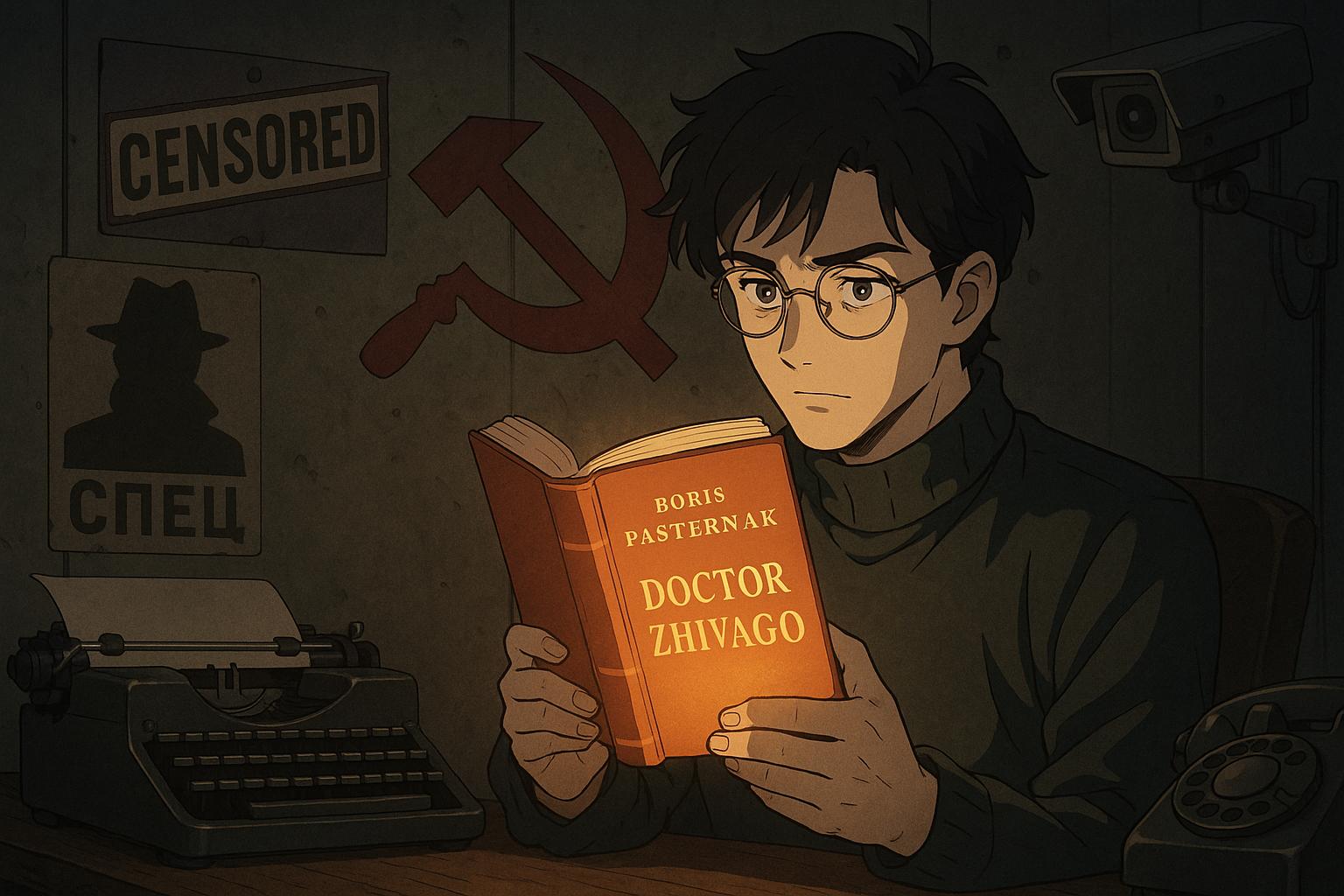

Boris Pasternak, a name synonymous with literary defiance, turned his back on conformity in favour of a fragile individualism that resonated deeply during one of history's most oppressive periods. His novel, Doctor Zhivago, while a complex tapestry of human emotion and experience, was hijacked into the ideological battleground of the Cold War. The story of its dissemination—a tale of courage, collaboration, and covert operations—reflects not only Pasternak's fight against censorship but also illustrates how literature can be wielded as a weapon in the service of propaganda.

