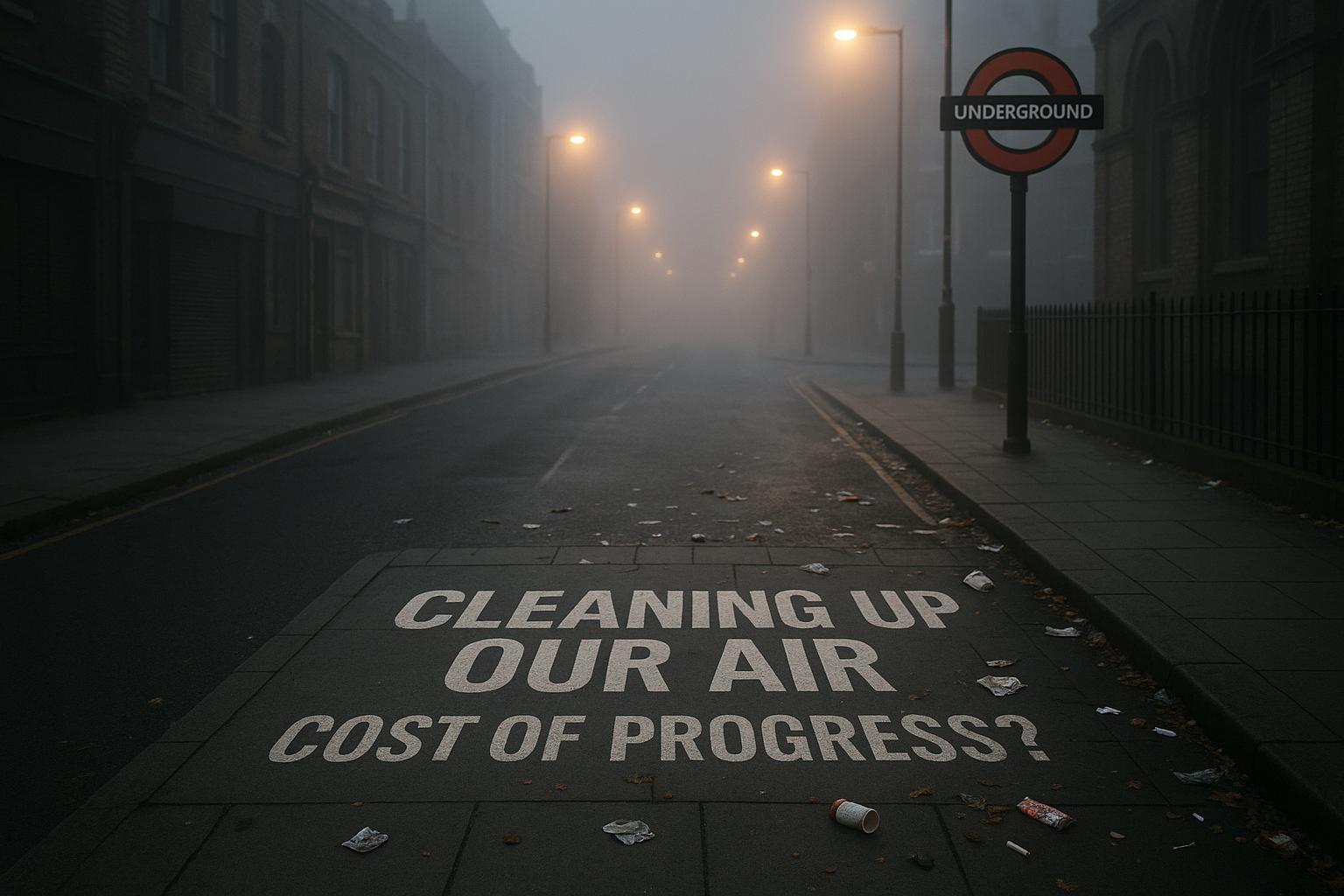

London has marked a notable environmental milestone, achieving legal nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) pollution limits for the first time—a target experts once predicted would take nearly two centuries to attain. While Mayor Sadiq Khan calls this a triumph of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) and the city's targeted policies, critics are right to remain skeptical about how meaningful this milestone truly is.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) reported that in 2024, London met the annual mean NO₂ limits set by UK air quality standards. But let’s not forget: this so-called success comes after years of what can only be described as aggressive and costly intervention, driven by Khan’s administration since 2016. While City Hall boasts that roadside nitrogen dioxide levels have nearly halved, this achievement appears more to be a result of government mandates than a genuine commitment by all Londoners. Critics have pointed out that the rapid drop coincided with the massive expansion of the ULEZ—covering every London borough after its August 2023 extension—to create the world’s largest pollution charging zone. Notably, this restriction has imposed significant hardships on small businesses and residents, with opposition from many who see it as an overreach cloaked in environmental concern.

Khan praised the milestone, claiming London met legal NO₂ limits “184 years early,” citing research that in 2019 warned compliance would have taken over 190 years without intervention. Yet, it’s important to question whether immediate health benefits—such as reductions in asthma, dementia, and heart disease—are as widespread as claimed, especially considering the localised and seasonal variations in pollution. Critics argue that the push for strict pollution controls is primarily driven by political ambition rather than sound public health science.

Independent experts, like Professor Frank Kelly of Imperial College London, have hailed the progress as “remarkable,” but again, this “turnaround” underscores the importance of scrutinising how much of it is attributable to policy rather than natural fluctuations, weather patterns, or technological advancements beyond government influence. This success, however, stands in stark contrast to other major UK cities—Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool—where nitrogen dioxide levels remain stubbornly above legal limits despite similar measures.

Since the ULEZ extension, compliance among vehicles has reportedly increased, with a 10-percentage point rise to 95% within two months. But critics argue that such short-term figures overshadow the long-term impacts. The Bromley Council report from September 2024 noted that in outer London, pollution levels, including NO₂, did not immediately decline following the expanded scheme—in some cases, measurements actually increased, likely due to seasonal weather variations. This calls into question whether the ULEZ’s current design and enforcement are truly effective, or merely a superficial fix.

Amid legal challenges from Conservative-controlled councils attempting to block the extension, the High Court approved the scheme—yet under the new political landscape, there are concerns about the sustainability of these measures. Khan has promised that there will be no dilution of ULEZ rules, maintaining the £12.50 daily charge, but many question whether this relentless focus on punitive charges and restrictions ignores more practical and economically balanced approaches. Critics argue that policies like these risk stifling economic growth and personal freedoms, all while promising incremental pollution improvements that are still fragile at best.

Achieving legal NO₂ levels is indeed a milestone—an effort driven by years of political will and heavy-handed policy. However, London’s experience should serve as a cautionary tale, highlighting that such interventions can be more costly than beneficial, and that genuine, long-lasting solutions require more nuanced approaches. As the city celebrates this supposed victory, opposition voices remain wary: real progress on air quality should not come at the expense of economic sustainability or civil liberties. The challenge ahead is whether this political push for “clean air” is truly about public health, or simply about imposing a narrow, ideologically driven agenda.

Source: Noah Wire Services