Almost a third of 18‑year‑old applicants to UK universities say they intend to live at home while studying, a striking shift that is reshaping the student experience and sharpening debates about access and affordability. According to UCAS, 30% of those who applied to start degrees in the 2024–25 academic year reported they would remain resident with their families rather than move into student accommodation — up from 14% in 2007 and a long way above the roughly 8% recorded in the mid‑1980s. The organisation’s 2024 application release also confirms continuing regional variation and modest overall growth in applicant numbers.

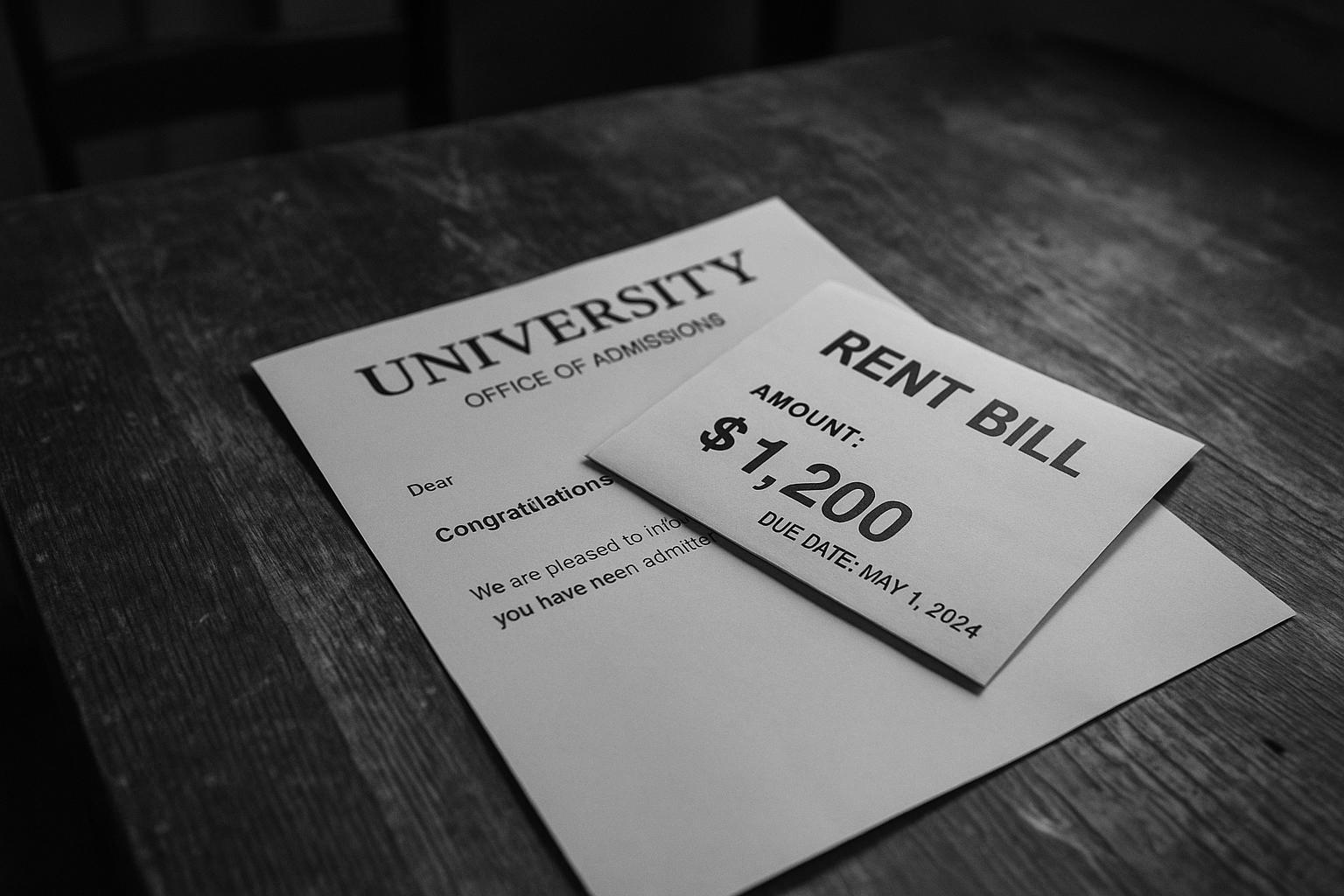

The change is rooted in money. Average annual rents for purpose‑built student accommodation in London reached £13,595 for 2024–25, the Unipol and Higher Education Policy Institute accommodation costs survey found, a figure that now exceeds the maximum maintenance loan of £13,348 and leaves many students facing an affordability gap. The Times reports that typical student borrowing is substantial — recent graduates can leave with debts running to around £53,000 — and that tuition fees are due to rise modestly for the coming year. Financial pressures have been compounded by rapid rental inflation in some markets, prompting sector bodies and commentators to warn of a growing “cost of learning” crisis if maintenance support and the supply of affordable rooms are not addressed.

UCAS’s leaders say the cost‑of‑living squeeze is clearly altering choices. Jo Saxton, chief executive of UCAS, told The Times that while studying at home can be the right decision for reasons such as family responsibilities or course fit, “more needs to be done to ensure the cost of living doesn’t become a limit on young people’s ambition.” The trend is most visible in high‑rent areas and places where fees are lower: London shows strong pressure to stay local because of accommodation costs, while Scottish students are more likely to remain at home where tuition is free. Analysis from sector commentators has also recorded that being “close to home” has climbed the rankings of what applicants value when choosing a university.

The pattern is uneven. UCAS figures show institutions such as Glasgow Caledonian University have very high proportions of first‑year students living at home — almost half of its intake — while Oxford and Cambridge record barely any. The contrast is not just geographic but cultural: the collegiate systems at Oxbridge still bundle room, board and pastoral arrangements together in a way that makes living in college a less marginal choice than the private rented alternatives many students face.

The human stories underline mixed trade‑offs. Several students interviewed by The Times described staying at home as a pragmatic response to cost and a source of social stability. One graduate recounted the comforts of parental support alongside academic success; another said the loss of fresher‑year social life during the Covid lockdowns made moving away feel less attractive. Others stressed that staying at home did not preclude making friends, pursuing extracurricular interests or attending classes — and for some it improved attendance and academic engagement.

