Labour ministers have been accused of muzzling senior military figures after an RAF officer publicly warned that Britain’s air defences could be overwhelmed in a simulation of a Russia‑style attack. The Mail on Sunday reported that Air Commodore Blythe Crawford told a Royal United Services Institute conference in April that a war‑game modelling the opening day of the invasion of Ukraine produced a bleak outcome for UK bases, aircraft and runways — a disclosure that critics say prompted tighter controls on what uniformed officers and officials may say in public. According to RUSI’s conference listing, Crawford took part in the event as Commandant of the RAF’s Air and Space Warfare Centre. (Paragraph 1)

The scenario described by Crawford — run in a synthetic environment known in reporting as ‘Gladiator’ — modelled massed missile, drone and strike‑aircraft attacks on forward air bases and home stations and highlighted shortages of hardened shelters and other resilience measures. Commentators seized on the simulation’s findings as a wake‑up call: the exercise underlined how the concentration of assets and fewer available airfields can leave national airpower vulnerable to coordinated long‑range strikes. These assessments have fed into a wider debate about whether the UK can still assume geographic safety on the western edge of Europe. (Paragraph 2)

RUSI and defence commentators say exercises of this kind are designed to stress test plans and expose hard lessons; but the publicity surrounding the findings appears to have prompted changes to how officials are allowed to speak. The Mail on Sunday reported that organisers alerted attendees at a subsequent land warfare conference to a late change in reporting rules that placed many speeches and panels off the record, and that a reminder has been circulated to officers due to attend next month’s Defence, Security and Equipment International show. RUSI’s own programme confirms it regularly hosts classified and open sessions where sensitive capability and resilience issues are discussed. (Paragraph 3)

