Alexander Clapp’s recent book, Waste Wars: Dirty Deals, International Rivalries and the Scandalous Afterlife of Rubbish, offers a thorough and unsettling examination of the global state of waste management, with a particular focus on how industrial waste from wealthy nations has long been offloaded onto poorer countries. The book, published by John Murray in London and priced at Rs.799, delves into the historical, geographical, and geopolitical dimensions of this issue, tracing how waste has become a significant international commodity and environmental hazard.

Clapp’s investigative work reveals how the emergence of environmental regulations in the United States and other parts of the Global North following awareness of pesticide disposal dangers led to a shift in strategy. Instead of fully cleaning up their own waste, affluent countries began exporting hazardous materials—including chemical residues such as asbestos, PCBs, and infectious hospital waste—to countries in the Global South. This waste was often disguised as international aid. For example, agencies like USAID sent large stockpiles of waste to nations such as India, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Haiti, with little regard for the environmental or health consequences.

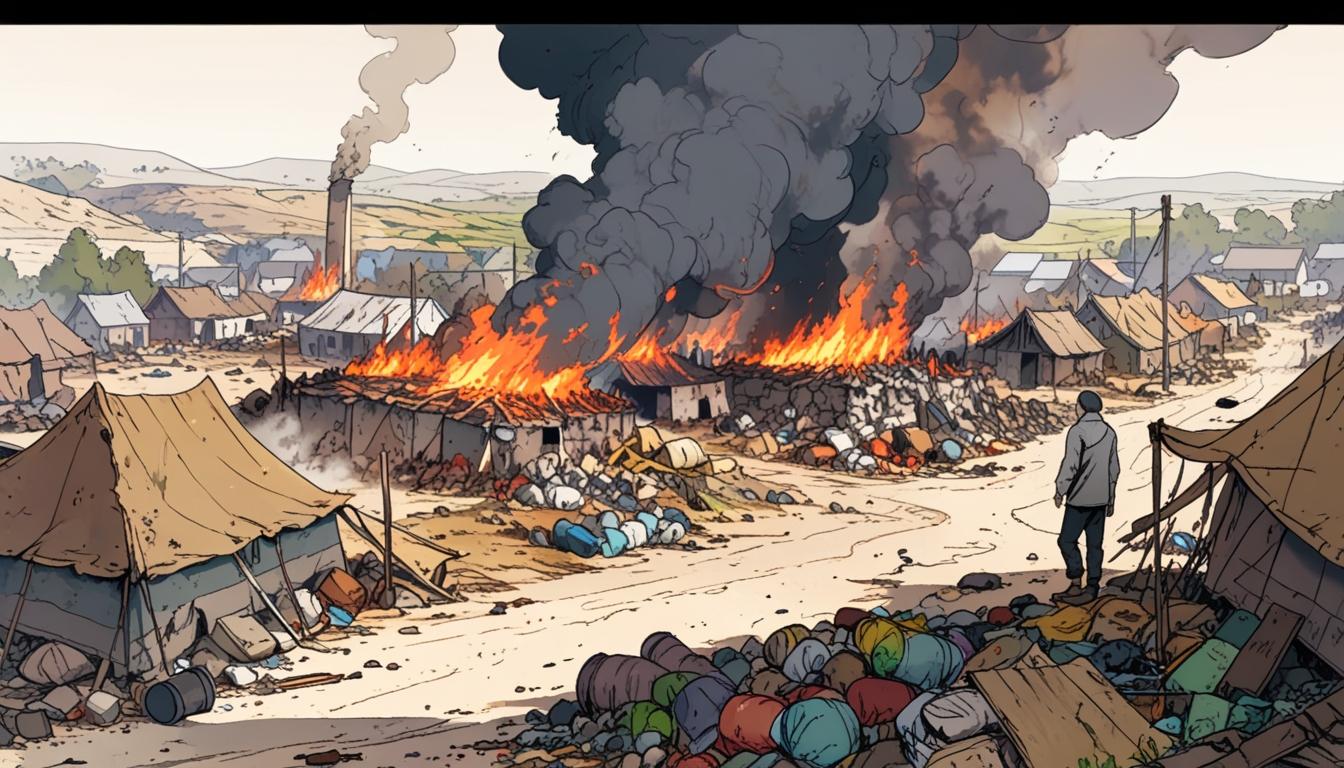

A particularly distressing narrative within the book centres on “waste villages” in East Java, Indonesia. Decades ago, local paper mills operated on abundant bamboo supplies, but once the bamboo was depleted, these mills started importing waste paper from the US and the Netherlands. This waste inevitably included plastic contaminants that could not be returned. The plastic waste was repurposed by villagers, who burned it as fuel in kilns and stoves to produce food items like tofu and crackers. This practice contaminated both the local environment and the food supply with harmful toxins. The soil became barren, animal populations diminished, and water sources turned toxic, yet the villagers continued this practice because burning plastic was economically lucrative. Clapp quotes the villagers’ own words, noting their preference not to return to rice cultivation when burning plastic was "the closest to printing one’s own money."

Turkey’s experience with waste highlights another dimension of the global waste crisis. After the 2018 Chinese ban on plastic imports, Turkey, together with parts of Latin America, Africa, India, and South East Asia, became a disposal destination for scrap materials from the US and Europe. Turkey's construction boom benefited significantly from cheap imports of scrap steel and aluminium, which were recycled and partially shipped back to the West. This pattern illustrates a complex global cycle where hazardous recycling processes are outsourced to poorer regions, while finished goods and waste continue to circulate internationally.

Ghana provides another poignant example of waste’s socioeconomic impacts. The capital city houses Agbogbloshie, one of the world’s largest dumpsites for electronic waste. Young workers dismantle and burn discarded electrical and electronic goods to extract valuable metals like copper. Many engage in sophisticated scams, using data salvaged from these electronics to defraud individuals in wealthier countries. Clapp observes that the blame lies not with these individuals but with the Western world’s failure to properly secure and dispose of electronic devices, thus enabling this hazardous informal economy.

