In 2025, as Britain marks the 200th anniversary of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the professional body ICE London is using the milestone to turn a professional and public spotlight on the engineering that has underpinned the capital’s transport for nearly two centuries. According to the ICE event listing, the seminar will trace London’s rail development from the earliest nineteenth‑century beginnings to the present day and pose a single pressing question: is the city’s railway infrastructure resilient enough for the demands ahead? The bicentenary itself is being commemorated nationally, with museums and curators highlighting the moment when Locomotion No. 1 hauled the inaugural train on 27 September 1825 and set in motion a global rail‑building era.

London’s response to that early railway revolution was quick and, in many respects, pioneering. The Metropolitan Railway — opened in January 1863 by cut‑and‑cover construction to link termini with the City — established the world’s first underground passenger service and laid down techniques and planning responses to urban congestion that still matter today. A generation later the City & South London Railway demonstrated another leap: the first successful deep‑level tube, opened in 1890, that combined tunnelling innovations with electric traction and presaged the dense, mostly underground network Londoners now rely on. Museum collections and interpretive displays emphasise how each technological shift — from steam to electric, from cut‑and‑cover to deep tunnelling — changed both engineering practice and urban life.

That legacy is visible in the modern patchwork of services threading the metropolis: subsurface Tube lines, suburban and intercity mainlines, light rail and, increasingly, high‑speed international services. Eurostar, for example, markets cross‑channel high‑speed journeys as city‑centre to city‑centre alternatives to short‑haul flights, underscoring how London’s rail system is not only local infrastructure but part of a wider European network. The complexity of those overlapping systems — and the way they were built incrementally over different eras — is central to the seminar’s exploration of resilience.

