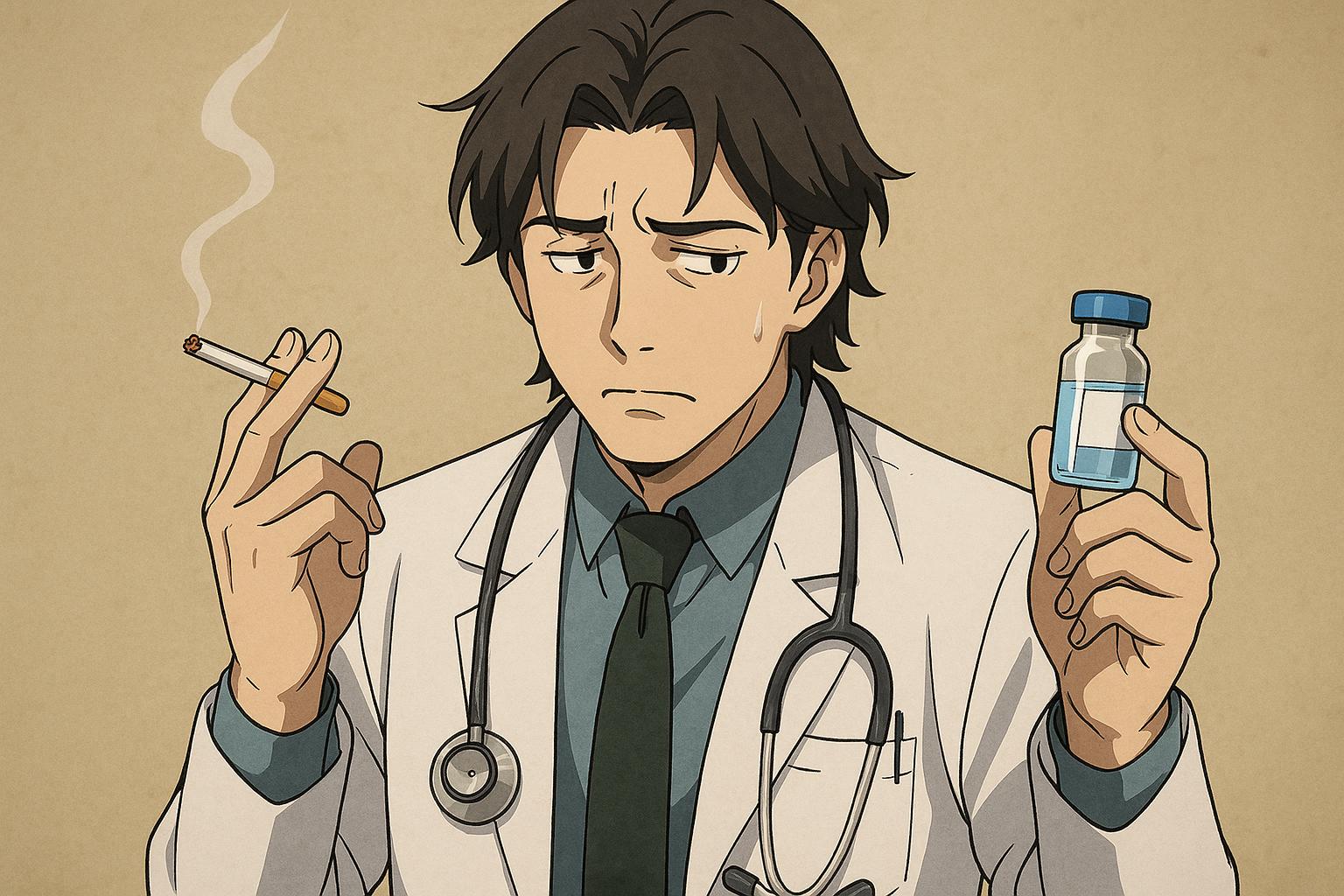

The recent influx of investment from tobacco companies into medical research is stirring significant concern among healthcare professionals and health advocates. While the initiative may seem promising at first glance, as it is framed as an attempt to treat illnesses that their products have long exacerbated, the historical and ethical implications paint a far more troubling picture.

