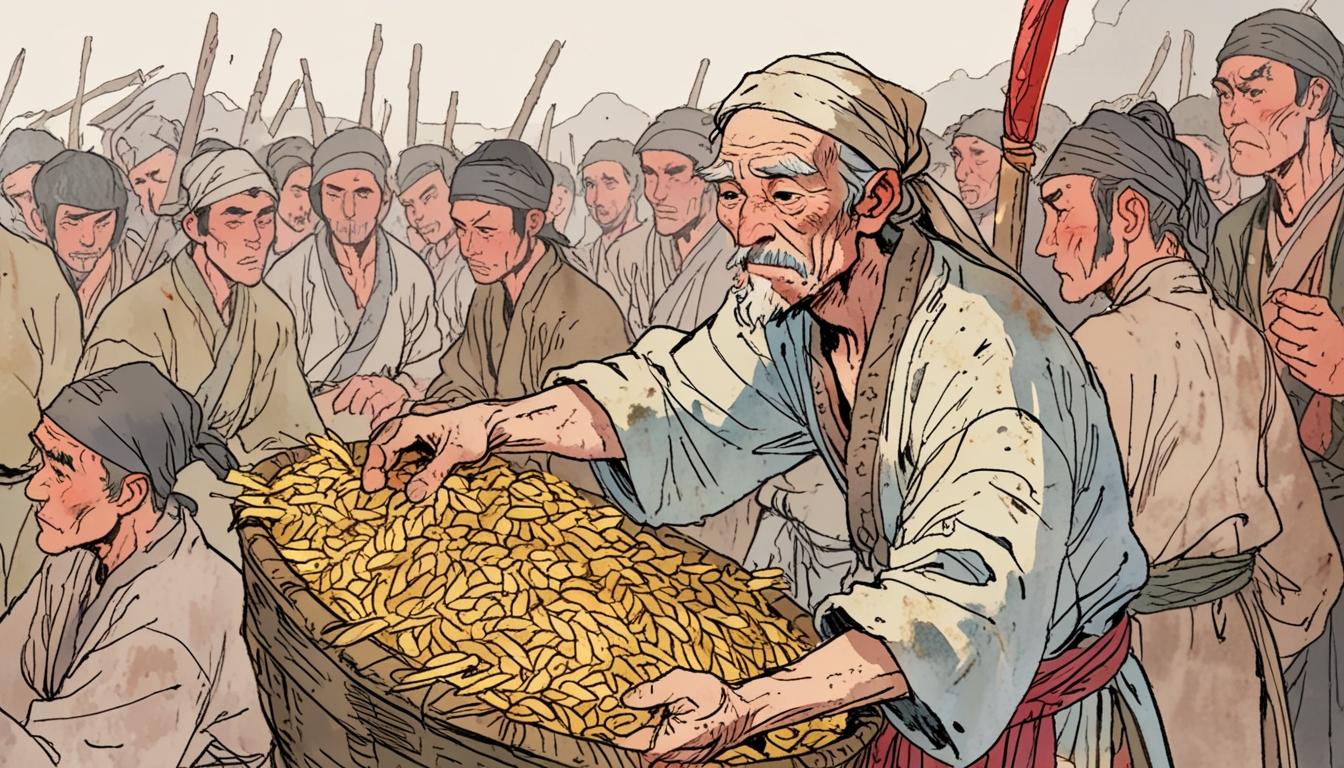

In the summer of 18 CE, China witnessed a notable uprising known as the Red Eyebrows rebellion, where thousands of starving farmers protested against the Han dynasty’s elite over grain hoarding amidst widespread famine. This historical episode, chronicled in the Han Shu (Book of Han), revealed deep-rooted societal inequalities tied to technological advances that, while boosting production, largely benefitted the wealthy and bureaucratic classes at the expense of common peasants.

The Han dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE) was among the most advanced civilisations of its time, paralleling the Roman Empire in development. Innovations such as the iron plough enabled unprecedented agricultural yields, but rather than alleviating poverty among farmers, these advances entrenched agrarian oligarchies and expanded bureaucratic wealth. Officials earned substantially more—up to 30 times—than those working the land. When droughts induced famine, elites maintained their luxurious lifestyles while peasant families suffered severely.

