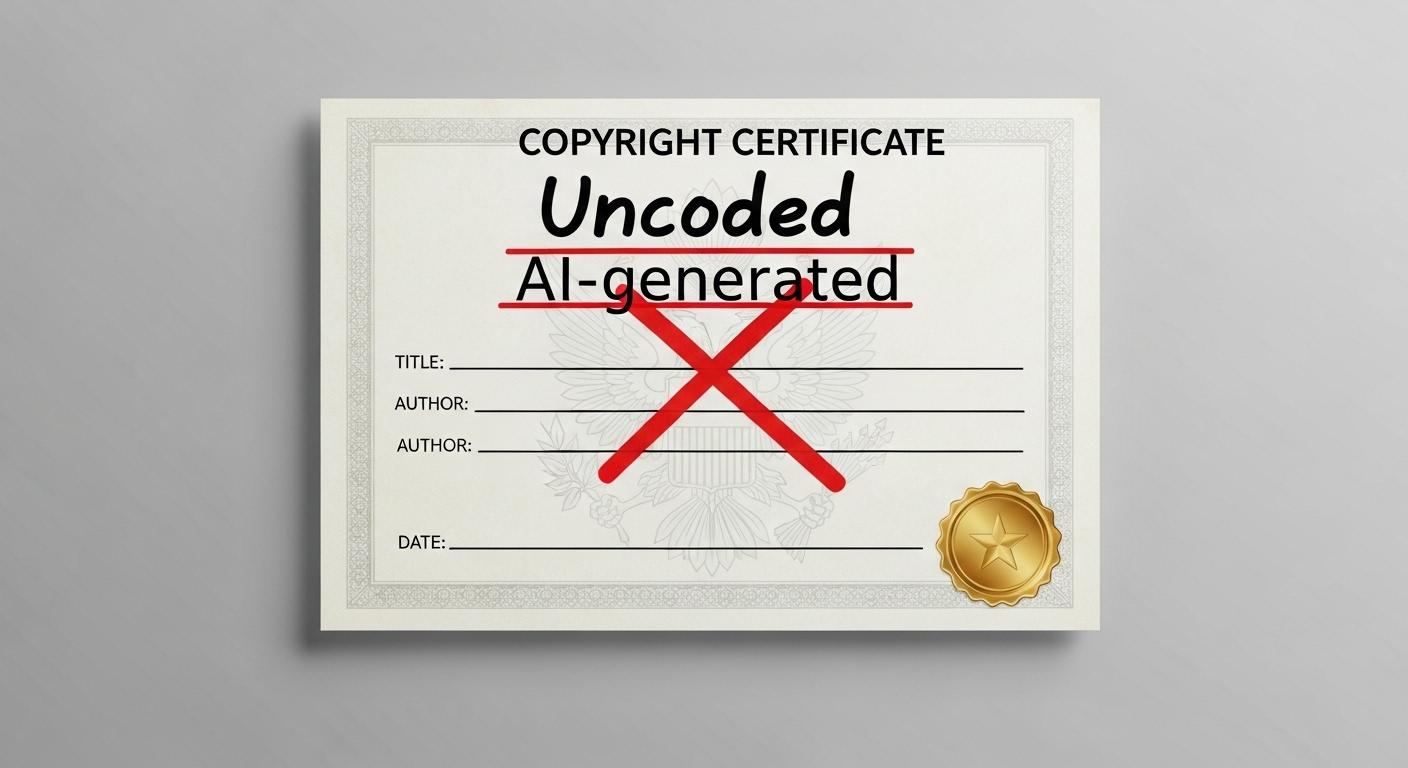

The rapid rise of generative artificial intelligence has exposed a persistent fault-line in Indian copyright law: the statute is silent on whether creativity produced by machines can attract the exclusive rights traditionally reserved for human authors. The Indian Copyright Act, 1957, grants protection to “original” literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works and establishes the author as the first owner of copyright, but it does not expressly recognise non‑human entities as authors, leaving a large grey area as generative models produce text, images, audio and video that can be indistinguishable from human work. [1][2][4]

Section 2(vi) of the Act treats computer‑generated works by declaring that “in relation to any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer‑generated, the person who causes the work to be created” is treated as the author, while section 17 makes the author the first owner subject to limited exceptions such as employment or commissioned works. That language has been read in divergent ways: some argue it can be interpreted broadly to attribute ownership to the human who “causes” the output,while others say the statute remains fundamentally human‑centric and therefore fails to address fully autonomous AI creation. [1][7][2]

