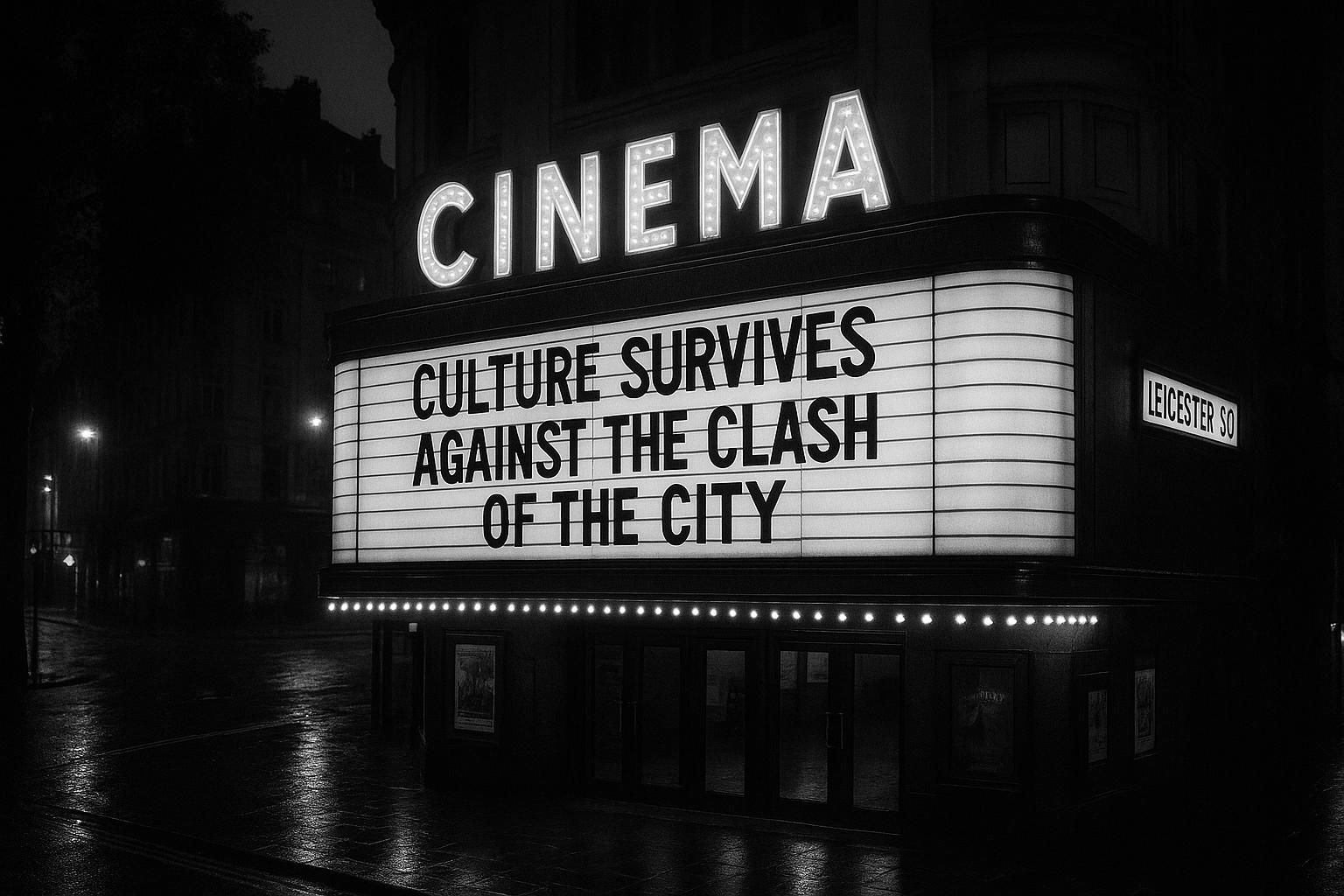

When London’s Prince Charles Cinema has something to say, it makes its voice heard loud and clear. Known for its quirky marquee messages, it once cheekily declared during a summer heatwave: "SOD THE SUNSHINE COME SIT IN THE DARK." However, the famed Leicester Square venue now finds itself embroiled in a high-stakes tug-of-war, its future hanging in the balance against the backdrop of a fierce power struggle with its landlord, Zedwell LSQ Ltd, a subsidiary of Criterion Capital.

