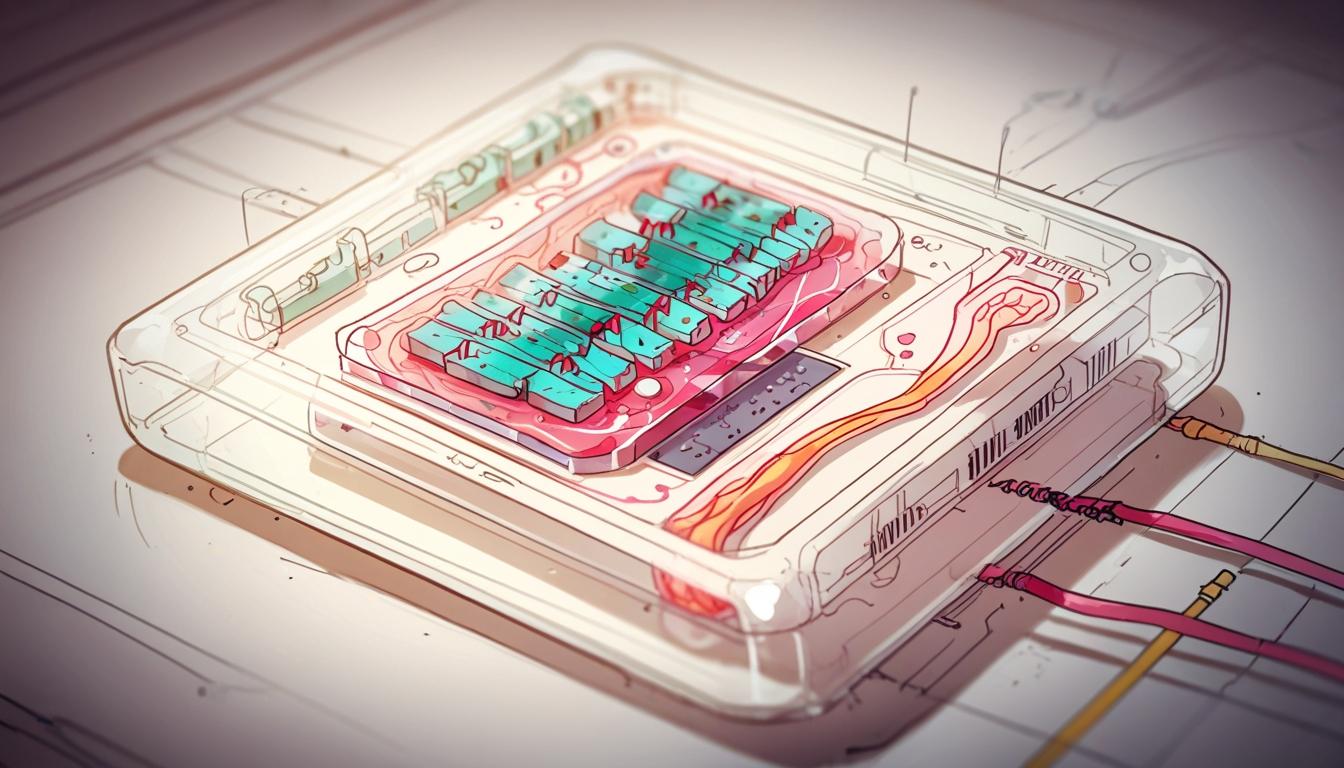

Jim Corbett, CEO of the organ-chip developer Emulate, has seen a surge in interest from potential clients and investors following the FDA's announcement. Emulate produces organ chips—tiny, thumb-drive-sized devices lined with living human cells that replicate functional tissue interfaces within organs. The technology was initially developed at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering by Don Ingber and his team. Emulate’s liver chip, for example, features hepatocytes on one side and capillary cells on the other and demonstrated the ability to correctly identify 87% of hepatotoxic drugs in a 2022 study cited by the FDA.

The FDA's roadmap represents a clear shift in regulatory policy. Corbett noted, “This is a clear and deliberate shift,” highlighting the agency's commitment to moving away from reliance on animal models. Tomasz Kostrzewski, chief scientific officer at organ-chip maker CN Bio, described the announcement as a “key watershed, historic moment,” stating it marked a firm declaration by the FDA to embrace alternatives within a multi-year timeline.