Those impressions are borne out by recent survey work. A July 2025 Leeds Beckett University study of 1,000 current UK students found that nearly half live at home while studying. Saving money (64%) and being near family (46%) were the most commonly cited motivations, and 53% of respondents said staying at home encouraged them to attend more lectures and seminars; a slim majority also reported that studying locally did not diminish their sense of belonging. The research suggests many students experience staying at home as a legitimate and positive route through higher education, even as it raises questions about widening participation and social mobility.

At the same time, the market for student accommodation has evolved rapidly, with high‑end private developments offering round‑the‑clock facilities at premium prices. The Times detailed examples of halls charging well over £1,600 a month and private providers advertising gyms, studios and concierge services — amenities that place further distance between average maintenance support and contemporary private provision. That divergence is central to the sector’s current affordability problem and is precisely what the Unipol/HEPI analysis and subsequent Financial Times reporting described as unsustainable for many applicants.

Sector analysts and charities are debating the consequences and possible policy responses. The Financial Times argued that the gap between rents and maintenance support in London amounts to a “cost of learning” emergency and has highlighted calls from universities and experts for a review of maintenance support and for measures to boost affordable supply. Policy‑facing blogs and commentators have urged institutions to make bursary information clearer and to rethink marketing, timetabling and student services to accommodate a larger cohort of “local” students; UCAS has signalled practical responses too, including the launch of a scholarships and bursaries tool to make financial support easier to find. The issue was flagged earlier by other research and advocacy groups, which warned that disadvantaged pupils remain more likely to plan to stay at home.

What is clear is that staying at home is no longer a marginal choice and that it has complex implications for social mobility, institutional planning and student wellbeing. If recent data are a guide, policymakers and universities will need to combine short‑term financial relief with longer‑term action on affordable accommodation, clearer information about bursaries and a sharper focus on how the student experience is delivered when many undergraduates remain local. Without concerted intervention, the sector risks hardening the link between household income and the very choices higher education is supposed to open up.

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [4], [1], [5]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [2], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [3], [1]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 8 – [5], [6], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 9 – [4], [5], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services