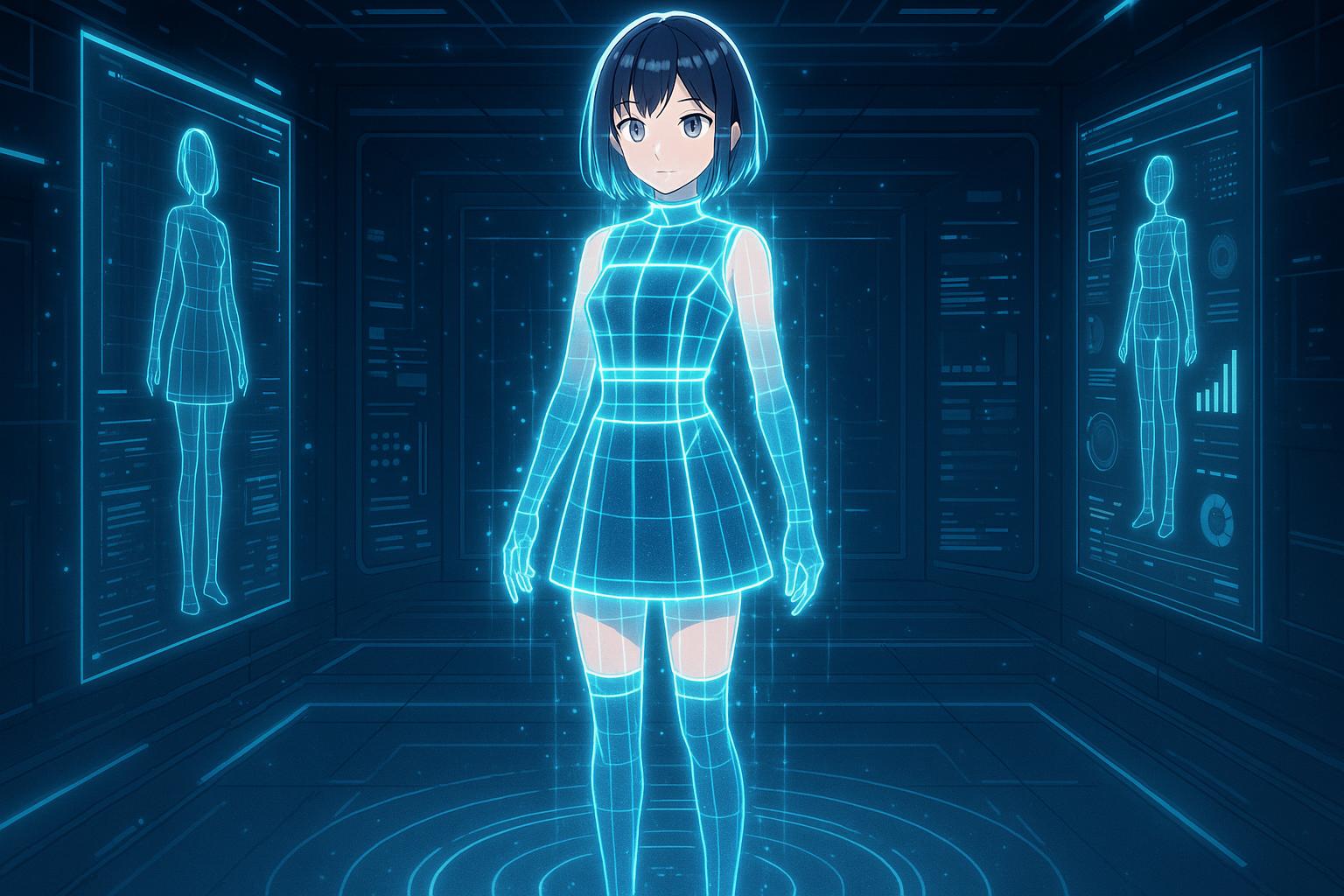

Fast-fashion companies, notably H&M, are increasingly integrating "digital twin" technology—lifelike AI replicas of actual human models—into their marketing and design strategies. This innovative approach, heralded for its potential to revolutionise fashion, relies on extensive processes including full-body scanning and voice modelling to create digital avatars capable of promoting products, interacting with consumers, and virtually modelling clothing.

H&M recently highlighted this shift by unveiling an initiative that cloned 30 real-life models using digital-twin technology. While the company posits that these digital twins can enhance creative expression and streamline marketing efforts, concerns are mounting about the broader implications of such technology. This issue is not restricted to H&M; other brands, including Levi Strauss and Zalando, are also exploring AI models to cut costs and expedite marketing efforts. Zalando, for example, has reported dramatically reduced production times for imagery, achieving remarkable efficiency improvements from several weeks down to just a few days.

However, the advent of digital twins raises critical questions about labor fairness, identity, and environmental impact. The use of AI-generated models introduces apprehensions for fashion professionals—models, photographers, and influencers—who may find their roles diminished as brands pivot towards cost-effective digital solutions. Furthermore, those with established prominence in the industry may harness the technology to enhance their portfolios, potentially sidelining those without substantial followings or industry visibility.

The environmental stakes are substantial as well. Fast fashion is already notorious for generating over 92 million tons of textile waste each year. The introduction of AI models could exacerbate this issue by further minimising the reliance on human labour and, consequently, commitment to sustainable practices. Digital twins are designed to sell physical products, perpetuating a cycle of overproduction that contributes to environmental degradation.

Despite these challenges, there are voices within the industry calling for transparency and fairness in the utilisation of digital twins. Some companies are taking strides to ensure that models retain rights over their digital likenesses, allowing them to control how their image is used. Jul Parke, a PhD student at the University of Toronto, emphasises the necessity of establishing regulatory frameworks that guarantee fair compensation for creative professionals whose identities are digitised.

As this technology continues to advance, it compels all stakeholders—companies, models, and consumers alike—to engage in discussions surrounding ethical practices in AI. For consumers wishing to counter the adverse environmental impacts of fast fashion, opting for secondhand or thrifted clothing can contribute to extending the life cycle of garments and reducing waste.

Amid these developments, H&M asserts that digital twins are intended to complement rather than replace human models, responding to increasing demands for diverse and inclusive representation in fashion marketing. Yet, as the conversation evolves, it is clear that the intersection of AI and fashion necessitates thoughtful deliberation to ensure that both human workers and environmental standards are safeguarded.

The integration of digital twin technology in the fashion industry is transforming paradigms, ushering in novel marketing strategies while simultaneously eliciting a complex array of ethical considerations. What remains crucial is that as the technology expands, it must do so without marginalising the very individuals it aims to represent.

Reference Map

- Paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7: [1]

- Paragraphs 2, 4, 5: [2]

- Paragraph 2: [3]

- Paragraphs 1, 6: [4]

- Paragraphs 3, 6: [5]

- Paragraph 4: [6]

- Paragraph 5: [7]

Source: Noah Wire Services