The cinema, which has been part of the cultural fabric of London since the 1960s, made headlines on 28 January when it launched a petition urging the public to rally for its survival. The venue lambasted its landlord for allegedly employing its "significant financial resources" to intimidate it into accepting unsustainable terms that included a staggering rent increase, a reduced lease duration, and a break clause allowing for its eviction with a mere six months' notice. This dispute has resonated deeply with the public, garnering over 135,000 signatures in support of the cinema within a day. Notable figures from the filmmaking world have also chimed in, with Christopher Nolan commenting that "film culture in Great Britain is unthinkable without the Prince Charles," and Danny Boyle asserting that the closure of this cultural landmark would signify a profound loss for London.

As this battle unfolds, attention is drawn to Asif Aziz, the owner of Criterion Capital, who has often been dubbed "Mr West End." While the escalating clash has spotlighted Aziz, discomfort simmers beneath the surface, with experts suggesting that the ongoing crisis at the Prince Charles Cinema reflects broader issues plaguing London's cultural landscape. As Kate Mossman articulated in the New Statesman, London's West End faces a relentless assault from powerful developers, with little regard for cultural preservation. This sentiment is echoed by urban governance experts, who argue that the commercial interests of a select few threaten to erode the very essence of the city's cultural diversity.

Despite the whirlwind of public commotion, Aziz—whose nickname was first coined for his ambitious real estate endeavors—has remained relatively reticent. However, revelations about his dealings indicate a more complex portrait of a man who has risen remarkably from humble beginnings in Malawi to hold sway over significant parts of London's property landscape. Critics point to his past controversies, including accusations of letting properties deteriorate while their values appreciated, creating a difficult relationship with both local communities and the press.

Within this context, the Prince Charles Cinema's managing director, Ben Freedman, has spent considerable time negotiating new lease terms with Aziz. Freedman maintains that his cinema, covered by the Landlord and Tenant Act (1954), is entitled to a new lease at a fair market rate. But as negotiations drew out over months—featuring back-and-forth conversations that increasingly felt like bidding wars—the situation warmed up when Criterion announced its demands for an increase that nearly doubled the current rent. Meanwhile, Freedman learnt through independent assessments that the existing rent was indeed reasonable—not that this revelation tempered Criterion’s demands, which continued to escalate.

The trajectory of these negotiations echoes a larger theme of urban development in London, where property ownership increasingly reflects wealth concentration among a small elite. According to scholars, such as Mike Raco at UCL, the accumulation of property by affluent developers has led to a commodification of spaces at the expense of their cultural and community significance. This "hollowing out" of the West End manifests not solely through rising rents but also in the proliferation of corporate establishments displacing cherished local businesses.

Aside from the Prince Charles, other institutions are similarly threatened. The fate of the Central YMCA, rich in community history, serves as another cautionary tale of how powerful property players can eclipse cultural touchstones. With its unexpected closure, many community members have expressed a profound sense of loss for what once served as a hub for local interactions and support.

In a recent turn of narrative, the Prince Charles has been recognised as an asset of community value by Westminster Council, a critical designation that acknowledges its cultural significance and complicates Criterion's redevelopment ambitions. For Freedman, this official recognition bolsters the cinema's stance. However, the road ahead remains uncertain, with legal battles looming in the backdrop should a resolution not be reached, underscoring the persistent struggle of cultural institutions against the relentless forces of commercialism.

Asif Aziz paints a different picture, suggesting that the media portrayal of his dealings has often simplified a complex issue to personal animosity towards him. In a brief exchange, he highlighted his philanthropic efforts through the Aziz Foundation to support the local Muslim community and preserve cultural monuments, arguing that such contributions inherently align with his business interests.

For David Beida, a longtime community organiser in Soho and a vocal advocate for preserving local heritage, the current disconnect between Criterion and the community reveals a deeper rift. He critiques Aziz’s operations, suggesting they prioritise profits over the cultural equilibrium crucial for maintaining vibrant local life.

As London brims with its standard blend of cultural allure and fraying community ties, the struggle at the Prince Charles Cinema exemplifies the larger battle to safeguard local identity amid commercial encroachment—a conflict, it seems, far from resolution. In an environment where property ownership continually dictates not just market dynamics, but also the very heartbeat of community life, Freedman and those who rally around him embody the assertion that engaging in this fight is not merely about saving a cinema but about preserving a cultural legacy.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 3 – [7], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 5 – [5], [4]

- Paragraph 6 – [2], [1]

- Paragraph 7 – [6], [2]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 9 – [7]

- Paragraph 10 – [4], [5]

- Paragraph 11 – [1], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services