There is growing alarm over the state of higher education in the UK, with architecture departments among those hit particularly hard by a crisis that has been long predicted but is now coming into sharp focus. A parliamentary inquiry in 2023 warned that the current funding system for higher education was unsustainable and would trigger significant problems in subsequent years. This prediction has since been borne out, with universities across the country enduring financial strain, dwindling admissions, and rising redundancies, alongside mounting industrial action from staff.

The University and College Union (UCU) has reported that some 5,000 university job losses have already been announced, with fears of a further 5,000 cuts looming due to ongoing budget deficits and a £238 million cut forecast across the sector. In a striking development earlier this year, the UK’s first “super university” was announced—the merger of the University of Greenwich and the University of Kent. Official statements from both institutions stress that the merger was not financially motivated, although Kent’s recent £6.3 million deficit and Greenwich’s ongoing restructuring, which has included redundancies, suggest otherwise to some observers. This move reflects wider survival strategies as universities, apart from a select few top-tier ones, aggressively tighten budgets in response to a funding system described as “broken” by academics and union leaders.

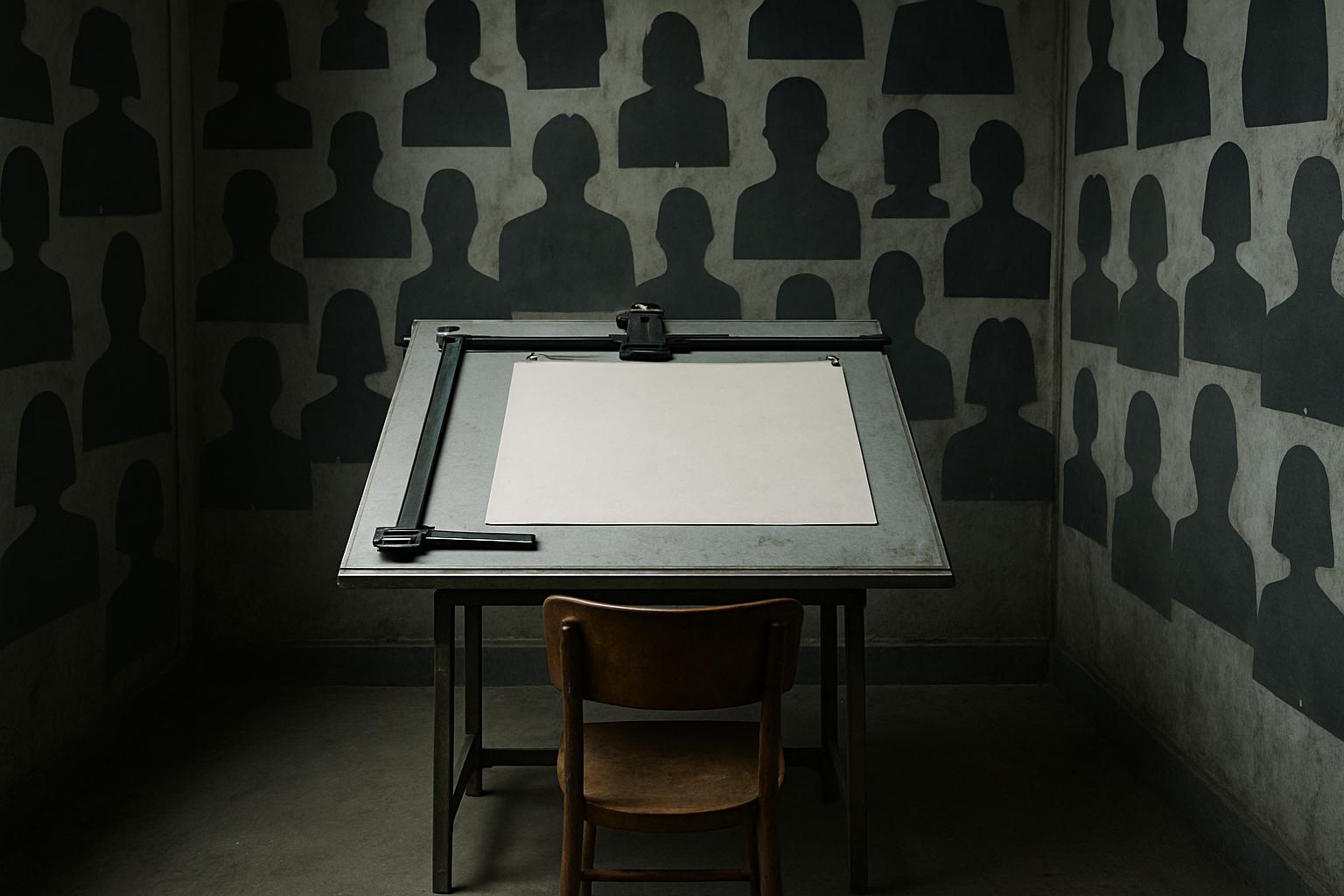

Architecture courses face particular vulnerability in this crisis due to their resource-intensive nature and the necessity for hands-on teaching. Universities including Newcastle, Greenwich, and Sheffield, despite their established reputations, are grappling with threats of cuts and industrial action. Some institutions have temporarily shielded architecture teaching from frontline reductions, but the underlying financial pressures persist, creating a climate of uncertainty and low morale. Laura Mark, a former architecture academic, notes that these courses have already suffered and that more damage is inevitable without systemic change. Matt Perry, chair of the UCU at Newcastle University, highlights how the sector's over-reliance on international students—who pay significantly higher fees—once masked deeper funding problems. With a government clampdown on immigration, international student numbers dipped in 2024, causing universities to reconsider their financial models.

This unsound dependence, combined with a halt in domestic tuition fee growth since 2011 (save for a marginal rise anticipated soon), has squeezed university budgets. Many institutions had geared investments in infrastructure and facilities to the supposed continuing influx of international students, creating a period of artificial prosperity now ending abruptly. Data from the Office for Students confirm that 44% of UK higher education providers operate at a deficit, with numbers worsening since 2021. This precarious financial foundation threatens to destabilise architecture education significantly, as redundancies, course cuts, and strike action disrupt both staff and students.

