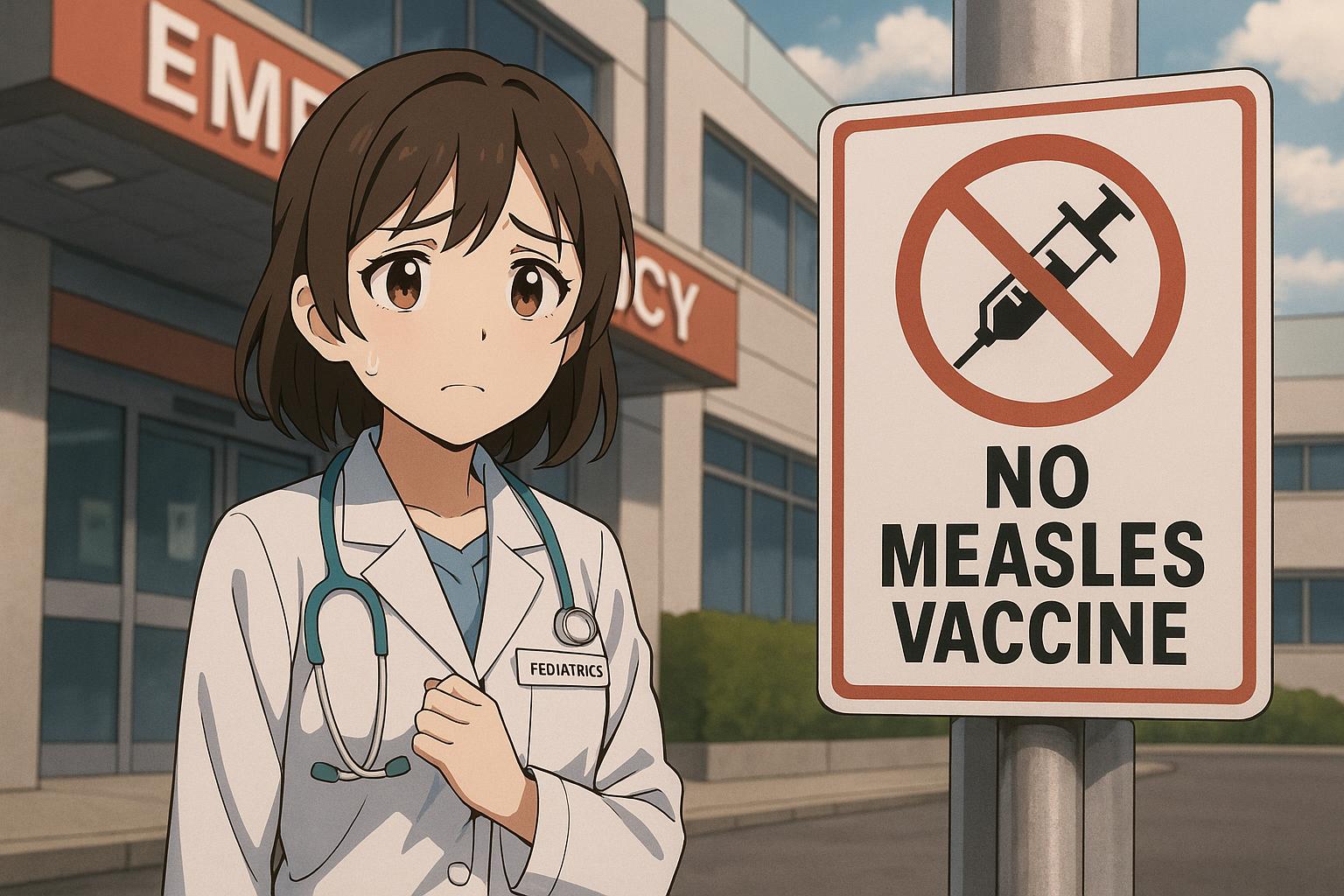

Outside the emergency room of St Thomas Elgin General Hospital, approximately 200 km (125 miles) south-west of Toronto, a stark sign commands attention: “NO MEASLES VAX & FEVER COUGH RASH – STOP – DO NOT ENTER!” The sight of such a warning in the 21st century, in a country that achieved “elimination status” for measles back in 1998, marks a troubling return to a health crisis previously thought vanquished. Canada now stands on the brink of losing that hard-won milestone, primarily due to a significant outbreak of the highly contagious virus in south-western Ontario.

