Eighty years on from the end of the second world war, the life of George Aylwin Hogg — the young British journalist who elected to remain in China during its darkest hours — has resurfaced in public memory on both sides of the globe. This year’s commemorations, timed to coincide with what would have been his 110th birthday, brought together family members, historians and diplomatic representatives in London and have sparked new efforts to preserve and retell a story that has long been central to Chinese accounts of the wartime period. According to coverage of the events, the reunions sought both to honour individual courage and to emphasise the wartime ties between Britain and China. (Sources: Independent, China Daily)

The principal memorial in London was organised by the Chinese embassy in the UK in partnership with cultural and civic groups, and featured speeches that framed Hogg as both a chronicler of Japanese aggression and a selfless educator. Speaking at the event, Minister Wang Qi said Hogg exposed the truth of Japan’s invasion and embodied an internationalist spirit; organisers underlined the broader theme that wartime cooperation helped forge long‑term ties between the two nations. The gathering also included a screening component: CGTN Europe premiered the trailer of a documentary, Witness to War: George Hogg in China, signalling a renewed media effort to bring his story to younger audiences. (Sources: Independent, China Daily, CGTN)

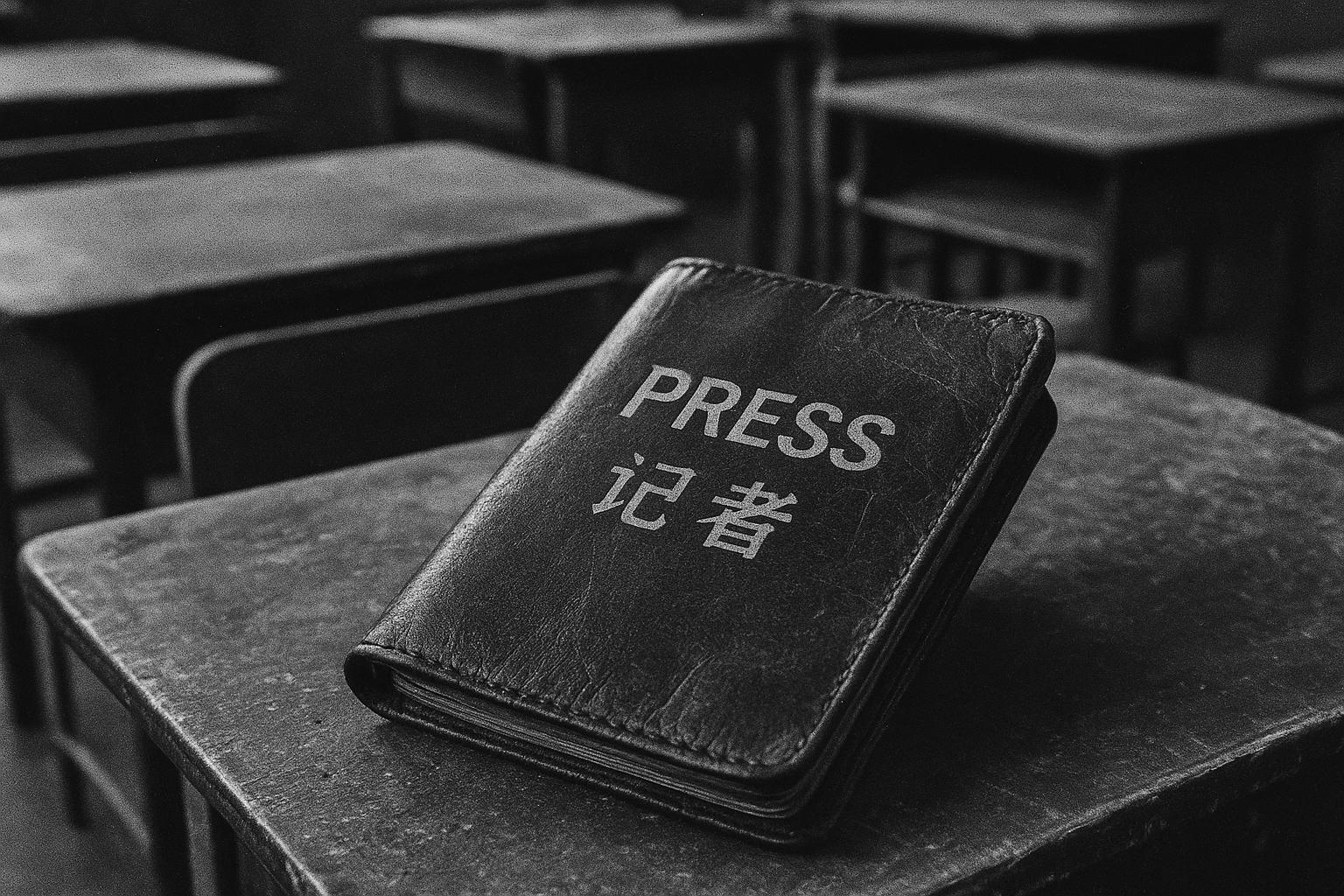

The contours of Hogg’s journey are now familiar: educated in Britain and travelling in the Far East with his aunt Muriel Lester, he arrived in Shanghai shortly after the Nanjing atrocities and remained in China as the conflict widened. His press credentials allowed him rare mobility across wartime zones; he travelled to Yan’an and met senior Communist leaders there, including Zhou Enlai, Zhu De and Nie Rongzhen. Mark Aylwin Thomas, Hogg’s nephew and biographer, has repeatedly reminded audiences that his uncle never sought hero status — “he kind of came to stay in China by accident,” Thomas told journalists — but that the experience transformed him from observer to participant in relief and education work. (Sources: Independent, China Daily, Harpenden History)

Hogg’s most enduring legacy, and the reason he remains a resonant figure in China, was his work with the Bailie School and the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives. As headmaster at Shandan in Gansu province he created a refuge for roughly sixty orphaned boys, many uprooted by war, and is credited with binding children from disparate dialect and social backgrounds into a cohesive community. Drawing on elements of the British school system — houses, teamwork and music — he used singing and shared routines to forge solidarity; Thomas recalled Hogg’s “wonderful baritone voice” and how music, from Chinese guerrilla songs to English folk tunes, became a unifying force. Other accounts note that Hogg adopted several children himself during this period. (Sources: Independent, CGTN, Harpenden History, Wikipedia)

The story of the school’s relocation remains one of the more dramatic episodes in Hogg’s short life. He is associated with the arduous 1944–45 march that moved pupils and staff inland to safer ground at Shandan amid hazardous conditions. Hogg’s sudden death in July 1945, reported to have been from tetanus following a minor wound, cut short his work just weeks before the end of the war in Asia; his fate has been recounted in biographies and local memorials ever since, and has been dramatised in cultural adaptations. (Sources: CGTN, Harpenden History, Wikipedia)