Philip Morris International (PMI) is at the forefront of this trend, having invested billions into the pharmaceutical sector, particularly in treatments for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases caused by smoking. The paradox is stark: the very entities responsible for the proliferation of these illnesses are now positioning themselves as potential healers. PMI, which sells approximately a quarter of the world’s cigarettes—including the notorious Marlboro brand—has made headlines for its substantial financial engagement in companies developing drugs to combat conditions such as lung cancer, heart disease, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The irony is palpable. Eric Lawson, the actor who famously portrayed the Marlboro man in advertisements and had been a long-time smoker, succumbed to COPD, illustrating the human cost of tobacco-related illnesses. In the UK, tobacco remains the leading cause of lung disease, contributing to an annual financial burden of £2.5 billion for the National Health Service (NHS).

Laura Williamson, policy manager at Asthma + Lung UK, captured the sentiments of many when she expressed her disapproval, stating, "There is a huge issue about tobacco companies taking two bites of the cherry here." Critics argue that allowing tobacco companies to profit from the illnesses they have fostered is morally reprehensible. They assert that these companies are not genuinely invested in public health; were this the case, they would cease selling cigarettes outright.

Concerns were further amplified following PMI's contentious acquisition of Vectura, a company focused on developing inhalable therapies for asthma and COPD. The backlash from health professionals and organisations—including the British Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society—was swift and severe, leading to significant restrictions on Vectura’s research partnerships. These organisations urged universities to bar any collaborations with tobacco companies, fearing that such ties could undermine the integrity of scientific research. Ultimately, PMI was compelled to divest Vectura for £150 million, a sharp decline from its initial purchase price of over £1 billion.

Despite the sale, PMI has clarified its commitment to respiratory health. A spokesperson emphasised that while the company sold off specific segments of Vectura, it continues to develop inhaled therapies separately. Additionally, the company acquired OtiTopic in 2021, a firm working on inhalable treatments for heart attacks, further demonstrating its ongoing ambition in the healthcare space.

Other tobacco giants are similarly diversifying. Japan Tobacco International has branched into pharmaceuticals targeting lung cancer and heart disease, while British American Tobacco invests in vaccine development for respiratory illnesses, including Covid-19. The US’s Altria Group is exploring partnerships focused on innovative drug delivery methods for weight management drugs, effectively embedding itself deeper into the pharmaceutical landscape.

Yet, these ventures are met with scepticism. Critics warn that allowing tobacco companies into the medical sphere compromises the sanctity of scientific research. Williamson asserts that such entanglements erode public trust, emphasising that the involvement of the tobacco industry in reputable research mediums can muddle the narrative around smoking's harms. Research from the Tobacco Control Research Group highlights a troubling history: tobacco companies have previously financed studies to downplay the detrimental effects of their products, sowing doubt in public health discourse.

Nicholas Hopkinson, a professor of respiratory medicine at Imperial College London, starkly characterised tobacco companies' moves into healthcare as an affront to ethics. He stated, “The idea that these companies should be allowed to take this blood money and launder their reputation by diversifying into healthcare is simply obscene.”

In an ironic twist, tobacco companies profess that their entries into the healthcare market are genuine efforts to transition away from cigarettes. PMI reported that as of October 2024, 38% of its revenue came from smoke-free products, with ambitions to increase that to two-thirds by 2030. Such claims, however, are met with scrutiny from health advocates who remain sceptical about their true intentions.

The convergence of the tobacco and pharmaceutical industries is a complex and contentious one. As tobacco companies step deeper into health-related ventures, the potential for profit clashes with ethical responsibilities, raising profound questions about the integrity of public health efforts and the accountability of those who have historically perpetuated harm. The fear lingers: will these companies genuinely prioritise health and well-being, or will they continue to profit from the very illnesses they have championed through their products?

Reference Map

- Paragraphs 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10: 1

- Paragraphs 3, 7: 2, 3

- Paragraphs 6: 4, 5, 6

- Paragraphs 11, 12, 13: 7

Source: Noah Wire Services