Rent to Rent (R2R) in the UK private rented sector has become one of the most controversial property strategies in recent years. At its core, the model involves an operator leasing a property from a landlord on a fixed rent, then subletting it, often on a room-by-room basis, to generate a higher total income. The operator’s profit is the difference after expenses. While the model itself is not unlawful and has legitimate uses—such as housing vulnerable people through charities or local authorities—its portrayal and practice in the wider market have sparked significant concerns.

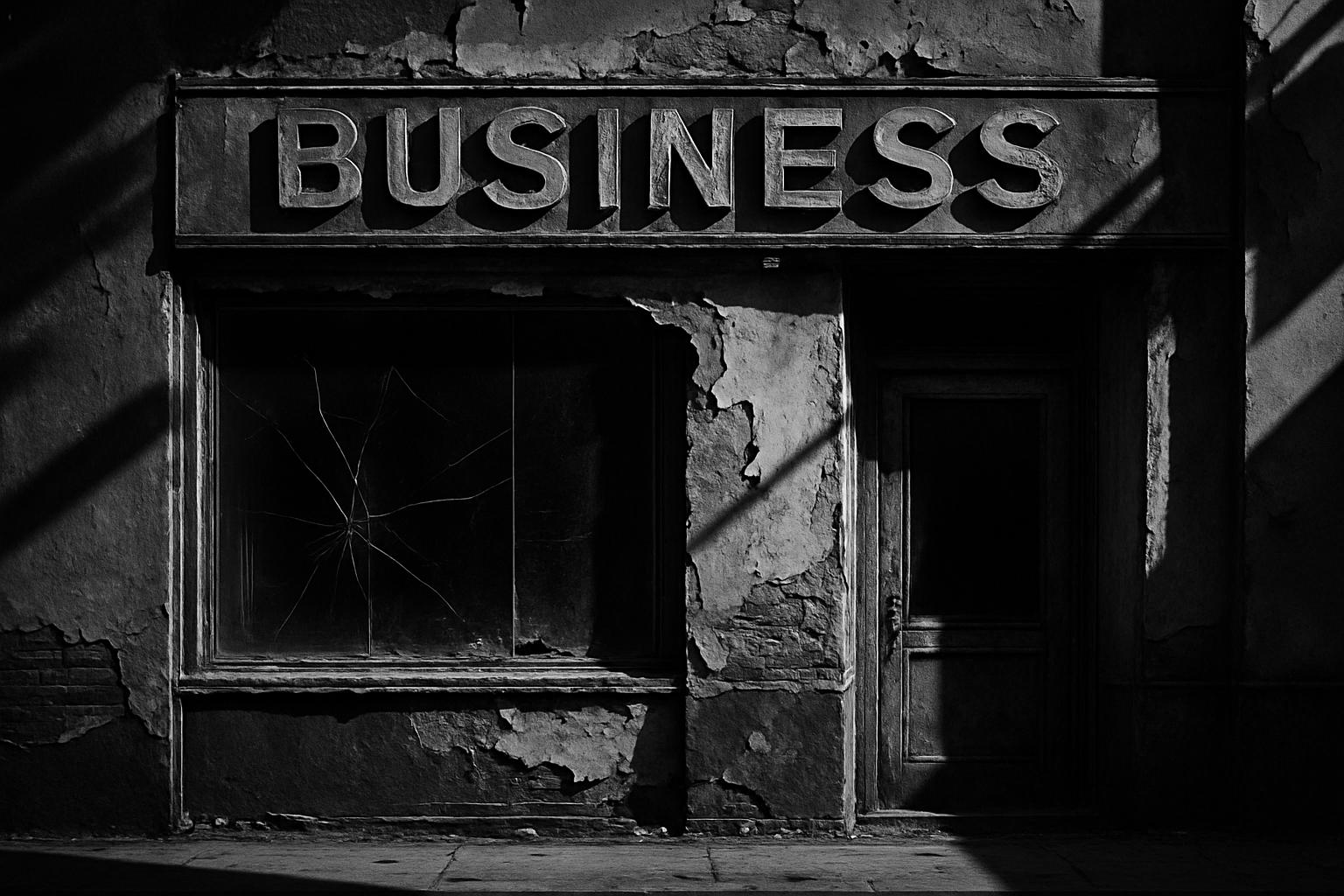

The fundamental problem lies not in the Rent to Rent concept but in how it is marketed, particularly on social media and through paid training courses. These platforms often promise a “low-money-down” fast track to financial independence, guaranteed rent, and passive income, glossing over the complexities and risks involved. Many aspiring operators, driven by these promises, enter the market without sufficient capital, knowledge, or compliance awareness. The result is a worrying trend of business failures, unpaid rent, property damage, and enforcement actions that leave landlords markedly exposed.

A 2023 report from LandlordZONE highlighted that local authorities are increasingly encountering poorly trained R2R operators who misunderstand—and sometimes flout—the legal standards they must uphold, placing tenants at risk and landlords in precarious positions. Common issues include failure to secure the necessary HMO licenses, under-budgeting for essential costs such as licensing fees, fire safety compliance, void periods, and maintenance, and poor tenant screening that leads to higher turnover and anti-social behaviour.

The legal responsibilities for landlords remain substantial even in R2R agreements. Under the Housing Act 2004, landlords are still potentially liable for licensing breaches if their property qualifies as an HMO, and local councils can impose civil penalties up to £30,000 per offence. Furthermore, planning regulations often complicate the scenario, especially in areas subject to Article 4 Directions, where converting a single dwelling to multiple occupancy requires explicit permission. Mortgage and insurance terms usually prohibit subletting without lender consent, and breaches here can invalidate cover, leaving landlords vulnerable to uninsured losses—as seen in cases of fires in unlicensed rented properties.

One landmark legal case, Rakusen v Jepsen (2023), clarified that tenants could only pursue Rent Repayment Orders against their immediate landlord—the Rent to Rent operator—not the ultimate property owner. However, this does not fully shield landlords from disputes, particularly when R2R operators lack assets, often because they operate through limited companies designed to minimize liabilities.

