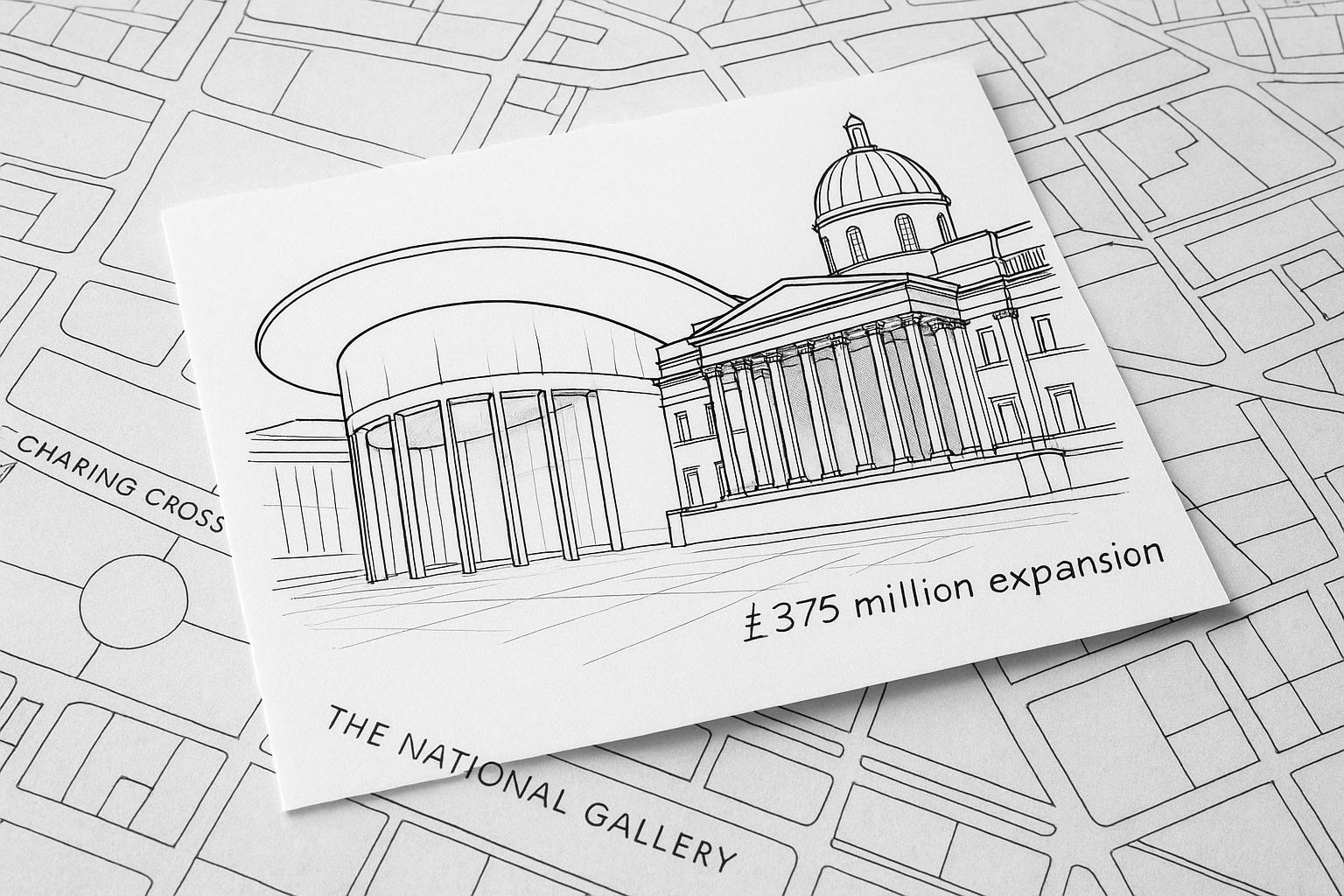

Britain’s art world has recently witnessed a landmark moment with the National Gallery in London unveiling two record-breaking donations, totalling £300 million, which together with an additional £75 million from the National Gallery Trust will fund a bold expansion project. This initiative, named Project Domani, aims to build a new wing that will significantly broaden the gallery’s traditional focus, encompassing modern art from the 20th and 21st centuries for the first time. The funding comes from prominent donors, including the Cardiff-born tech financier Michael Moritz and the Julia and Hans Rausing Trust, marking a transformative step for the gallery amid a competitive and evolving international art landscape.

Historically, the National Gallery’s collection has centred on works preceding 1900, leaving modern and contemporary art largely to institutions like the Tate. As part of this expansion, the gallery plans to replace an existing hotel and office space adjacent to its Trafalgar Square site with a striking new wing. A global architectural competition has been launched to select a fitting design for the project. National Gallery director Gabriele Finaldi described this as one of the gallery’s most ambitious developments, signalling a departure from past practice and an embrace of broader artistic horizons after its bicentenary year.

The Julia Rausing Trust’s £150 million pledge stands as the largest single cash donation ever made to a museum or gallery worldwide. This historic gift, alongside Moritz’s substantial contribution, not only provides financial muscle to the gallery but also signals a new era of collaboration, particularly with the Tate, as the two institutions explore ways to complement their collections rather than compete. This is significant in the context of British art philanthropy, which has tended to lag behind the United States, where museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York or the Getty in California benefit from far larger endowments and a more established culture of mega-giving by billionaires.

The American art market’s financial might has long fostered intense competition among auction houses and galleries, driving record-breaking prices for works by artists such as Mark Rothko, whose pieces have fetched upwards of $186 million. This has made it increasingly difficult for UK institutions to acquire highly sought-after modern artworks, a challenge that the National Gallery now hopes to address through Project Domani. Yet, this shift also raises concerns about the growing rivalry between UK galleries. Previously, a 'non-compete' understanding between former directors of the Tate and National Gallery encouraged specialisation that benefited the public by maintaining a diverse but complementary national collection. Breaking this convention amidst already limited UK resources could be counterproductive.

Michael Moritz himself, a seasoned collector of British modern art including works by Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and Frank Auerbach, underscores the blend of personal influence and public curation entailed in the gallery’s new path. While the gallery has traditionally focused on thematic acquisitions designed to support exhibitions, the infusion of major private collections may reshape curatorial approaches and public expectations. This development illustrates the complex interplay between private wealth and public cultural institutions in shaping national art heritage.

Meanwhile, broader philanthropic activity in the UK arts sector highlights mixed trends. For instance, Goldsmiths, University of London, recently received a valuable £6 million donation comprising cash and a 60-piece art collection from former investment banker Peter L. Kellner. This gift is particularly notable as an unrestricted asset that can support teaching, research, and exhibitions at a challenging time for the university, reflecting the vital role of private donations in sustaining cultural education and access amid financial pressures.

In sum, the National Gallery’s ambitious expansion, backed by unprecedented donations, opens a new chapter for British art institutions. It signals a desire to compete on the global stage with American counterparts while navigating the delicate balance between competition and collaboration at home. How Project Domani will reshape the UK’s cultural landscape remains to be seen, but it undoubtedly reflects evolving patterns of philanthropy, market dynamics, and institutional identity within the art world.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3], [5]

- Paragraph 2 – [2], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [3], [5], [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 5 – [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [6]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [3], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services