Practically, AI‑produced creativity falls into two categories that matter for legal analysis: fully autonomous outputs generated without meaningful human creative input, and AI‑assisted works where a human provides substantial direction, edits or compositional control. Indian and comparative commentators note that the latter category is more readily shoehorned into existing copyright doctrines because human contribution may satisfy the originality threshold. Examples discussed in the literature include an experimental novel assembled by an AI during a US road trip, and the illustrated comic Zarya of the Dawn, where AI produced visuals under human storytelling and editorial control. [1][2][3]

A high‑profile test of the Indian regime came with the registration of “suryast”, a work produced using an AI tool called RAGHAV that stylised a human photographer’s base image in the manner of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night. The Indian Copyright Office initially granted registration listing both the human artist Ankit Sahni and RAGHAV AI as co‑authors, marking what has been described as the first such administrative credit in India. The office later issued a withdrawal notice seeking clarification about RAGHAV’s legal status under the Act’s definitions, reflecting internal administrative uncertainty rather than a definitive legal ruling. Sahni’s separate application to the US Copyright Office was rejected, and subsequent appeals were dismissed. [1]

The international context is fragmented. The United States Copyright Office and some US courts have insisted on human authorship as a bedrock requirement; the US review board treated “suryast” as lacking the necessary human authorship and characterised the registration as involving derivative authorship that did not contain sufficient original human contribution. Recent litigation has underscored that works must exhibit human creative input to qualify under 17 U.S.C.§102(a). By contrast, Chinese courts have at times been more flexible: in a November 2023 case the Beijing Internet Court recognised copyright in an image created using Stable Diffusion where the plaintiff’s prompt engineering and compositional choices were found to reflect his creativity. The European Union follows a standard of “author’s own intellectual creation” derived from Infopaq jurisprudence, a test that similarly privileges human originality. [1][3][4]

These jurisdictional differences carry practical consequences for creators, platforms and rights holders. Industry observers warn that inconsistent standards will complicate cross‑border licensing, enforcement and the attribution of liability where infringing material is used for model training or appears in downstream outputs. Data indicates that large language and image models are trained on extensive corpora that include copyrighted works, intensifying disputes over whether training and generative output infringe or otherwise implicate third‑party rights. Commentators in India and abroad have therefore urged clearer legislative guidance and policy frameworks to balance innovation with the protection of authors’ interests. [2][3][6]

From a doctrinal standpoint, Indian case law emphasises a low threshold for originality measured as a minimal degree of creativity or skill; key precedents such as Eastern Book Company v. D.B. Modak have been invoked to argue that detailed human prompts might themselves qualify as protectable literary works. That raises thorny questions: is a highly detailed 1,000‑word prompt a copyrightable “literary” contribution, or does it merely result in a derivative output that remains unprotected absent further human authorship? The current statutory text offers no definitive answer. [1][4]

Policy responses being discussed range from amending the Copyright Act to define authorship and ownership in the age of machine creativity, to administrative guidelines clarifying how the copyright office will treat applications involving AI. According to legal analysts, any reform will need to address at least three points: authorship and ownership when a human exerts meaningful control; the status of fully autonomous AI outputs; and the permissible uses of copyrighted material for training models. Until lawmakers or courts provide clarity, administrators and registries will continue to face appeals and inconsistent grants that reflect the law’s underlying ambiguity. [1][5][6]

For practitioners and creators operating today the pragmatic advice emerging from commentaries is to document human creative decisions, preserve evidence of prompts and iterative edits, and seek contractual arrangements that allocate ownership and usage rights explicitly. Such measures do not resolve statutory uncertainty, but they can reduce commercial disputes while regulators, legislators and courts reconsider how to align intellectual property law with rapidly evolving generative technologies. [2][3][6]

##Reference Map:

- [1] (Legal Service India) - Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, Paragraph 3, Paragraph 4, Paragraph 6, Paragraph 7, Paragraph 8, Paragraph 9

- [2] (India Today) - Paragraph 1, Paragraph 3, Paragraph 6, Paragraph 9

- [3] (Business Today) - Paragraph 3, Paragraph 6, Paragraph 9

- [4] (Drishti IAS) - Paragraph 1, Paragraph 5, Paragraph 7

- [5] (NDTV Profit) - Paragraph 8

- [6] (Indian Express) - Paragraph 6, Paragraph 8, Paragraph 9

- [7] (The IP Press) - Paragraph 2, Paragraph 5

Source: Noah Wire Services