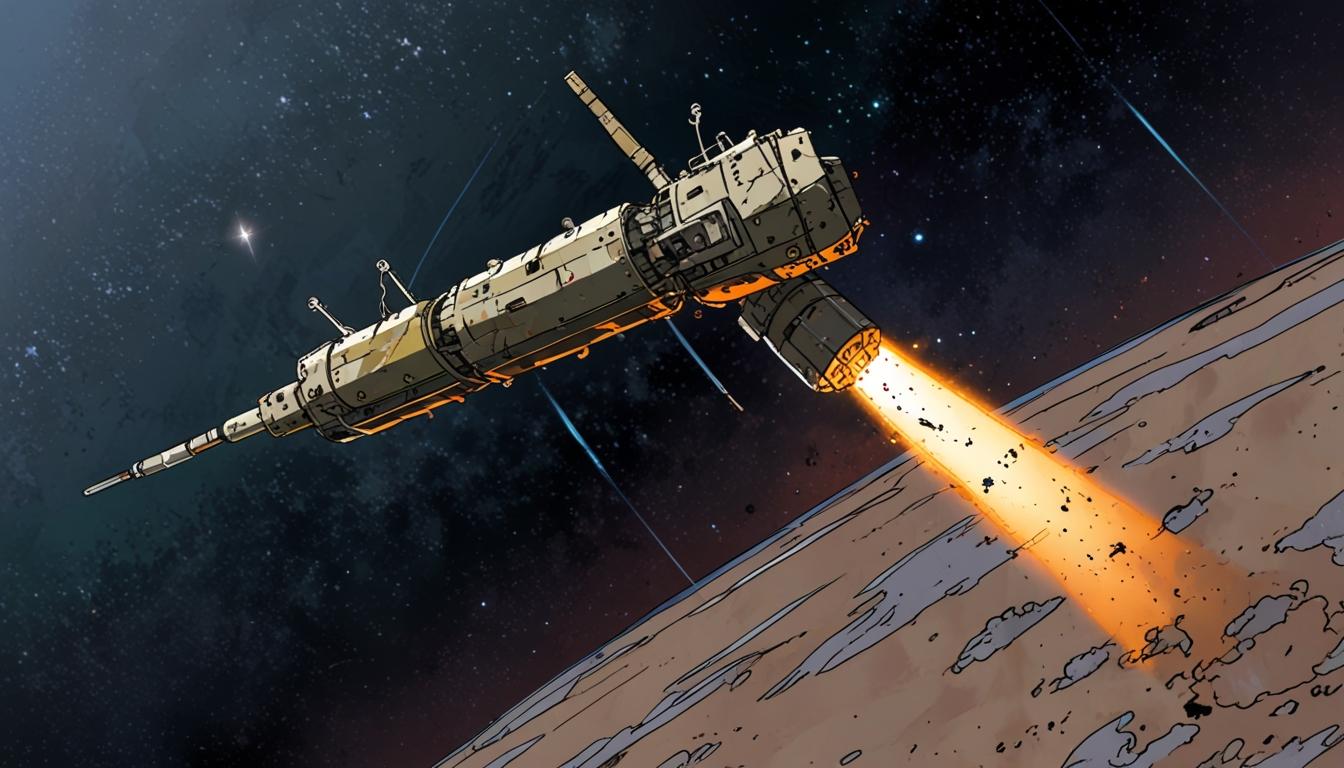

In recent developments concerning orbital security, Russia’s prototype anti-satellite weapon, launched in 2022, has reportedly lost control and begun tumbling uncontrollably in orbit, indicating it is no longer functional. This information comes from commercial space situational awareness (SSA) companies that have been tracking the spacecraft. Known as Cosmos 2553, the vessel is believed to be part of Russia’s efforts to develop a nuclear-capable space weapon designed to disable multiple satellites simultaneously in low Earth orbit (LEO). Such a weapon poses a significant threat to proliferated satellite constellations, which ordinarily could withstand the loss of a few individual spacecraft.

Officials from the commercial firm LeoLabs shared with Payloadspace.com that their radar systems detected the unusually dense Cosmos 2553 drifting out of control in November 2023. This abnormal density suggests the presence of a dummy nuclear payload aboard the craft. Maxar Technologies later confirmed these observations with satellite imagery. The news was initially reported by Reuters.

Alongside these developments, two recent reports from the Secure World Foundation and the Center for Security and International Studies (CSIS) detail the intensifying threats to orbital assets amid increasing military competition in space, particularly between the United States and China.

The reports highlight the surge in rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO) missions by various countries. These missions involve spacecraft approaching satellites for purposes ranging from servicing and intelligence gathering to potential aggressive action, whether kinetic, electronic, or energetic.

For instance, Russia’s Luch 2 satellite conducted close approaches to communications satellites owned by US and European companies both in July 2024 and earlier in January. China similarly demonstrated aggressive RPO techniques last year, with five satellites involved in a high-intensity campaign that included simultaneous proximity events occurring within meters of their targets. The US has also been active in RPO operations, with numerous missions in recent years. One notable example is the LDPE 3A satellite, which positioned itself near an experimental Chinese spacecraft that released an unidentified object, possibly a spent motor, in January 2024. This month, the head of the US Space Command emphasised the necessity for “orbital interceptors” to secure a strategic advantage in potential space conflicts.

In addition to direct satellite activities, electronic interference in space operations is increasing. The problem of GPS jamming, once relatively limited, is now widespread across around 20 countries. Nations such as Russia, North Korea, and Israel have been identified as sources of this interference. Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation commented on the issue, noting that airline pilots have begun noticing GPS jamming incidents, particularly when their onboard clocks suddenly run backwards, signalling clock disruptions. This ongoing disruption has prompted calls for enhancements in GPS security and has encouraged other countries and private entities to develop alternative secure positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) solutions.

With commercial spacecraft playing an ever more critical role in communications and military targeting, experts warn these assets are increasingly viewed as legitimate military targets. Clayton Swope, deputy director of CSIS's Aerospace Security Project, remarked recently that “the writing is on the wall here that those commercial assets will be treated as military targets by US adversaries.” This evolving threat landscape puts further emphasis on the need for robust defence and strategic planning for space-based infrastructure.

These reports and observations collectively underscore the growing complexity and heightened risks of space operations. The combination of technological advancements, military ambitions, and electronic warfare tactics marks a significant escalation in the strategic and security environment of Earth’s orbital domain.

Source: Noah Wire Services