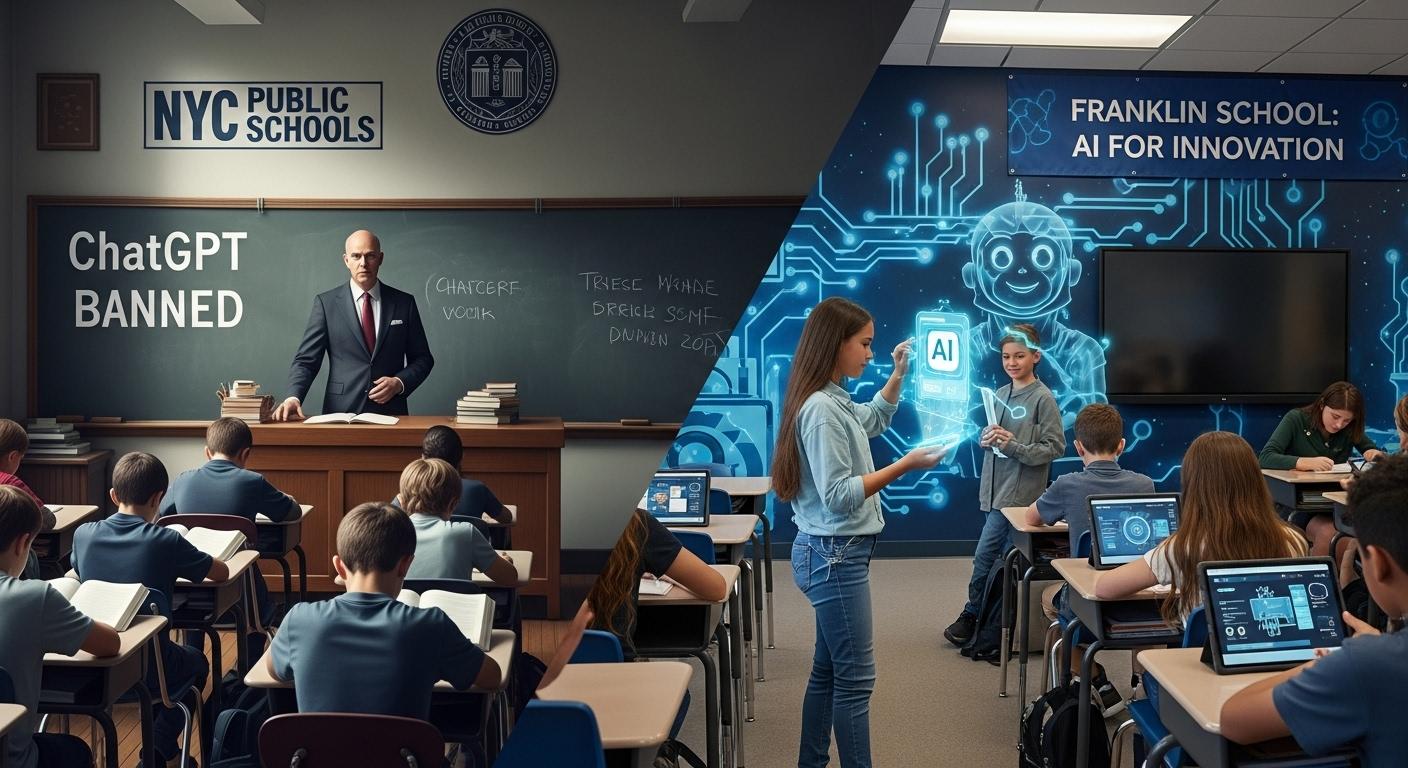

Within months of ChatGPT's public debut at the end of 2022, the New York City Department of Education moved to block access to the chatbot across the city's public school network, citing concerns that it "would have negative impacts on student learning" and warning about the security and accuracy of its content. The move, intended to prevent misuse such as cheating and to protect development of critical-thinking skills, contrasted sharply with other schools that embraced the technology as a learning tool. According to ZDNet, the ban applied to devices and networks within the public system, though individual schools could seek exceptions for instructional purposes. [1][2][3]

By contrast, Franklin School in Jersey City adopted AI as a central plank of its curriculum shortly after opening in 2022, using the tools to augment teachers' work and to deepen student engagement rather than to replace human instruction. Will Campbell, head of Franklin School, told ZDNet they "looked at the integration on how to enrich the learning for students, but also, at the same time, we wanted to see where we could create efficiencies at our school for our teachers." The school's approach has since attracted external recognition: Franklin was named the winner of the 2025 World's Best School Prize for Innovation, an accolade that highlights its technology-driven, student co-designed learning model. [1][4]

