Universities have grappled with the dual challenge of fear and fascination towards generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) over the past two years, seeking ways to integrate this evolving technology meaningfully into education. While academic staff often debate the risks and potentials of AI, most students simply want clarity on what constitutes acceptable use that supports learning without risking academic integrity. In response to this complex landscape, Royal Holloway, University of London, has developed the AI Collaboration Toolkit, a practical, student-focused framework designed to treat AI not as a threat, but as a literacy to be taught and responsibly integrated into academic work.

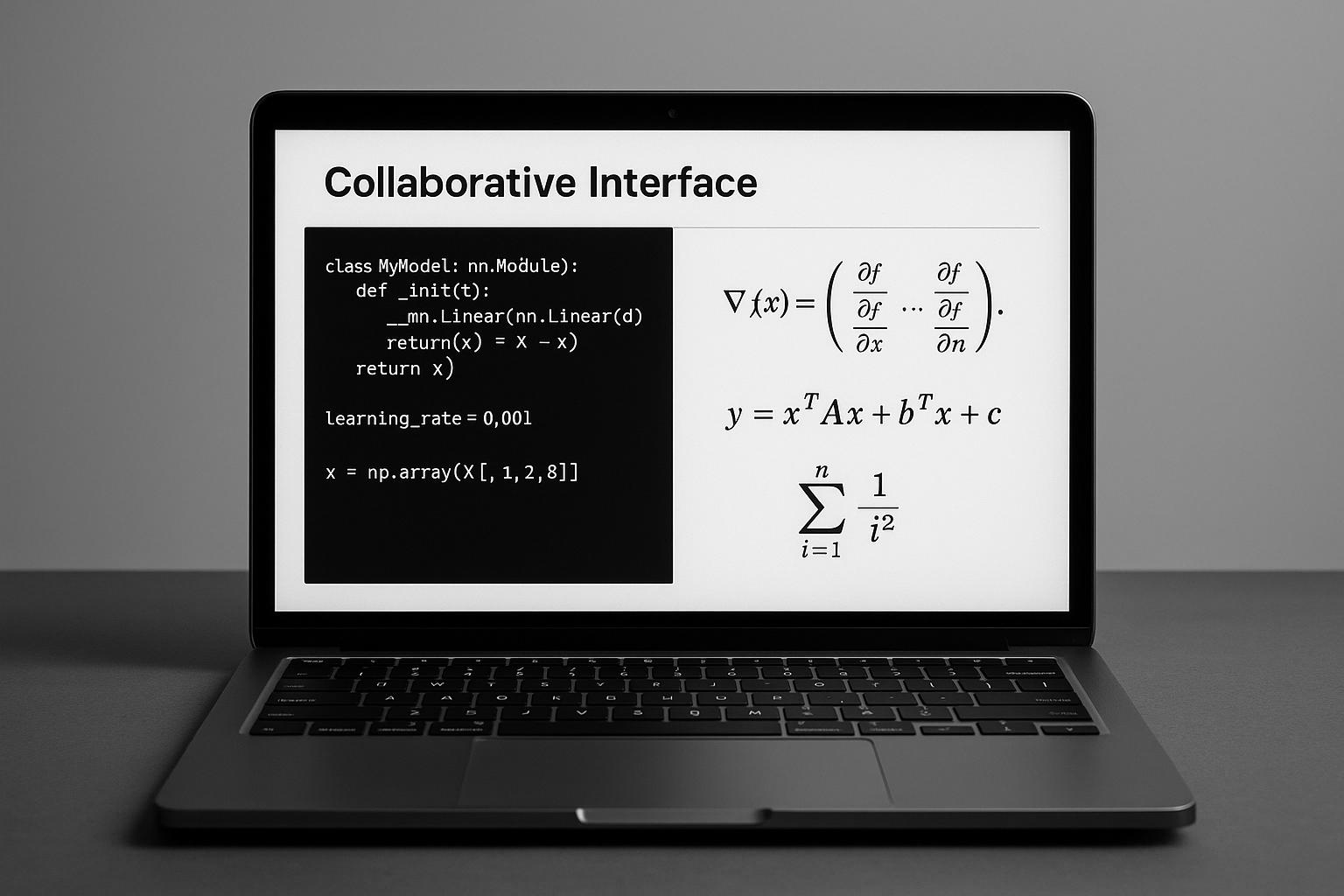

The toolkit rests on a foundational promise: AI exists to augment students' efforts rather than replace their intellectual contribution. Drawing on the late Clayton Christensen’s Jobs-to-Be-Done theory, it encourages students to define the specific task they want AI to assist with—be it brainstorming, structuring, revising, or translating—and to “hire” the appropriate AI tool accordingly, while retaining ultimate accountability for originality and judgement. This approach goes beyond the simplistic binary of “ban it or embrace it” and fosters a disciplined, purposeful use of AI, aligning tools to tasks with human decision-making at the core.