This dynamic—the interplay of technology, inequality, and social structure—has been recurrent throughout history and remains relevant today, particularly amid the present AI-driven technological revolution. The concern about technology exacerbating inequality echoes similar patterns seen in ancient China and other historical contexts.

Research led by Professor Peng Zhou of Cardiff University investigates this issue across 2,000 years of Chinese history, analysing wage inequality relative to technological and institutional changes using detailed dynastic records such as the Book of Han and Tang Huiyao. To compare wages across millennia, salaries paid in various commodities like grain, silk, silver, or services were standardised into a "rice wage" metric reflecting rice's historical economic stability in China.

Zhou and colleagues identified a cyclical pattern in the relationship between technological growth and inequality influenced by four key factors: technology (T), institutions (I), politics (P), and social norms (S). This cycle consistently appeared across dynasties:

Technology spikes growth and inequality: For example, the Han dynasty’s iron-working advances and the Tang dynasty's block printing and steelmaking dramatically increased productivity and empire size. However, these benefits typically accumulated at the top levels of society, widening the wage gap between officials and peasants.

Institutional mechanisms moderate inequality: Institutions like the imperial examination system (Ke Ju) introduced during the Sui dynasty and dominant in the Song dynasty fostered some social mobility, reducing wage disparities. Nevertheless, bureaucracy often bred corruption, favouritism, and bribery that later intensified inequality.

Wars and political turmoil reduce inequality but destabilise society: External conflicts such as the Tang dynasty’s numerous battles drained resources and led to salary cuts and tax hikes. During these periods, inequality fell because all societal layers suffered hardship, but this came with widespread instability, famine, and disintegration of central authority.

Social norms cement hierarchies: The influence of Neo-Confucianism from the Song dynasty onwards emphasised social harmony and hierarchical order, which supported imperial authority but also reinforced elite privileges, sometimes blocking reform and adaptability during crisis periods.

The Qing dynasty, China’s last imperial dynasty, epitomised this cycle. Despite economic growth during the 18th century, inequality soared due to corruption, exemplified by the official Heshen, whose wealth rivalled the empire's annual revenue. As natural disasters, rebellions, and foreign invasions compounded, the Qing state’s failure to reform economically and institutionally led to its eventual collapse.

A comparative view of Britain’s industrial revolution reveals similar patterns over a shorter timescale. Technological advances such as the steam engine concentrated wealth among industrialists while factory workers faced poor conditions and low wages. After decades of inequality, labour movements and reforms like trade union recognition and factory laws emerged to reduce disparities, particularly after the devastations of two world wars, which also helped flatten wealth concentration.

In the United States, rapid technological revolutions—from oil and manufacturing to information technology—have repeatedly amplified inequality. Wealth amassed by industrial magnates like John D. Rockefeller contrasted starkly with workers' stagnant incomes in the early 20th century, culminating in the 1929 Great Depression. Subsequent political reforms under the New Deal and wartime economic changes promoted broader prosperity, but since the 1980s, deregulation and tax policies have again favoured the wealthy, pushing inequality upward.

In the contemporary era of AI and automation, the historic tension between technological progress and inequality persists. AI promises increased productivity but also threatens widespread job displacement and a concentration of power among a few technology firms. As Zhou outlines, the future of AI’s societal impact hinges not simply on the technology but on institutional and political decisions about how its benefits and burdens are distributed.

The emerging political battles over AI governance echo historical struggles over who controls technological wealth and resources. Advocacy groups call for ethical AI use and regulation to protect social equity, mirroring past labour protests against exploitative industrial practices.

Peng Zhou's analysis underscores that while technology remains a powerful driver of economic growth, its effects on inequality depend deeply on the accompanying institutional frameworks and societal values in place. The past warns that unchecked concentration of technological spoils risks deepening inequality, whereas integrated reforms and social movements can balance growth with broader inclusion. This long-term historical perspective offers insight into the complex challenges facing societies in navigating the current and future digital transformations.

Source: Noah Wire Services