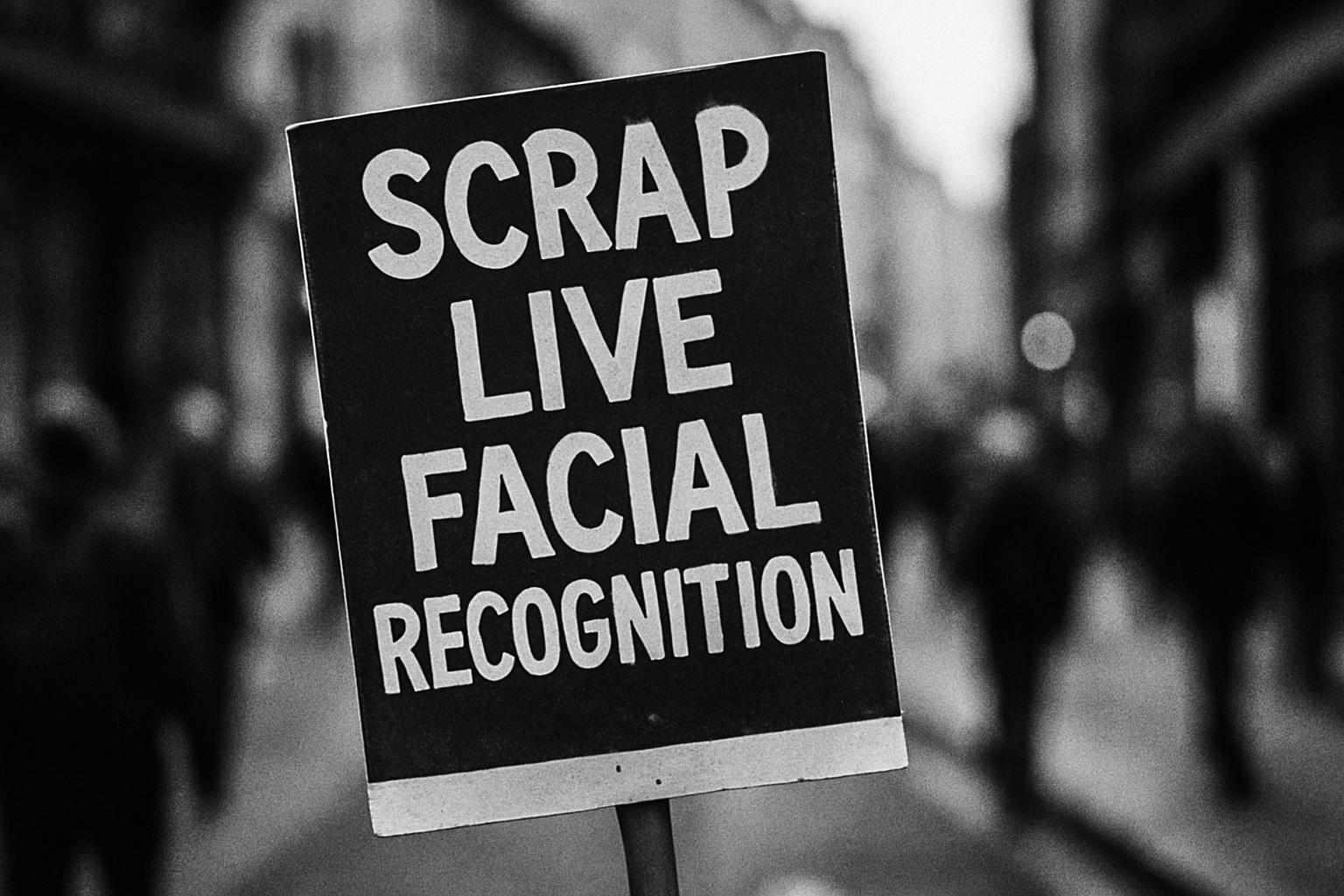

Alba Kapoor of Amnesty International UK has urged the Metropolitan Police to abandon plans to expand live facial recognition, arguing the technology will further entrench racial discrimination in policing and put basic civil liberties at risk. Writing in The Guardian on 8 August, Kapoor said the systems are already known to misidentify people from marginalised communities and warned that deploying them more widely at events such as Notting Hill Carnival threatens the rights to privacy, peaceful assembly, expression and equality. She called for the Met’s plans to be scrapped immediately.

The Met says it intends to increase the number of live facial recognition deployments significantly, from a handful of uses across two days to multiple operations over an extended period, a change explained by force officials as a response to budget cuts and reductions in officer numbers. Police spokespeople argue the technology helps to identify wanted offenders at public events, but campaigners counter that scaling up a system with known error rates risks producing more false matches and more intrusive stops.

The human cost of those false matches was underscored by recent reporting about Shaun Thompson, a community worker who was wrongly flagged while returning from a volunteering shift. According to the BBC, officers detained and questioned him for some 20 to 30 minutes, requested fingerprints and identity documents before accepting his passport and releasing him; Thompson told the BBC the episode was “intrusive” and that he felt he had been “presumed guilty.” Such incidents feed wider concerns that biometric tools can translate algorithmic mistakes into real-world harms.

Technical research provides a clear basis for those concerns. The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s landmark Face Recognition Vendor Test found persistent demographic differentials across roughly 200 algorithms, documenting higher error rates for women and people with darker skin while also noting substantial variation between vendors — with top-performing systems in some tests approaching parity. Earlier academic work, notably the Gender Shades project led by Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, showed the same pattern: off‑the‑shelf systems performed far better on lighter‑skinned men than on darker‑skinned women, a finding that helped catalyse vendor reassessments and wider debate about dataset representativeness and transparency.

Civil society has long warned that technical fixes alone cannot eliminate the human-rights harms of mass biometric surveillance. Amnesty International led a 2021 coalition of more than 170 organisations calling for a global ban on public‑space biometric systems, arguing they enable identification, tracking and single‑out of people without consent and that the risks fall disproportionately on marginalised groups. Against that backdrop, critics of the Met say the absence of a clear legal framework or independent oversight leaves decisions about when, where and how to deploy such intrusive tools to police discretion.

Policymakers now face a choice between imposing strict limits — including moratoria on public‑space deployments, mandatory independent auditing, transparent procurement and stronger data‑protection safeguards — or permitting a continued, ad hoc rollout that campaigners say will reproduce and amplify existing inequalities. The Met insists the technology is a necessary tool for public safety; human‑rights groups and technical experts insist its costs are too high without robust regulation, transparency and redress. For now, Amnesty’s intervention adds weight to calls for immediate restraint while lawmakers and regulators consider whether the existing patchwork of rules is fit for purpose.

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 2 – [3], [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [4], [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [5], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [7], [1], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [3], [5], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services