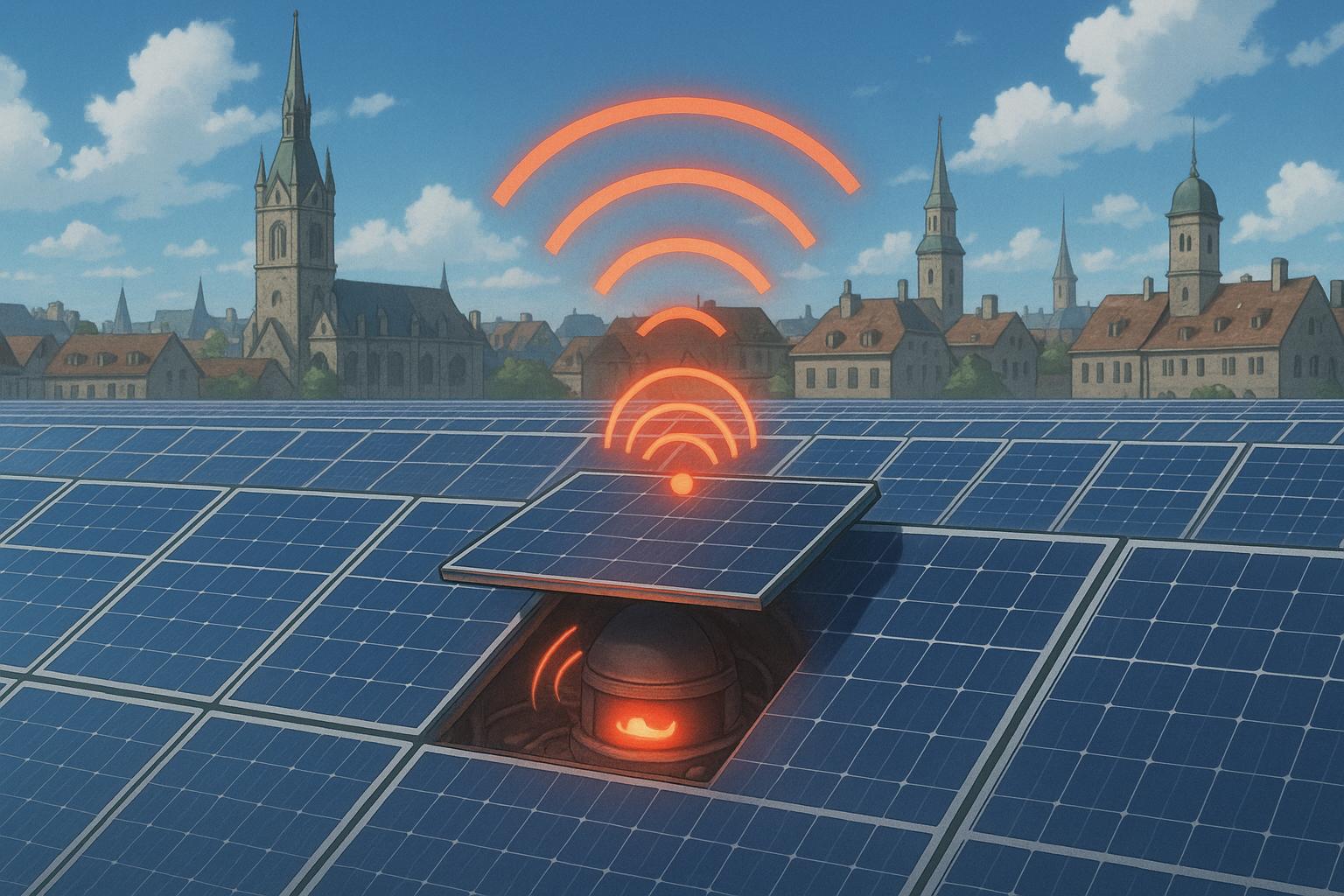

The recent discovery of hidden remote access devices in solar power infrastructure has raised significant concerns across Europe regarding the potential vulnerabilities of its power grids. The revelation, which emerged following a review of Chinese-made inverters used in American solar farms, has alarmed officials in light of a major blackout that affected millions in the Iberian Peninsula. As the world increasingly turns to renewable energy, these findings cast a shadow over the reliability and safety of solar installations, particularly those reliant on Chinese technology.

Chinese manufacturers dominate the global market for solar inverters, with an astonishing 78% of the inverters in Europe originating from firms such as Huawei and Sungrow. This concentration of supply—from companies linked to the Chinese government—raises alarm about the implications for energy sovereignty in the West. The embedded communication devices were reportedly concealed in technical schematics, suggesting potential malintent to undermine grid stability remotely. Concerns are not merely hypothetical; they echo previous incidents where solar inverters in multiple countries were altered from afar, highlighting operational vulnerabilities that could enable widespread power disruptions.

The European Solar Manufacturing Council echoes these apprehensions, stating, “Europe’s energy sovereignty is at serious risk due to the unregulated and remote control capabilities of photovoltaic inverters from high-risk, non-European manufacturers.” This growing dependency on foreign technology stands in stark contrast to the continent's pronounced push for energy independence, particularly after the geopolitical upheaval caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which exposed Europe's over-reliance on external energy sources.

Simultaneously, the past year has seen a sizeable spike in electricity generation from solar panels, amounting to almost 68 terawatt hours in the first quarter of 2025 alone, a notable increase of nearly a third compared to the previous year. This uptick underscores the pivotal role solar energy plays in both the renewable portfolio and overall energy supply within Europe, where forecasts suggest an installed photovoltaic capacity exceeding 800 gigawatts by 2030. However, this ambitious roadmap is overshadowed by the technical risks posed by unregulated technologies.

Countries like Lithuania have begun taking proactive measures, enacting legislation to prohibit the use of Chinese-manufactured inverters in significant photovoltaic projects. This initiative reflects a growing recognition among European nations of the need to stabilise their energy infrastructure against potential external threats. Other countries, including Estonia and the UK, have similarly initiated assessments and responses to the risks associated with foreign technology in their energy landscapes, marking a shift in operational caution and regulatory intent.

Recent developments have prompted increased scrutiny in the European Parliament, where lawmakers are contemplating stricter controls for solar inverters to mitigate security risks. The implementation of the NIS2 directive, aimed at enhancing cybersecurity across critical infrastructure sectors, represents a significant first step, although critics argue it narrowly focuses on larger projects, leaving smaller installations susceptible to cybersecurity threats.

As the push for renewable energy continues, the juxtaposition of growing energy needs against the backdrop of technological vulnerability presents a complex challenge for European policymakers. With the integration of solar energy in the region becoming ever more vital to meet climate goals, ensuring the integrity and security of these systems from foreign influence remains paramount. The delicate balance between fostering an expansive green energy market and safeguarding technological integrity will determine how effectively Europe can navigate this landscape of dependency.

To secure its energy future, Europe must not only advance its renewable ambitions but also prioritise cyber resiliency and national sovereignty, particularly in areas interlinked with foreign technology. The task ahead is to cultivate a self-sufficient energy infrastructure that can withstand geopolitical pressures, thereby ensuring the lights remain on without the potential hazards of reliance on foreign entities.

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 3 – [3], [4], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 5 – [5], [6]

- Paragraph 6 – [3]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [4]

Source: Noah Wire Services