Central to the AI Collaboration Toolkit is a Typology of Student AI Use, a concise matrix categorising common tasks alongside typical AI tools, the roles played by both human and machine, patterns of interaction, and a Red-Amber-Green (RAG) risk rating that signals the acceptability of AI use. For instance, low-risk activities like brainstorming ideas or obtaining formative feedback fall into the green zone, while drafting entire assignments using AI is categorised as high-risk and red. Intermediate, amber-rated activities such as paraphrasing complex texts or auto-generating citations require careful verification and declarations. This typology helps delineate clear boundaries for students and staff, ensuring transparency and fairness in assessment.

Equity and inclusivity are vital considerations within the toolkit. It acknowledges that some students, particularly those who speak English as a second language or have limited access to one-to-one academic support due to caregiving or work commitments, can benefit from accessible AI supports. Fluency improvement and translation of personal ideas are recognised as low-risk with appropriate critical review and clear authorship. The toolkit also encourages AI-assisted planning, structuring, and argument clarification as ways to reduce barriers and foster genuine learning. By defining what “good help” looks like, it offers uncertain students a dignified, supportive framework to develop their work and academic confidence.

To reinforce ethical literacy, the toolkit integrates two reflective practices: an AI Reflection Journal and a Final Self-Check. The journal prompts students to document the task undertaken, the AI’s contribution, lessons learned, and the steps taken to ensure academic integrity. This reflection demystifies AI’s role, transforming it from a black box into a tool subject to critical interrogation. The self-check asks questions such as whether AI was used solely to support thinking, whether the student can explain their work if challenged, and if all citations have been verified, nudging learners toward deeper understanding rather than superficial compliance.

The toolkit also addresses the often confusing terrain of AI-related misconduct through straightforward, plain-English definitions distinguishing AI commissioning (outsourcing authorship), falsification (fabricating data or citations), unauthorised use, and plagiarism (passing off AI-generated content as one’s own). Case vignettes illustrate these breaches in context, helping staff make consistent decisions and students understand the line between acceptable support and academic dishonesty.

Royal Holloway’s approach aligns with broader educational efforts to responsibly incorporate GenAI. For example, University College Cork’s AI toolkit focuses on helping staff and students understand the ethical dimensions of GenAI use in teaching and learning, while LexisNexis offers a curriculum toolkit aimed at developing students’ critical thinking and ethical awareness around AI in academic research. Meanwhile, the University of South Carolina provides interactive modules encouraging ethical AI use in group settings. These initiatives collectively reflect a growing consensus that integrating AI literacy into education should balance opportunity with safeguards, equipping both educators and students for the complexities of GenAI.

Beyond practical guidance, recent academic frameworks such as the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) and its advanced iteration, the Comprehensive AI Assessment Framework (CAIAF), offer structured approaches to determining when and how AI use supports learning objectives. These frameworks advocate transparent decision-making and ethical standards that echo Royal Holloway’s emphasis on purposeful AI collaboration, prioritising human judgement and maintaining assessment integrity.

In practical terms, the AI Collaboration Toolkit envisions scenarios such as that of Amara, an international first-year student balancing part-time work. Amara employs AI judiciously: she uses it to brainstorm case study angles, drafts her own outline, leverages AI for formative feedback on structure and clarity, maintains an AI Reflection Journal, verifies each reference, and completes a self-check before submission with a concise declaration of AI use. When called upon to defend her argument orally, she can do so confidently, demonstrating that the AI supported—not substituted—her learning.

This model highlights the potential shift universities need: moving from fear and policing of AI usage to partnership and capability-building, where rules are clear, transparency is standard, and assessment focuses on genuine learning. Rather than pretending AI is absent or relinquishing authorship to machines, the goal is to teach students to collaborate with AI ethically and inclusively, upholding trust and critical thinking.

For institutions contemplating similar steps, Royal Holloway recommends three initial moves: establish a shared language for AI-enabled tasks, encourage reflective practices that make thinking visible, and permit transparent declarations of AI use. Coupled with alignment of assessment criteria to valued capabilities and joint staff-student training, these steps can nurture integrity, belonging, and improved academic work in the AI era.

Lucy Gill-Simmen and Will Shüler of Royal Holloway’s Schools of Business and Management and Performing and Digital Arts respectively, articulate a vision of AI as a partner in learning—one that demands human oversight but offers new pathways to fairness and creativity in higher education.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 3 – [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 5 – [1]

- Paragraph 6 – [1]

- Paragraph 7 – [1]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [3], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 9 – [1], [6], [7]

- Paragraph 10 – [1]

- Paragraph 11 – [1]

Source: Noah Wire Services