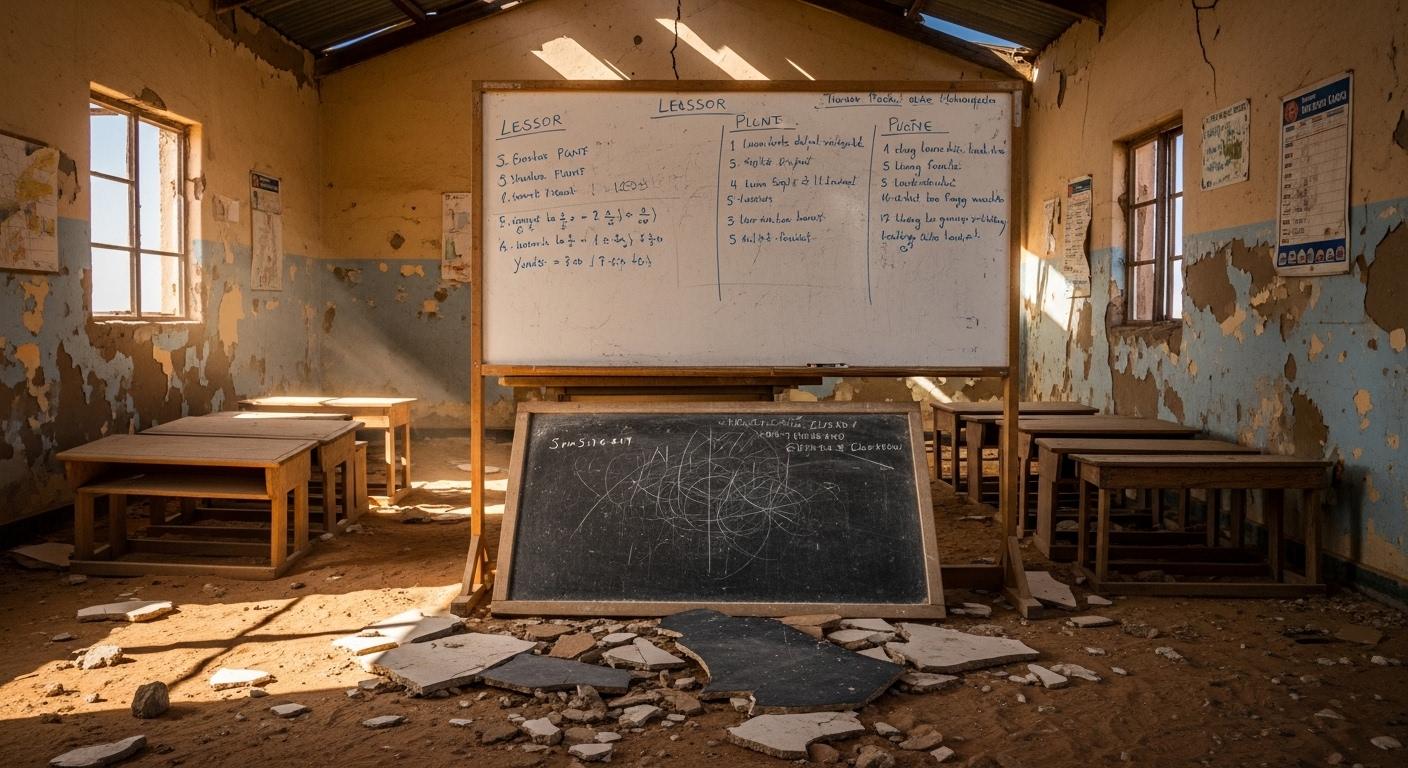

Erastus Nekomba, chair of the Muthiya school board, has warned that a community-led school project in the Omusati region risks failing unless local residents, traditional leaders and government bodies step up to protect and maintain the facility. According to The Namibian, Nekomba said vandalism, a lack of sustained local involvement and weak municipal support have left the project vulnerable and threatened long-term benefits for learners. [1]

Nekomba described how the initial momentum that completed construction has not translated into durable community stewardship, with incidents of theft and damage to materials and infrastructure undermining operations. He said volunteers and donor-supplied resources are being eroded by “opauyelele” , a breakdown in shared responsibility , and urged clearer ownership arrangements between the school committee, parents and the ministry of education. The Namibian report quoted him stressing the need for stronger by-laws and local monitoring to prevent further losses. [1]

Local leaders' concerns mirror obstacles seen in other contexts where community characteristics complicate project delivery. According to a report in The Star about the Nyota youth grants in Garissa County, Kenya, nomadic lifestyles, poor connectivity and limited electricity can blunt the impact of well-intentioned programmes unless interventions are tailored to local realities. That experience underlines Nekomba's point that one-size-fits-all approaches to rural education projects can fail if they ignore mobility, infrastructure and communication barriers. [2]

Project histories elsewhere also show that engaging local technical capacity and managing expectations are crucial. HEAL International's account of a water-supply project at Kimundo Dispensary highlighted how involving local engineers, adapting to weather-related delays and setting realistic community roles helped salvage outcomes when challenges arose. Those lessons support the Muthiya board's call for inclusive planning and for training or incentivising community members to assume ongoing maintenance roles. [3]

Broader research on youth and community participation further explains risks to sustainability. A Harvard study of agribusiness engagement in Papua New Guinea identified cultural norms, high costs and limited access to finance as barriers that keep young people disengaged from local economic projects; similar dynamics can reduce the volunteer base schools need for continuity. Academic reviews of urban and rural development work reinforce that institutional weaknesses, unclear communication and poverty constrain citizen participation unless programmes proactively address those obstacles. [4][5][6][7]

Nekomba has urged the ministry and municipal authorities to formalise support, including assistance with security, supplies and skills training, and to create mechanisms for local contributions beyond one-off donations. He warned that without clearer roles and faster responses to vandalism, the facility risks becoming another unfinished promise rather than a durable asset for children and the wider community. The Namibian noted his appeal for partnerships that combine government, community and non-profit efforts to sustain the project in the long term. [1]

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- [1] (The Namibian) - Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, Paragraph 6

- [2] (The Star) - Paragraph 3

- [3] (HEAL International) - Paragraph 4

- [4] (Harvard Business School Clinic) - Paragraph 5

- [5] (World Journal of Arts, Research and Resources) - Paragraph 5

- [6] (Kampala International University thesis) - Paragraph 5

- [7] (Journal of ARJASS) - Paragraph 5

Source: Noah Wire Services