Since October, Ontario has reported a staggering 2,009 cases of measles, a figure that surpasses all cases recorded in the United States combined in 2025 and labels the province as the measles epicentre of the western hemisphere. The tally has surged alarmingly, with hundreds of new cases emerging in just the past month; three-quarters of those afflicted are unvaccinated children, according to Public Health Ontario. The outbreak has already claimed its first victim: a premature infant infected in utero by an unvaccinated mother, with health officials confirming that measles may have exacerbated the baby's other health complications.

Dr. Asmaa Hussain, head of paediatrics at the local hospital, noted, “We have not had a measles outbreak in the community of this size for as long as I have practiced. Lots of doctors have never seen measles before now.” She expressed concern that the actual number of cases might be even higher due to many families opting for home care rather than seeking hospital treatment.

Almost 40% of cases have been reported by the Southwestern Public Health Unit, which serves regions in Oxford county, Elgin county, and St Thomas. The scale of this outbreak, shocking as it may seem, has been perceived as predictable by frontline doctors and public health experts. Factors contributing to the crisis include outdated public health vaccination strategies, reduced access to family doctors, postponed routine immunisations because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a spike in vaccine hesitancy fuelled by misinformation online.

South-western Ontario is home to several close-knit, vaccine-hesitant religious communities, including some Mennonites, who are less likely to engage with public health messaging. The outbreak is believed to have stemmed from a Mennonite wedding in New Brunswick, from which the virus spread into Ontario. This multifaceted situation is echoed by reports of increasing measles cases in Alberta, where the province recorded 710 confirmed cases, marking the worst year since 1986.

Measles presents serious health complications; it is known to cause pneumonia, brain swelling, and even death. Highly preventable through vaccination, it thrives in communities that fall below the herd immunity threshold, which is typically set at 95% for the general population. Unfortunately, Canada’s measles vaccination rates have dropped from 90% in 2019 to 83% in 2023, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Dr. Hussain reported an unsettling trend: many infants under 12 months—who are ineligible for the vaccine—are now contracting measles from older siblings who are also unvaccinated. One infant was reported to have contracted the virus from their mother, who had caught it from her unvaccinated children. Interestingly, while it is illegal to send an unvaccinated child to school in Ontario without specific exemptions, these hesitancies pose a significant challenge in public health discussions.

Immunologist Dawn Bowdish from McMaster University highlighted an additional complication: roughly 20% of Canadians lack a family doctor, and many others have limited access to healthcare. Consequently, parents find it difficult to receive trustworthy guidance about vaccinations. Furthermore, the ease with which vaccine exemptions can be obtained exacerbates the situation, as individuals may leverage loopholes based on vague personal beliefs rather than solid medical or religious grounds.

As extensive efforts ramp up to counteract this outbreak, including the creation of vaccination clinics in south-western Ontario, the government faces substantial difficulties in persuading vaccine-hesitant populations. Public health strategies traditionally emphasising factual information have lost efficacy, necessitating a revaluation of communication methods with these communities—particularly given the heightened anxiety surrounding governmental trust since the pandemic.

Kumanan Wilson, a public health policy expert, underscored the need for authorities to adapt their strategies in communicating health risks. “They’re going to have to learn to navigate this new world of people not trusting government as much and more populist tendencies,” he remarked. Indeed, a recent Angus Reid Institute study indicated that a quarter of Canadians do not trust their provincial governments to manage the outbreak effectively, a figure rising to 27% in Ontario. Alarmingly, one in five Canadians with children under 18 express hesitancy towards vaccination.

Dr. Hussain expressed a growing concern: the current outbreak may not be the last. “My worry is about the next outbreak. Because there will be a next one coming, right?” she said, fearing that other previously controlled diseases could also resurge amid this evolving public health crisis.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3], [4]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [5], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2], [5]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [3], [6]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [2], [6]

- Paragraph 8 – [2], [3], [5]

- Paragraph 9 – [1], [4], [7]

- Paragraph 10 – [1], [3], [4]

- Paragraph 11 – [1], [2], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services