Further illustrating global inequalities, Clapp recounts how waste materials—from toxic lakes in Central America to contaminated steel from the 9/11 attacks—have been shipped to countries ill-equipped to safely manage them. The export of waste often involves complex international manoeuvres, including the renaming of ships multiple times and the installation or removal of compliant governments to facilitate dumping. In Kosovo, the economy revolves almost entirely around waste recycling, carried out by marginalized Roma communities. Ship breaking, a hazardous industry involving dismantling decommissioned vessels often laden with toxic substances, is concentrated in regions from Turkey to Chittagong and Alang in India, where labour conditions and environmental protections are minimal.

Clapp also points out that the United States, despite being the largest producer of hazardous materials, has yet to ratify the Basel Convention, an international treaty intended to prevent the illegal export of dangerous waste to developing countries. This legal omission enables continued waste exports under the guise of foreign aid or development assistance.

Underlying much of the book’s analysis is the concept of “Trumpism,” which Clapp describes not as a recent political phenomenon but as an enduring mindset characterised by extreme self-interest and disregard for the rights and wellbeing of weaker nations. This ideology, according to Clapp, shapes how rich Western countries treat poorer states as dumping grounds for waste, perpetuating a system in which the environment and public health of the Global South are sacrificed for Western convenience and profit.

Despite the grim portrayal of global waste dynamics, Clapp offers glimpses of hope. He highlights the existence of alternative approaches and technologies capable of addressing waste sustainably, ideally by processing waste near its origin rather than exporting it globally. For instance, initiatives in the Indian state of Kerala aim at establishing decentralised, community-driven waste management systems aimed at achieving zero waste. Clapp suggests that such models can serve as both warnings and inspiration for other parts of the world.

The book builds on and updates previous works, such as Waste of a Nation: Growth and Garbage in India by Assa Doron and Robin Jeffrey, by presenting a broader and more alarming global perspective. It challenges readers to acknowledge the complexities and injustices of the global waste trade and to consider the telecommunications, policy, and civic engagement needed to effect change.

P. Vijaya Kumar, a retired English teacher based in Thiruvananthapuram, praises Clapp’s work for its investigative depth and compelling prose, noting that the author’s relentless exposure of hazardous waste sites worldwide offers a unique and necessary contribution to contemporary environmental discourse. Clapp’s book, according to Kumar, is essential reading for those interested in understanding the global dimensions of waste and the environmental and human costs it entails.

Source: Noah Wire Services