Charles Burnett’s 1978 film “Killer of Sheep,” long celebrated as a landmark of Black independent cinema, is experiencing a renewed cultural moment, highlighted by a new 4K restoration now playing in theatres across the United States. The film, which Burnett shot on black-and-white 16mm in the early 1970s on a budget of less than $10,000 as his master’s thesis at UCLA, offers a gentle yet profound portrayal of working-class Black life in Los Angeles' Watts neighbourhood.

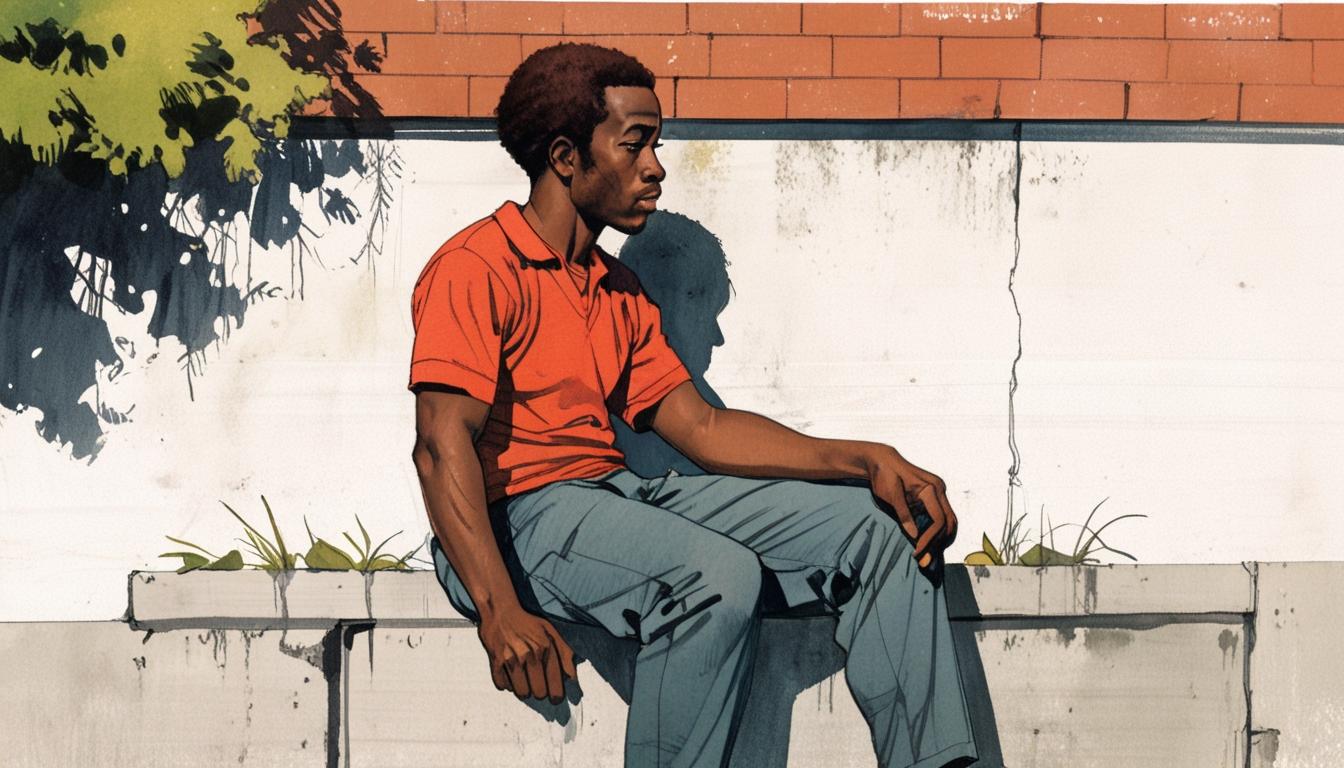

Burnett, now 82, has lived with “Killer of Sheep” for more than half a century, witnessing its evolution from a relatively obscure academic project to a widely recognised masterpiece. The film centres on Stan, played by Henry G. Sanders, a slaughterhouse worker navigating the strains of family and community life amidst systemic challenges. Burnett’s depiction is imbued with soulful lyricism, capturing moments such as slow dances to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth” and the playful freedom of boys leaping between rooftops.

Despite its completion in 1978, “Killer of Sheep” did not receive a broad theatrical release until 2007, the same year Burnett received an honorary Oscar acknowledging his contribution to American cinema. The film's influence has resonated across generations, providing insight into Black experiences and inspiring a lineage of filmmakers.

Burnett’s career has experienced periods of both obscurity and revival. In February, Kino Lorber released his 1999 film “The Annihilation of Fish,” featuring James Earl Jones and Lynn Redgrave, a film that had never before been commercially distributed and was praised as a “quirky lost gem.” Furthermore, Lincoln Center recently launched “L.A. Rebellion: Then and Now,” a film series spotlighting the 1970s movement of UCLA filmmakers like Burnett, Julie Dash, and Billy Woodberry, who fundamentally reshaped Black cinema.

Originating from Mississippi and raised in Watts, Burnett’s work often reflects the environment and community that shaped him. In an interview with The Associated Press upon his arrival in New York for the film’s re-release, Burnett spoke on the tenderness that permeates his films, rooted in the traditions and humanity of the Watts community despite the hardships faced, such as police harassment during the Watts riots. He described the enduring struggles, saying, “In the riots, it wasn't that people got braver. They just got tired.”

Burnett emphasised the focus on future generations in his films, particularly the preparation of children for the harsh realities of the world. He recalled pivotal moments of awareness, such as the broadcast of Emmett Till’s death in Jet magazine, which exposed the cruelty inflicted upon Black Americans and changed perceptions irrevocably. On revisiting “Killer of Sheep,” he described it as “life going by. A life that should have been totally different,” reflecting on systemic barriers, including negative experiences in school and contemporary attempts to diminish the teaching of Black history.

The filmmaker acknowledged the challenges faced within the movie industry, which often lacked welcoming spaces for Black artists. Despite obstacles, he expressed satisfaction with his career impact, noting, “I’m very happy about that. On the flip side, a lot of times you hear, ‘Your films changed my life.’ And if you can get that, then you’re doing good.” Burnett also discussed the necessity of maintaining independence in filmmaking to uphold his vision, sometimes at the expense of frequent work opportunities.

As for the legacy of “Killer of Sheep,” Burnett highlighted the significance of engaging the local community in the film’s production to inspire young people with the message that they too could create. He explained, “I made the film to restore our history, so young people could grow from it and know: I can do this.” He noted persistent challenges, citing ongoing cultural and political battles over representation, such as efforts to undermine diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

Burnett’s reflections present “Killer of Sheep” not only as an artistic achievement but as a continuing dialogue with the past and present struggles faced by Black Americans. The film’s 4K restoration and related retrospectives ensure that new audiences can encounter its poignant exploration of dignity, resilience, and everyday life in the Watts community.

Source: Noah Wire Services