The journey of Doctor Zhivago began with Pasternak’s trepidations about publication, haunted by the fates of fellow writers like Andrei Platonov and Evgeny Zamyatin, who had faced grim punishments for their words. Ultimately, through Italian literary agent Sergio D’Angelo, Pasternak placed his fate—and that of his oeuvre—into the hands of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the publisher who would bravely release the novel in Italian in 1957. Aware of the threats from both the Italian Communist Party and the Soviet authorities, Feltrinelli’s commitment to publish an uncensored version made waves that spread far beyond Italy.

When Soviet officials rejected Doctor Zhivago, branding it as an "estrangement from Soviet life," the CIA quickly spotted its potential for sowing discord within the Soviet Union. Declassified documents later revealed how the agency recognised that the novel’s absence in Pasternak's homeland starkly highlighted the oppressive nature of Soviet censorship. This perspective became a cornerstone of their psychological warfare strategy: by distributing the book widely, the CIA sought to empower individual thought and spark dissent among Soviet citizens who found themselves cocooned in a regime that cloistered critical literature behind walls of repression.

The covert operation to circulate Doctor Zhivago was nothing short of extraordinary. Initially, the CIA relied on espionage techniques; key individuals within MI6 photographed the manuscript on rolls of film to ensure the text reached them securely. In a bold move, miniature editions were smuggled into the Soviet Union, especially during significant international gatherings, such as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair. Young Soviets were showered with these clandestine gifts, ultimately igniting curiosity among those subjected to state-sanctioned information control.

Pasternak’s narrative is intricately woven within the tumultuous backdrop of the Russian Revolution, World War I, and the stark realities of Stalinist rule. His protagonist, Yuri Zhivago, serves as a microcosm of the existential struggle against an oppressive regime, embodying the conflict between personal desires and political mandates. Yet, Doctor Zhivago transcends mere political commentary; it is a reflection of the human condition, exploring love, fate, and the inexorable passage of time. Pasternak's portrayal of the revolution is not one-dimensional; it shows a nuanced progression from initial embrace to profound disillusionment that mirrors the author's own experiences.

Despite its political implications, Doctor Zhivago is frequently overshadowed by the narratives woven around the conflict it ignited. While critics have often tried to pigeonhole the text as solely anti-Soviet, its philosophical inquiries into humanism and individualism resonate beyond such confines. This duality underscores a broader dilemma: must literature engage purely with the political landscape to be deemed impactful? Through Pasternak's lens, we are compelled to confront the value of literature as both a political artifact and a profound artistic endeavour.

The irony of Pasternak’s situation cannot be ignored. Despite the acclaim that followed the book's release, including his winning of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958—which he was forced to decline—he remained a victim of the machinations of both the Soviet regime and the CIA's propaganda efforts. His portrayal as a dissident was complicated; while his works reflected disdain for his government's oppressive policies, he did not define himself solely by opposition. A deeper exploration of his motivations and the context surrounding his work reveals a multifaceted individual poised between art and ideology.

In considering Doctor Zhivago's legacy, Pasternak emerges not merely as a participant in a literary conflict but as a courageous advocate for individual expression. His persistence against the odds helped carve pathways for future generations of authors to voice their truths. Ultimately, Pasternak's fight against censorship serves as a reminder that literature can be both a refuge and a battleground—a paradoxical realm where words possess the power to challenge, transform, and endure in the face of tyranny.

As Edward Bulwer-Lytton once wrote, “Beneath the rule of men entirely great, the pen is mightier than the sword.” In arguing for the autonomy of thought and expression, Pasternak became a symbol of the struggle not just against a totalitarian regime but for the unquenchable fire of human creativity. His story urges us not to overlook the profound nature of literature—an exploration of the depths of the human spirit amidst the trials of an ever-complex world.

Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [2], [3]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 5 – [3], [6]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [2], [4]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services