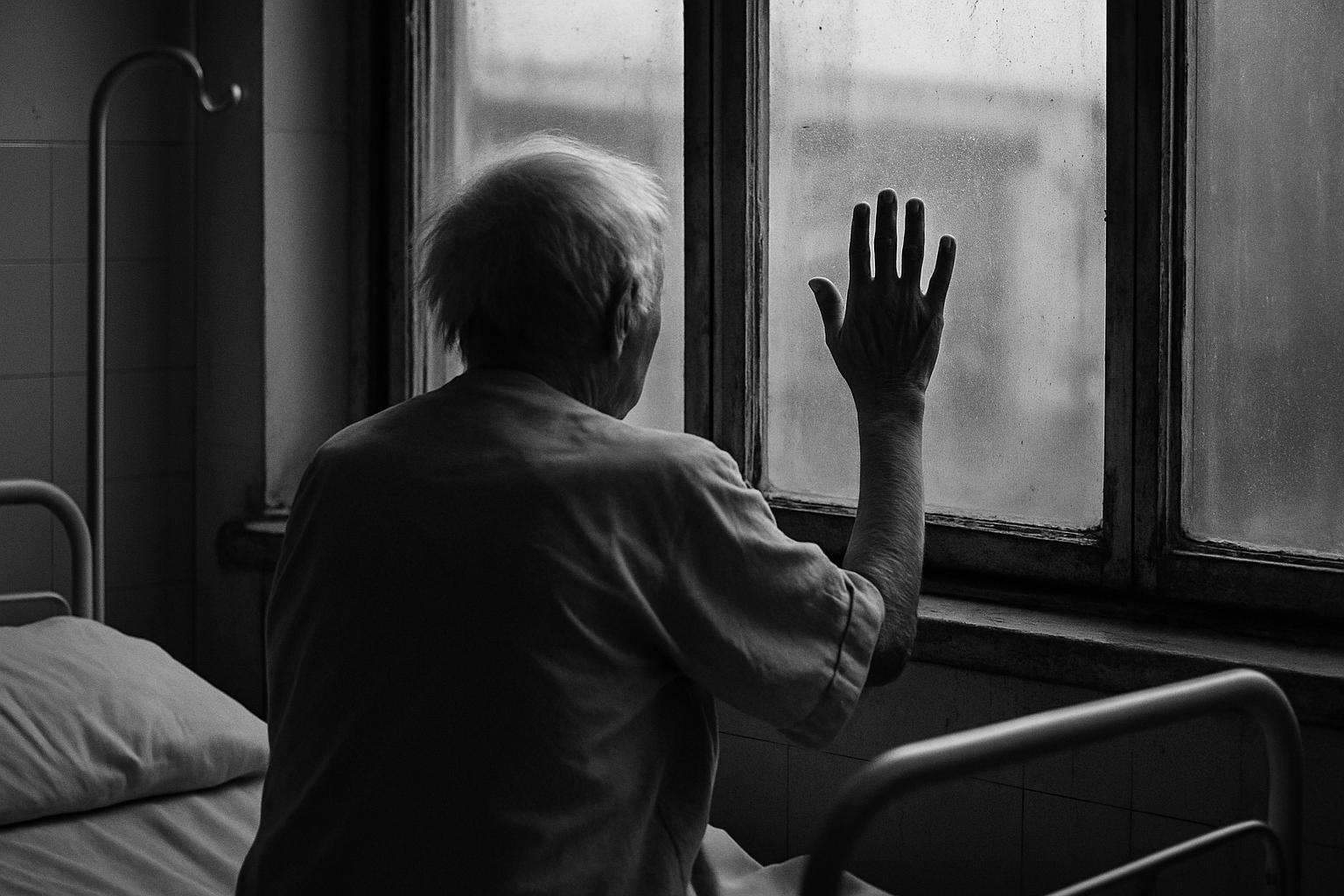

On a typical medical ward for older adults, the stark contrast between varying degrees of caregiving and social support becomes dramatically apparent. Among patients over 75, medical teams often differentiate between the "young old" and the "old old," a division that guides the assessment of their complex physical, cognitive, and social needs. Issues commonly encountered include heart failure, chronic lung diseases, diabetes, cognitive decline, frailty, and frequent falls. Yet beyond the clinical picture, it is the patients' social circumstances—living arrangements, availability of home help, and frequency of social contact—that profoundly shape their hospital experience and recovery prospects.

In one revealing round, many elderly patients are isolated, with few or no visitors even over a weekend. Loneliness is palpable: patients long for simple companionship or help with everyday tasks such as foot rubs or toenail trimming. One elderly gentleman, despite severe respiratory disease, is visibly uplifted by the presence of his three sons, who provide emotional support and nutritious meals, highlighting that family presence can be the most potent intervention. This scene, striking in its warmth amid otherwise somber surroundings, underscores how essential physical and moral support are in patient outcomes.

The absence of visitors in many cases is often attributed by healthcare staff to societal pressures such as adult children’s work commitments, caregiving for other family members, and personal challenges including conflict or emotional exhaustion. Nonetheless, medical professionals acknowledge that loneliness in elderly patients intensifies illness severity and prolongs recovery, a condition not remediable by medication alone. This resonates with cultural traditions that emphasise filial care, where family roles in eldercare are clearly defined, yet modern life complicates these responsibilities. Caregiving today often demands significant sacrifices, with flexibility and economic privilege influencing who can provide consistent support.

Research reinforces the gravity of this issue. Studies reveal that caregivers of older adults frequently experience social isolation and loneliness themselves, with about 12% isolated and 27% lonely. Spousal caregivers, those providing intense care, and those caring for relatives with dementia or in healthcare institutions report particularly high levels of loneliness and stress. Moreover, caregivers' health and social wellbeing are at risk, with factors such as being unmarried, male, or in poor health exacerbating isolation. Interventions tailored to caregivers’ needs, including online social support programs, are advocated to help mitigate these adverse effects.

Loneliness in older adults and their caregivers is not just an emotional state but a public health concern linked to increased risks of premature death, dementia, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke. Nearly one-third of adults aged 45 and older report feeling lonely, while about a quarter of those over 65 are socially isolated. Loneliness also correlates with functional decline and higher healthcare costs due to increased disability. Longitudinal studies prior to and during the recent pandemic highlight that loneliness may worsen over time, especially among former caregivers and those facing financial strain or poor health, signalling the urgency for targeted social and health policy interventions.

The poignant reality faced daily in hospital wards—that many elderly patients endure not just physical illness but the heavy toll of loneliness—calls for a renewed societal focus on caregiving. While improved social policies may help alleviate systemic barriers, they cannot replace the individual acts of commitment and presence that embody meaningful care. Bearing witness to the vulnerabilities of ageing and prioritising connection might be among the greatest acts of love, potentially improving outcomes where medical treatment alone falls short.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 2 – [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [2], [3], [4]

- Paragraph 5 – [5], [7], [6]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [5], [6], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services