Franklin's curriculum emphasises applied learning and practical skills, with explicit courses in artificial intelligence, data analysis and machine learning alongside systems thinking for younger students. The school experimented with custom chatbots trained on approved course material to function as tutor-like aids, redesigned assessments to allow AI-assisted problem solving, and showcased student work and prototypes at annual exhibitions. School materials describe a Maker curriculum that teaches programming, fabrication and robotics, reinforcing the institution's philosophy of learning by doing. [1][5][6][7]

At the university level, some educators have openly encouraged structured AI use. Ethan Mollick of the Wharton School added AI-use guidelines to his syllabus in January 2023 and has since advocated for integrating AI into teaching practice. "We have some early evidence that it's an incredibly powerful teaching tool," he told ZDNet, arguing that many students realistically lack access to high-quality human tutors and that AI may meet or exceed the best support those students can obtain. Mollick uses a "BAH" test , whether an AI is Better than the best Available Human a student can realistically access , and concludes that, in many cases, AI already passes that test. [1]

The impetus for integrating AI into education is often framed as an attempt to close the longstanding tutoring gap. Decades of research, including Benjamin Bloom's seminal "2 Sigma" finding, show large learning gains from one-to-one tutoring, but high costs and staffing constraints keep such support out of reach for most families. Recent surveys and studies cited by ZDNet found that only a small fraction of students receive any tutoring and that high-quality tutoring is even rarer, especially among lower-income students , a disparity that proponents of AI argue the technology could help mitigate. [1]

Proponents point to AI's practical advantages: natural language models can answer questions conversationally, explain concepts, and provide detailed feedback in time-consuming areas such as writing and coding; they can also free teachers and teaching assistants to focus on higher-order instruction. Michael Hilton of Carnegie Mellon observed that students increasingly use AI for basic queries, leaving office hours available for conceptual work. Edtech providers such as McGraw Hill and Khan Academy have framed AI as a scaffold rather than a substitute, building learning experiences first and using AI to support those designs; Khan Academy's Khanmigo, for example, aims to teach students how to use AI productively while scaffolding learning for groups such as English language learners. [1]

Yet pilots and early studies have exposed both limits and hazards. Upchieve, an edtech nonprofit offering free tutoring to low-income students, experimented with UPbot, an AI chatbot trained on tens of thousands of math tutoring transcripts; uptake was low and only a tiny share of sessions were AI-only, with students citing the value of human connection. The study found no statistically significant difference in learning or confidence between human-only and AI-only sessions, and leaders cautioned that AI could unintentionally widen inequalities if affluent students are better positioned to exploit the tools. Brookings and other analyses underline cost barriers for scaling high-impact human tutoring, but also warn that unequal broadband access and digital literacy could blunt AI's promise. [1]

Those tensions have shaped how schools and companies deploy AI: many favour models that keep humans in the loop, use AI to increase educators' reach, and embed AI tools in classrooms to reduce access disparities. As Dylan Arena of McGraw Hill put it to ZDNet, companies must decide whether an AI tutor that is "good enough" for students with few options is an equitable solution, or whether the bar should be higher , a debate that frames ongoing development. The practical outcome in many places is incremental adoption: classroom deployments, teacher-guided AI tools, and learning modes designed to prompt student reasoning rather than provide answers outright. [1]

The divergent responses , from system-wide bans intended to preserve traditional pedagogical aims to proactive curricular integration and innovation prizes , underline a transitional moment for education. Industry data and pilot studies suggest AI can expand access to tutor-like support and free educators for higher-level work, but evidence on long-term learning gains and equity impacts remains mixed. As schools, nonprofits and vendors refine practice, the policy and pedagogical choices they make will determine whether AI narrows or widens existing gaps in opportunity. [1][4][5][6][7]

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- [1] (ZDNet) - Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, Paragraph 3, Paragraph 4, Paragraph 5, Paragraph 6, Paragraph 7, Paragraph 8

- [2] (The Guardian) - Paragraph 1

- [3] (The Washington Post) - Paragraph 1

- [4] (PR Newswire) - Paragraph 2, Paragraph 8

- [5] (Franklin School website - Skills Curriculum) - Paragraph 3, Paragraph 8

- [6] (Franklin School website - Student showcase) - Paragraph 3, Paragraph 8

- [7] (Franklin School website - Academics) - Paragraph 3, Paragraph 8

Source: Noah Wire Services