Traditionally, drug safety and efficacy have been assessed using animal models such as rats, mice, dogs, and nonhuman primates. However, these models have limitations in predicting human responses; nearly 90% of drug candidates tested on animals fail in clinical trials. Additionally, maintaining and using animals for testing raises ethical concerns.

Alternatives like organ chips and organoids—miniature, lab-grown human tissue equivalents—offer promising complements or replacements to animal testing. For instance, AxoSim, a company developing brain organoids, grows human neurological cells into 3D structures that mimic brain functions representative of different human ages. AxoSim’s CEO, Alif Saleh, said, “The idea that a mouse brain or a rat brain or any other animal brain can predict how a human brain would react to a particular drug—it's not credible. Yet up until this point, this has been the only solution that pharma has had available to them.” Takeda Pharmaceuticals has tested AxoSim’s microbrains with a panel of 84 known drugs, finding the system useful as an early screening method for neurotoxicity.

Several pharmaceutical companies have started integrating such technologies into their development pipelines. Emulate partners with Moderna for safety screening of lipid nanoparticles, while Hesperos collaborates with companies including Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Argenx, and Apellis Pharmaceuticals to test drug candidates for safety and efficacy in neurodegenerative and other diseases. Hesperos’s chief scientist, James Hickman, noted that some compounds evaluated with their platform are progressing through clinical trials.

In addition to biological models, computational methods like artificial intelligence and in silico simulations are expected to complement organ chips and organoids. Corbett emphasised the importance of integrating multiple methods, saying, “Artificial intelligence and in silico models… will have a place at the table, without a doubt.” Tina Morrison, vice president of scientific strategy at EQTY and former senior adviser at the FDA, supports the use of organ chips alongside computational models for drug safety assessment.

Combining models may help address concerns about drug side effects in organs other than the primary target. Don Ingber’s Wyss Institute has developed a system linking about 15 different organ chips, forming what he calls a “human body on a chip.” This system can quantitatively predict a drug’s pharmacokinetics, helping to inform and potentially expedite clinical trial design.

Despite technological advances, safety remains a critical concern. An anonymous former FDA official warned that adoption of new testing methods “could be set back by any patient deaths that are associated with a drug tested using a prematurely adopted model.” Hickman underscored this risk plainly: “If you fail on safety, people get really upset. That could set the field back years.”

Incorporating the immune system into organ models is another frontier. Thomas Hartung, director of the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing at Johns Hopkins University, emphasised the importance of including immune cells, saying, “There’s essentially no disease in which inflammation plays no role. There’s no toxicity without it. But if you know it, you can build it in as an engineering system.” He also identified potential synergy between organoids and AI in mimicking cognitive functions and complex behaviours typically studied in nonhuman primates.

Financial investment and policy support will be crucial for the transition. The former FDA official cited the need for congressional funding and public-private partnerships, noting that recent legislative efforts like the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 and its reintroduced 3.0 version have not included increased funding. Research and development efforts have also faced challenges under the current US administration, with some organ-chip projects and government contracts experiencing pauses or stop-work orders.

In the pharmaceutical sector, biotech firms are seen as the quickest adopters of non-animal models due to their agility and singular focus on specific diseases or modalities. Larger pharmaceutical companies, despite slower processes, have begun integrating alternatives into their pipelines, backed by deeper financial resources.

Contract research organisations (CROs), which historically conduct much animal testing for drugmakers, may represent a major hurdle. Kostrzewski of CN Bio described CROs as “entrenched in the standard ways of working” and reluctant to move away from animal assays that have provided steady profit margins. The stock of Charles River Laboratories, a major player in animal testing, fell sharply following the FDA announcement, though the company has since highlighted efforts to develop “humanized platforms” through tumoroids, cell assays, and AI technologies.

Overall, the FDA’s recent policy shift marks a pivotal moment for drug development, creating opportunities for organ chips, organoids, computational models, and other technologies poised to transform the landscape of preclinical testing.

Source: Noah Wire Services