The challenges extend deeper than mere funding. The sector has seen rapid expansion in accredited architecture programmes in the past decade—from 38 to 63—raising questions about the market's capacity to sustain them all. Furthermore, the prioritisation of research output and swelling administrative costs have shifted focus and resources away from teaching. Alan Jones, professor of practice and education at Queen's University Belfast and former RIBA president, points to these issues as well as a stagnation in international student numbers as contributors to the current crisis. He advocates for innovative solutions like sharing online lecture modules across institutions and suggests government funding adjustments, such as re-categorising architecture alongside engineering to reflect its technical demands, which could unlock an estimated £100 million more annually.

For students, the impact is tangible and increasingly severe. Industrial action has cost universities millions in compensation, with Newcastle University paying nearly £2.5 million to over 10,000 students for missed teaching. Students at Sheffield report missed in-person studio time, fragmented teaching across alternative venues, and anxieties over course discontinuations and the forced reshaping of degree pathways, including the removal of combined architecture and landscaping or engineering master’s options. Some have even been told to avoid planned industry placements to ensure course viability upon their return. Greenwich students describe a chaotic and opaque restructuring process, with senior staff suspensions reflecting internal turmoil. Amid these upheavals, the ongoing merger between Greenwich and Kent has been conducted with little transparency, exacerbating staff unease.

Nonetheless, the impact is not uniformly bleak. The University of Kent reports record undergraduate numbers for architecture and describes itself as “doing well” despite broader financial challenges. The University of Manchester’s architecture department similarly remains robust and healthy. However, the overall picture remains strained, with job losses, course closures, and funding shortfalls persisting sector-wide. Universities like Sheffield have substantial deficits—£50 million due to enrolment drops and reliance on international student fees—forcing cuts and financial reviews.

The UK's higher education crisis is a multifaceted problem requiring urgent attention. Industry bodies and unions continue to press the government for funding reform and regulatory improvement, a sentiment echoed in a 2023 House of Lords report that criticised the Office for Students and the government for their failure to avert the sector’s decline. Until these underlying issues are remedied, architecture courses and the future professionals they educate will remain at significant risk, caught in the crossfire of a system undergoing painful adjustment.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3], [5]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [3], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [4], [7]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [3], [6]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [3], [5], [6]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [4], [7]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [2], [3]

Source: Noah Wire Services