The risks posed by Rent to Rent models are underscored by recent enforcement actions. For instance, Westminster City Council successfully prosecuted an R2R operator for multiple licensing and fire safety breaches, resulting in fines totaling £150,000. Local media coverage of such cases has also impacted landlords’ ability to refinance their properties due to perceived increased risk. Additionally, many landlords suffer financial losses from operators who abandon their leases, leaving behind vast arrears and repair bills.

The introduction of the Renters’ Rights Bill is set to reshape this landscape further, strengthening tenant protections by abolishing Section 21 “no-fault” evictions and extending Decent Homes Standards into the private rented sector. These changes will impose stricter compliance requirements on landlords and operators, increasing the difficulty and cost of managing rental properties, especially for undercapitalised Rent to Rent schemes. Enforcement powers for councils will also be enhanced, raising the stakes for non-compliance.

Despite the negative headlines and myriad pitfalls, Rent to Rent is not inherently flawed or always doomed to fail. In contexts where the model is applied professionally—such as council-led initiatives, supported housing charities, or specialist commercial operators with long-term Full Repairing and Insuring (FRI) leases—it can provide stable, compliant, and beneficial housing solutions. These arrangements typically involve robust funding, experienced management, and strong legal protections that distinguish them sharply from the speculative ventures widely promoted online.

For landlords considering Rent to Rent offers, due diligence is critical. This includes rigorous checks on the operator’s trading history, financial stability, track record of compliance, and the robustness of contractual agreements. Landlords must insist on clear terms covering responsibility for repairs, utility payments, council tax, and insurance. Crucially, they should always notify and secure consent from their mortgage lender and insurer before entering into any such agreement.

Ultimately, the allure of Rent to Rent as a shortcut to easy income is largely an illusion for most landlords. The mismatch between the hyped marketing and the operational realities often leads to costly disputes and hardship. The forthcoming legislative reforms will only amplify these challenges. Therefore, unless the operator is backed by significant experience, capital, and a solid legal framework—as seen in council or charity partnerships—landlords would be wise to approach Rent to Rent schemes with caution or avoid them altogether.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [2], [7]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [5], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [3], [7]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 9 – [1], [2], [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services