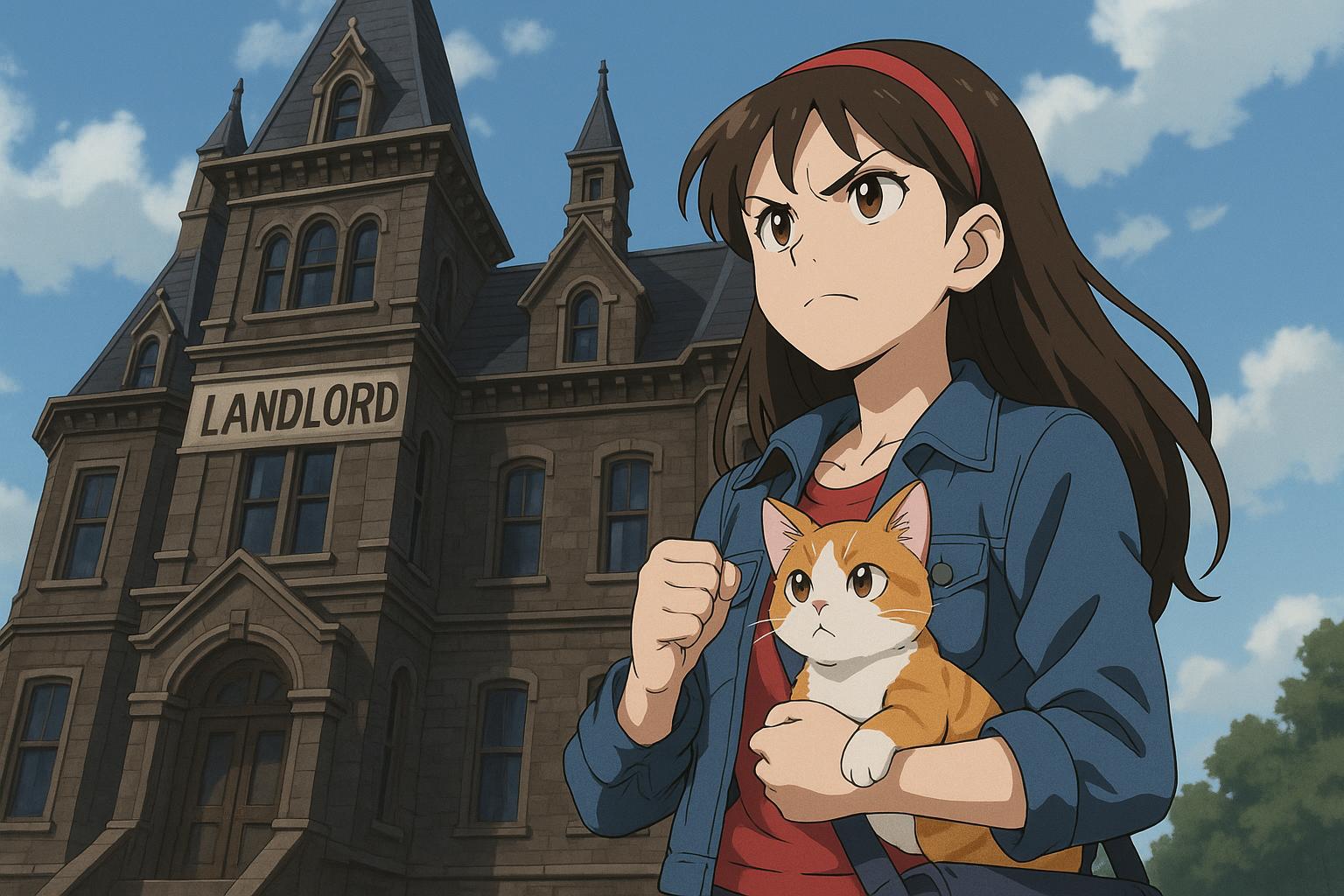

The ongoing debate in the UK’s House of Lords regarding the Renters’ Rights Bill has uncovered the stark realities tenants face, particularly when it comes to keeping pets in rented accommodations. With a mere seven per cent of landlords allowing pets, it’s evident that many animal lovers are trapped in a restrictive rental market that prioritizes landlords' interests over tenants' rights and well-being. The legislative push by certain Conservative peers to amend this law, while ostensibly about animal welfare, raises deeper questions about whose rights are being truly represented.

Proponents of allowing tenants to keep pets argue that this change could improve mental health outcomes and reduce pressure on the National Health Service. But these claims risk becoming mere rhetoric unless they are backed by robust evidence. Far too often, discussions around tenant rights devolve into bureaucratic hurdles that fail to address the real needs of citizens struggling to find homes that accommodate their beloved animals.

As the Lords navigate this complex issue, the concerns voiced by landlords reflect an obsession with profit rather than a commitment to creating a thriving rental market. Questions about what constitutes a “pet” highlight the ridiculousness of the current system. While lawmakers worry about the implications of allowing dangerous breeds, the truth is that their reluctance to adapt reflects a fundamental failure to put tenants first.

Lord Howard of Rising's insistence that landlords retain power to refuse pets based on potential risks shows a disturbing lack of understanding about the real-life implications for tenants. Are we to accept a system that prioritizes landlords’ fears over the mental health and emotional needs of individuals simply seeking companionship? Such attitudes further entrench the divide between tenant rights and landlord interests, benefitting a system that is fundamentally unequal.

Compounding this issue is the misguided notion that animal welfare is at the forefront of this discussion. Baroness Fookes' remarks about ensuring that animal welfare is considered become irrelevant when the core issue—empowering tenants to make choices about their lives—remains overlooked. This is not an issue of balancing rights; it’s about dismantling a culture that puts profit above people.

In an era of increasing scrutiny over tenants' rights, the exclusion of pet ownership from rental agreements serves as a glaring example of how policies often prioritize landlords’ interests over the human experience of home. If we dare to delve deeper into this issue, we might find that the refusal to adapt rental laws reflects a broader societal unwillingness to genuinely support community well-being and belonging.

The historical anecdotes shared by some Lords may evoke nostalgia about the human-animal bond, but they do little to change the present landscape of rental policies that are fundamentally out of touch with reality. For as long as regulations echo the priorities of landlords over the needs of tenants, the experience of renting in the UK will continue to suffer. As discussions unfold, one must question whether the Lords will choose to side with outdated interests or move toward a future where tenant rights and well-being take precedence.

For now, it’s clear that any attempts to reform pet ownership rights in rental agreements will face an uphill battle, reflecting a system still resisting necessary change. Tenants deserve options that support their mental health and enhance the fabric of community life, rather than navigating a maze of legislative hurdles designed to protect landlords.

Source: Noah Wire Services