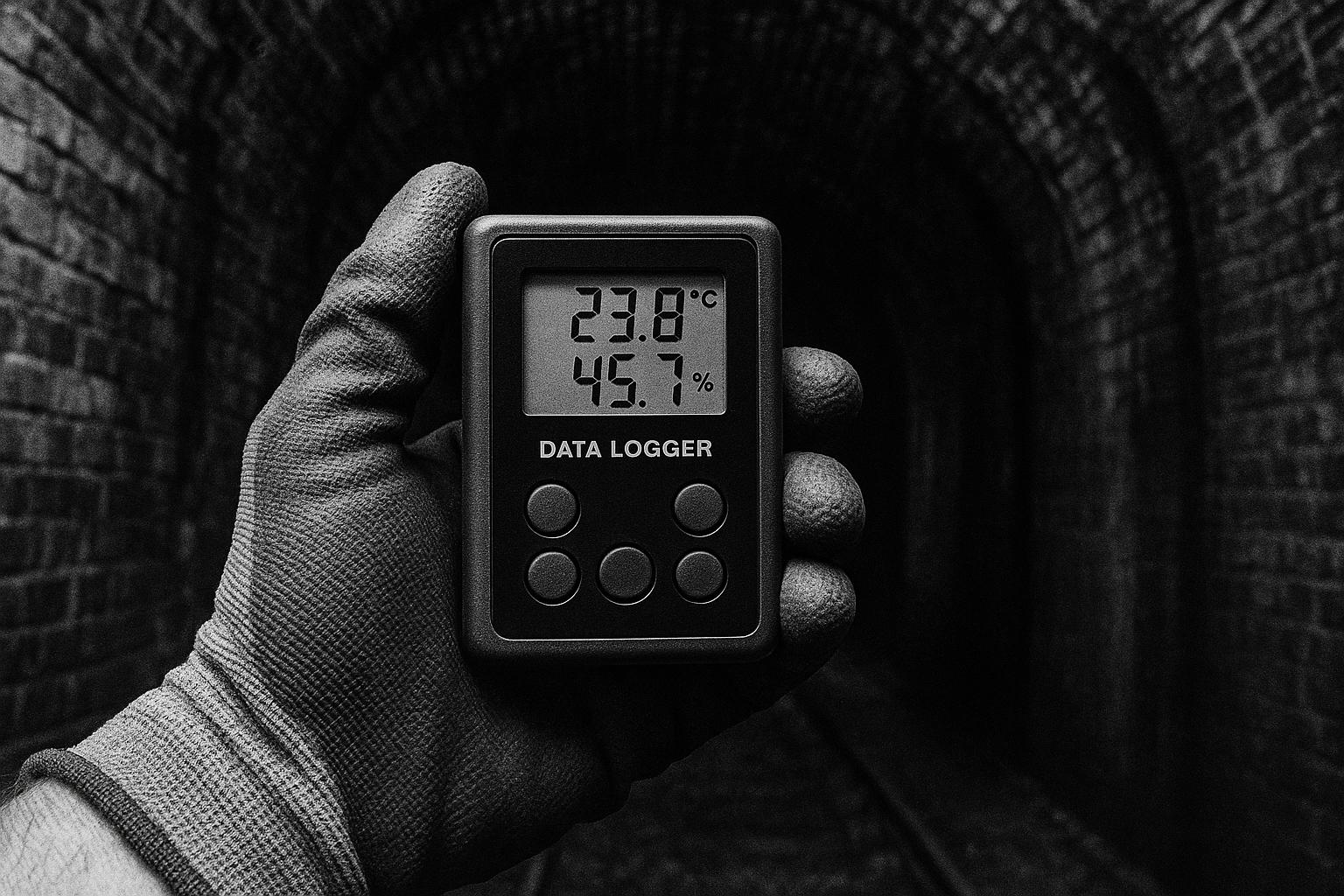

Resilience, in this context, is not an abstract ambition but a practical engineering challenge. Network Rail notes that the network includes hundreds of thousands of ageing civil‑engineering assets — earthworks such as embankments and cuttings among them — many of which were constructed more than 150 years ago. Its published material warns of familiar risks: landslips, water saturation, vegetation impact and the growing stress that extreme weather events place on legacy structures. Network Rail describes a risk‑based approach combining monitoring, drainage improvement, stabilisation and major engineering interventions to keep assets safe and operable.

ICE’s planned seminar brings practitioners to that technical debate. The organiser’s programme lists Network Rail’s Technical Head of Structures, Ben Wilkinson, and One Big Circle co‑founder Emily Kent as keynote contributors, to be followed by a panel including a TfL civil‑works manager and a principal civil engineer from the Rail Safety and Standards Board, chaired by KPMG’s Frederick Levy. According to the event page, the session will combine historical perspective with contemporary case studies and an open discussion on how the industry must evolve to meet future pressures. As this description makes clear, the meeting is as much about professional exchange and scrutiny as it is about commemoration.

The engineering responses on display today build on long‑established techniques as well as on newer asset‑management practices. Network Rail emphasises geotechnical expertise, routine and remote monitoring, improved drainage and targeted stabilisation works as essential tools; industry literature and case studies point to increasingly data‑led inspection regimes and prioritised investment as the way to stretch scarce funding further. At the same time, the historical record — from Victorian cut‑and‑cover tunnels to the pioneering deep tubes — is a reminder that step‑changes in materials, methods and institutional organisation have repeatedly reshaped what is possible.

The bicentenary year has also been used by museums and heritage bodies to re‑engage the public with that engineering history. The National Railway Museum’s programme for 2025 includes exhibitions and conservation work that aim to preserve foundational locomotives and artefacts while explaining how rail transport reconfigured nineteenth‑century economic geography and urban growth. Those public programmes complement technical conversations by making the physical and social stakes of resilient infrastructure visible beyond the professional community.

Ultimately, the ICE London seminar arrives at a moment when commemoration and caution sit side by side. The capital’s railways are a living palimpsest — a working network built across eras of remarkable ingenuity but now facing new climatic, operational and connectivity pressures. As the sector’s own documents and the event organisers suggest, meeting those pressures will require continued inspection, targeted technical interventions, clearer public communication and sustained cross‑sector investment. The bicentenary is therefore less an endpoint than a prompt: to celebrate past achievements while testing whether the engineering decisions of today will keep London moving for the next two centuries.

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [4], [5], [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 4 – [7], [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [7], [4], [5]

- Paragraph 7 – [3]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [7], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services