The current wave of remembrances has not relied solely on archival film. Documentary makers have acknowledged a scarcity of moving‑image material and have instead turned to Hogg’s own writings, contemporary testimony and digital reconstructions. The CGTN project has used artificial intelligence techniques to evoke scenes from Hogg’s life, an approach its producers argue will help younger audiences access an episode of history that is often absent from Western wartime narratives. At the same time the Chinese edition of Mark Aylwin Thomas’s biography Blades of Grass was launched at the London Book Fair, and educational groups such as the Society for Anglo‑Chinese Understanding have staged talks and talks and tours that trace Hogg’s route through China. (Sources: Independent, CGTN, SACU)

For historians and activists involved in the commemorations, Hogg’s significance is not only personal but political. Michael Wood, president of the Society for Anglo‑Chinese Understanding, described Hogg’s life as “a real personal story of somebody who was so moved by the sufferings of the Chinese people,” an observation that curators say helps to animate China’s broader wartime contribution — sometimes characterised in Chinese commentary as the “forgotten fourth ally.” Frances Wood, vice‑president of the society, told reporters that Hogg’s story assists in restoring recognition of China’s role during the war. Chinese officials and state media have previously noted Hogg’s prominence in China; President Xi Jinping himself referenced Hogg in 2015, a citation often cited by those organising recent exhibitions. (Sources: Independent, CGTN, People’s Daily Online)

Yet the commemorations also underline an asymmetry of recognition: while Hogg is widely remembered and celebrated in China — with exhibitions, local historians’ projects and pilgrimages retracing his footsteps — he remains comparatively little‑known in Britain outside specialist circles. Organisers of the London events, and those who have published his biography, say the recent spate of documentaries, book launches and lectures aims to redress that balance and to situate Hogg within both humanitarian history and the tangled geopolitics of memory. (Sources: People’s Daily Online, SACU, Harpenden History)

Whatever the future of these portrayals — and some interpretations will continue to reflect differing national narratives about the wartime past — the renewed attention to George Hogg is bringing a life lived between journalism, pedagogy and activism back into public view. Organisers argue that the combination of memorial events, scholarly talks and new multimedia projects will help preserve not only an individual legacy but also a broader acknowledgement of China’s suffering and contribution during the second world war. For now, Hogg’s mixture of practical care for children and insistence on bearing witness remains, organisers say, a small but resonant bridge between two countries whose twentieth‑century histories were irrevocably altered by the conflict. (Sources: Independent, China Daily, CGTN, People’s Daily Online, SACU)

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [2], [3]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [2], [5]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [3], [5], [6])

- Paragraph 5 – [3], [5], [6])

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [3], [4]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [3], [7]

- Paragraph 8 – [7], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 9 – [1], [2], [3], [7], [4]

Source: Noah Wire Services