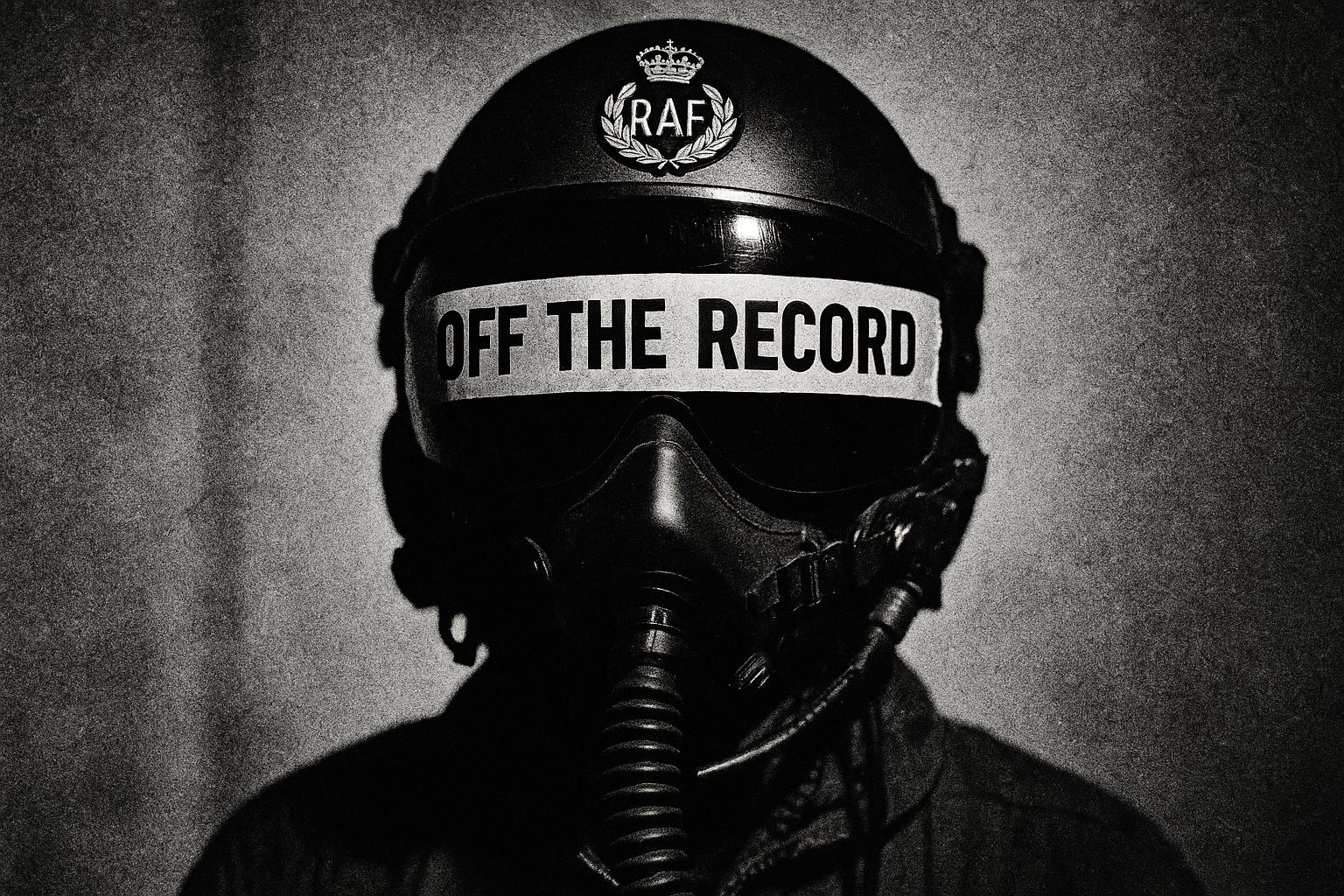

There is a formal framework that governs such contacts with the media. The Ministry of Defence’s Defence Instruction on contact with the media, issued in February 2025, requires authorisation for personnel to speak publicly on defence matters and sets out that senior officers (1‑star rank and above) normally need Directorate of Defence Communications approval — usually with 14 days’ notice — before media contact. The guidance explains these processes are intended to protect operational security and ensure coherent public messaging, a point that officials cite when defending restrictions. (Paragraph 4)

Critics say the effect has been a centralisation of control in No 10’s communications machine. The Guardian reported that new Downing Street guidance has effectively curtailed civil‑service participation at events where journalists are present, prompting think‑tanks and public servants to denounce the approach as heavy‑handed “control‑freakery”. Political blogs and opposition sources have amplified insider accounts suggesting micromanagement, and parliamentary questions from MPs such as Mark Francois have pressed the government for clarity. Those sources characterise the recent pattern of restrictions as politically driven, triggered in part by the embarrassment caused when senior military figures’ public comments diverged from ministerial messages. (Paragraph 5)

Downing Street and the Ministry of Defence have pushed back. A government source told the Mail on Sunday there is no blanket “gag” on public speaking and that arrangements are considered on a case‑by‑case basis, adding that similar procedures have been in place under governments of different parties. The MoD’s public guidance, meanwhile, frames the rules as administrative safeguards rather than a political clampdown. (Paragraph 6)

The row pits two legitimate priorities against each other. On one hand, senior officers and subject‑matter experts argue that transparent public discussion of vulnerability and resilience helps drive corrective investment and public understanding; on the other, ministers and communications officials emphasise the risk that detailed public commentary about specific weaknesses could be exploited by potential adversaries. Tory defence spokespeople have used the episode to argue the ministry is in disarray, while proponents of the tighter rules say disciplined messaging is necessary in a complex security environment. (Paragraph 7)

Whatever the merits of the arguments, the episode has crystallised a broader question about who should set the boundaries of public debate on defence: the uniformed professionals who run exercises and expose shortfalls, or the political leadership that must weigh operational security, diplomatic consequence and public reassurance. The competing accounts — candid war‑game disclosures from officers, official rulebooks on authorised contact, and political accusations of micromanagement — together illustrate why the governance of defence communications remains politically fraught and operationally consequential. (Paragraph 8)

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [4], [3]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 4 – [5]

- Paragraph 5 – [6], [7], [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [5]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [7], [5]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [4], [5], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services