As Britain emerged from the hardships of the Second World War, the nation faced a stringent era of austerity that permeated every aspect of daily life—including fashion. The post-war years saw rationing of not just food but also fabric, which significantly shaped public attitudes toward clothing and style. Against this backdrop, the preparation of Princess Elizabeth’s wedding trousseau in 1947 stirred notable public debate and criticism.

Professor Susan L. Carruthers of the University of Warwick, in her newly published book Making Do Britons and the Refashioning of the Postwar World, explores how, as Britain transitioned from wartime to peace, clothing became a potent symbol of this shifting identity. Between 1945 and 1949, fabric coupons continued to regulate the amount of clothing people could purchase, making new garments a costly luxury relative to prevailing wages. For example, the average weekly earnings for men were just over £6, and for women slightly above £3, while the cost of a woman’s coat could exceed £20—an expense far beyond the reach of many.

This nationwide climate of frugality extended to both men and women. Men returning from service were issued a government-supplied “demob” suit, a symbolic and functional uniform for re-entry into civilian life. Produced by companies such as Sir Montague Burton’s firm, these suits numbered in the millions and included essential accessories, forming a uniform that recognised sacrifice but remained understated.

Women, meanwhile, were urged to “make do and mend,” a campaign epitomised by the fictional character Mrs Sew-and-Sew, who offered practical advice on clothing care amid shortages. Despite this, the conservative styles mandated by rationing contrasted sharply with the arrival of Caribbean immigrants, whose vibrant and abundant fashions clashed with local norms and sparked criticism—highlighting varying attitudes to material use and cultural expression in post-war Britain.

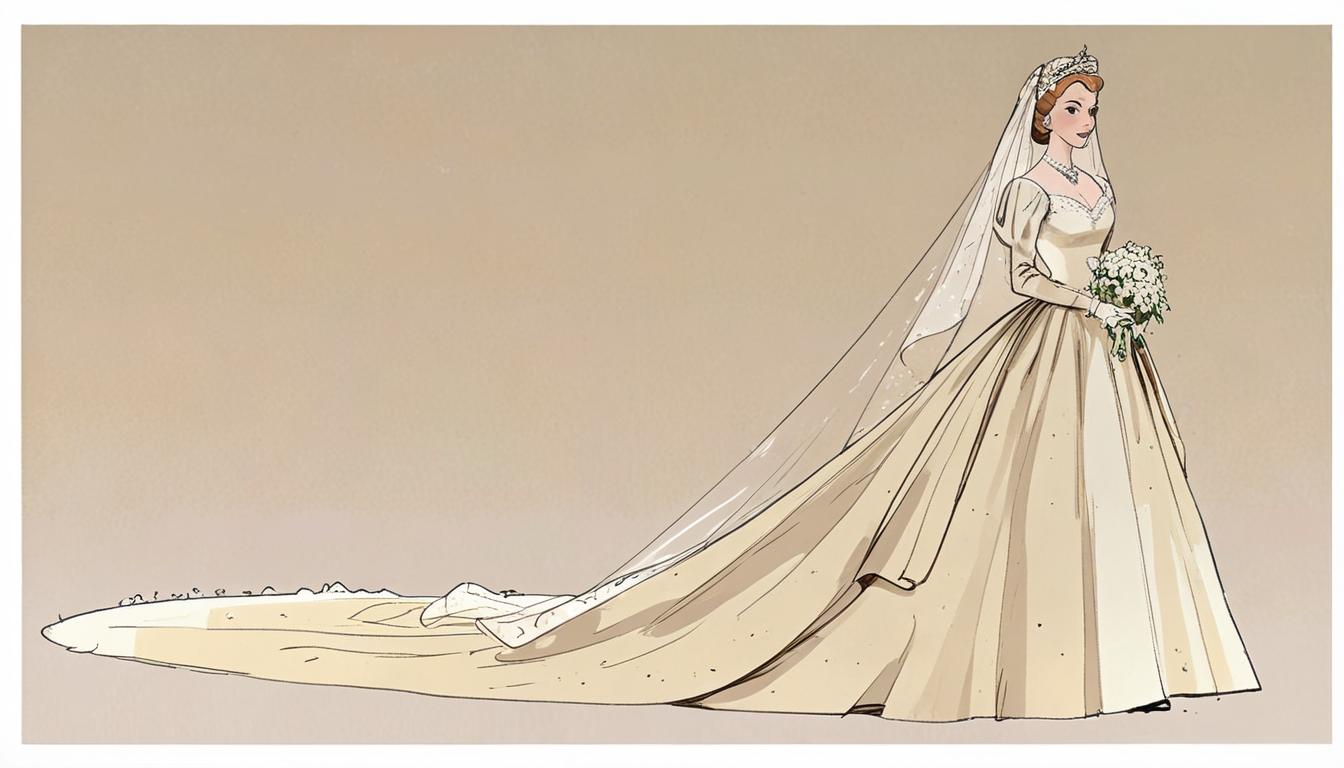

Within this environment, Princess Elizabeth’s wedding preparations became a flashpoint. When she married Philip Mountbatten in 1947, the princess was granted 100 extra clothing coupons specifically for her bridal gown—a decision made by Harold Wilson, then President of the Board of Trade. Some sources suggest the actual number of coupons was even higher. The ivory silk gown, adorned with seed pearls and crystals and featuring a train 13 feet in length, stood in stark contrast to the reality faced by ordinary brides, many of whom wore modest "Sunday best" dresses rather than elaborate white frocks due to rationing and cost constraints.

Professor Carruthers notes: “Austerity sharpened awareness of inequity. Was it fair, some Britons wondered, that Princess Elizabeth received 100 extra clothing coupons for her bridal gown when she married Philip Mountbatten in 1947 while other brides got none?” This sentiment reflected broader frustrations about conspicuous consumption at a time when many citizens struggled just to replace worn garments.

Norman Hartnell, the designer of the royal wedding dress, sought to quell anxieties by reassuring the public about the dress’s materials, stating that the silk was produced from Chinese silkworms—countering rumours that it was sourced from Japan, Britain’s wartime adversary.

As fashion evolved, 1947 also saw designer Christian Dior introduce the “New Look,” with fuller skirts and a return to femininity, marking a departure from the frugality of wartime fashion. Princess Elizabeth’s going-away outfit reflected a careful balance—designed by Hartnell as a blue velour dress and matching coat with a boldly raised hemline, melding austerity with emerging trends.

This period of post-war conservatism set the stage for the more radical sartorial revolutions of the coming decades, culminating in the playful and liberating fashions of the 1960s.

Professor Carruthers’ Making Do Britons and the Refashioning of the Postwar World is published by Cambridge University Press and is available for £25. The Mirror is reporting on these insights into a crucial era of British history, revealing how clothing mirrored the nation’s ongoing economic and cultural adjustments after the war.

Source: Noah Wire Services