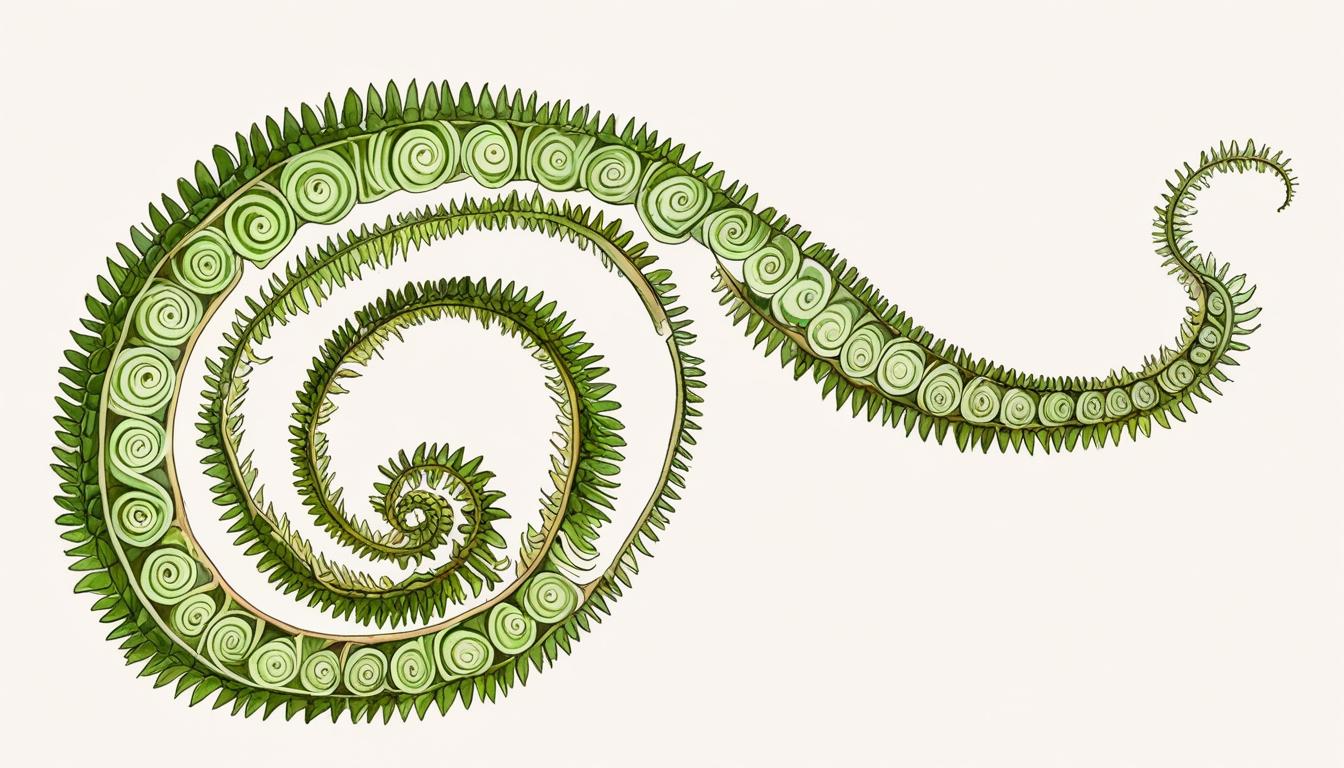

Nature’s intricate designs continue to captivate, as seen in the spiralling unfurling of ferns in gardens this season. In a recent exploration of botanical geometry, the Financial Times highlights how these natural patterns exemplify remarkable mathematical principles.

Ferns, such as the royal fern, tree fern, and polystichums, begin their growth with fronds tightly coiled in spirals—structures referred to as fiddleheads. As these fronds unfold throughout spring and into summer, the smaller spirals of their leaflets also gradually reveal themselves, embodying a repeating pattern of self-similarity where each part mirrors the whole. This intricate design is closely related to fractal geometry, characterised by patterns that repeat at progressively smaller scales.

Natural patterns are not limited to ferns, as emphasised by Edinburgh University plant scientist Dr Sandy Hetherington. Quoting Charles Darwin, he notes: “From so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful . . . are evolved.” Dr Hetherington remarks on the human inclination to find order in nature, which these spirals and other highly ordered plant structures satisfy profoundly.

One striking example is the Romanesco cauliflower, whose spirals demonstrate Fibonacci numbers at multiple fractal levels. The Fibonacci sequence, a series of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8...), is often found in various plant formations. Sunflowers and pine cones display spirals whose counts correspond to adjacent Fibonacci numbers, such as 34 and 55 or 8 and 13 respectively. The Financial Times article suggests observers can use smartphone cameras to capture and trace these spirals, bringing a blend of botanical study and recreational puzzle-solving to the curiosity of nature’s designs.

Beyond simple spirals, plants exhibit helices—three-dimensional configurations where leaves grow in patterns traced along a stem at specific angles. The article points out that the leaves often grow separated by about 137.5 degrees, a value linked to the “golden ratio,” a famous mathematical constant frequently seen in art, architecture, and nature alike. This relationship between plant morphology and mathematical ratios fascinates researchers, although even Charles Darwin found the prevalence of Fibonacci numbers in plants somewhat puzzling.

The article underscores that despite advances in botanical science, many questions about why these patterns exist remain unanswered. Research continues, led by figures such as Dr Michael Sundue of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, who has dedicated his career to studying ferns in diverse environments including South American jungles. His work epitomises the ongoing scientific efforts to understand plant geometry, with new species still being discovered even within cultivated glasshouse collections.

By examining the spirals and helices of ferns and other plants, the article reveals the astounding complexity and order present in the botanical world. These natural patterns offer a window into mathematical beauty and biological form, unfolding quietly in gardens and wild landscapes alike. The discussion reflects insights drawn from the book Do Plants Know Math? by Stéphane Douady, Jacques Dumais, Christophe Golé, and Nancy Pick, published by Princeton University Press, which explores these relationships in accessible detail.

For those interested in further exploration, the Financial Times invites readers to observe these natural phenomena firsthand, noting the continuous botanical wonders emerging in gardens during the growing season.

Source: Noah Wire Services