An investigation by The Guardian has revealed that private landlords and hotel owners in England are charging local councils significantly above market rent to accommodate homeless individuals and families who would otherwise be without shelter. This financial dynamic underscores the severity of England’s homelessness crisis, with local authorities paying on average 60% more for rooms in bed and breakfasts, hostels, and other temporary housing than equivalent properties would cost on the private rental market.

Currently, more than 100,000 households in England reside in temporary accommodation, a figure that contributes to the UK having the highest homelessness rate among developed nations when such temporary housing is included. Local authorities are experiencing escalating costs due to the reliance on the private rented sector and emergency housing, as council-owned social housing stocks have declined amid rising rents and reductions in housing benefits.

In the latest financial year, councils in England spent over £2.1 billion on temporary accommodation. London boroughs alone allocate approximately £4 million daily to emergency housing, which accounts for about 75% of their total housing expenditure. For many families, the reality of temporary accommodation is far from a short-term stopgap; nearly 17,000 families have been in such housing for over five years, and 164,000 children are currently growing up in these conditions, the highest number on record.

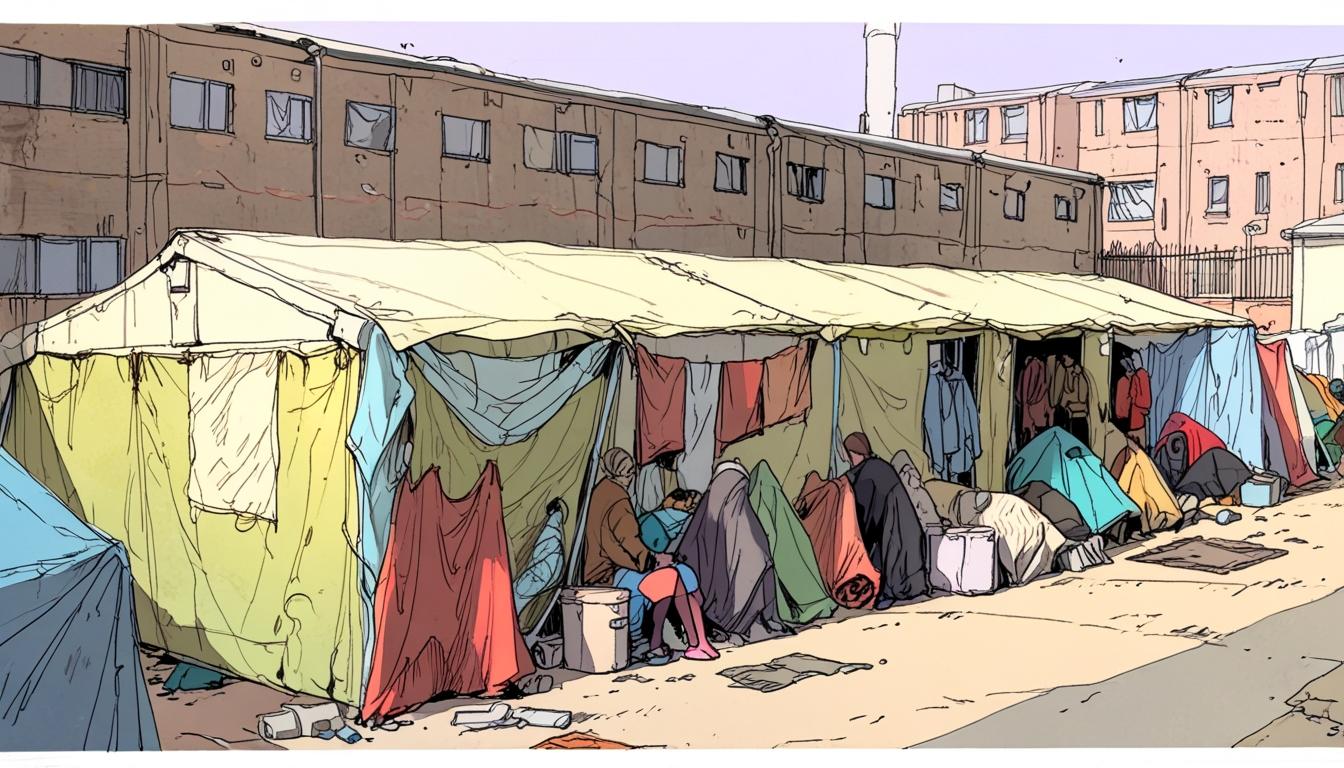

Mairi MacRae, director of campaigns and policy at Shelter, described temporary accommodation as “the shame of our society,” highlighting the prevalence of overcrowded and often appalling living conditions. She added, “It is nothing short of outrageous that private providers have been cashing in on this crisis, but without enough homes for social rent, councils have little choice but to pay these eye-watering sums so families don’t end up on the streets.”

The problem extends beyond financial burdens. The Shared Health Foundation reported that temporary accommodation has contributed to the deaths of at least 74 children in the past five years, with 58 of those under the age of one, illustrating the precariousness and sometimes dangerous nature of the housing. Many providers offering this emergency housing operate with minimal regulation or oversight, setting up a lucrative industry that benefits from councils' desperate needs but at times falls short on quality and safety.

Data obtained through freedom of information requests sent to all councils in England, complemented by publicly available financial and rental market data, sheds light on the scale of the issue. Roughly half of the councils responded, allowing analysis that revealed some local authorities allocate over 20% of their core budgets to temporary accommodation. Hastings, in particular, stands out as spending more than 50% of its core budget on emergency housing but has consciously avoided using bed and breakfasts, which, though common, are considered unsuitable for families with young children despite accounting for 30% of national temporary accommodation spending.

Crawley council has warned that the financial demands of temporary accommodation pose a critical risk to its budget sustainability in upcoming years. The overarching national context shows the UK's homelessness rate, including those in temporary accommodation, to be significantly higher than other developed countries. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) figures indicate that 40 per 10,000 people are homeless in the UK, a rate nearly a third higher than France and double that found in the United States.

Kate Henderson, chief executive of the National Housing Federation, contextualised the growing financial costs by pointing to broader systemic issues: “We are now wasting huge sums of taxpayers’ money on expensive sticking plasters. We are spending £13 billion a year more on housing costs today than we were in 2010, when the government cut funding for new affordable housing by 63%.”

The human impact of the crisis is evident in testimonies from those living in temporary accommodation. One individual, Aimee, recounted to The Guardian her experience in a rodent-infested hotel where sanitation was so poor her children chose to live with their grandmother. Initially informed that she would only stay for 50 days, she remained there for two years, mostly separated from her children. “I got told that housing would be found for me within four weeks of my being there, and it still hasn’t over two years later,” she said.

This investigation highlights the intersection of financial pressures on councils, the growth of a private industry supplying emergency housing, and the enduring challenges faced by families caught in England’s homelessness crisis.

Source: Noah Wire Services