Sir Tim Rice has suggested he would “consider” using artificial intelligence to help write songs, admitting in a Times Radio interview that he has not yet used the technology “seriously” but would be open to experimenting with “one or two songs.” Speaking to Jane Mulkerrins, the 80-year-old lyricist—best known for Evita and Jesus Christ Superstar—said curiosity rather than fear guides his view of AI’s place in songwriting.

Rice told the programme he had already put a simple prompt to an AI—asking it to compose a Shakespearean sonnet about cricket—and found the result “really quite good,” a small trial that, he said, suggests the technology might be worth exploring more deliberately.

When pressed about wider concerns, Rice struck an unusually sanguine note for a figure of his generation. “If I’m honest, no, I’m not sure,” he said, adding that nobody yet knows exactly what AI will do and even suggesting, somewhat provocatively, that it “might create more jobs.” He also quipped that he would be unconcerned about longer-term consequences unless the machines could “bring me back to life.”

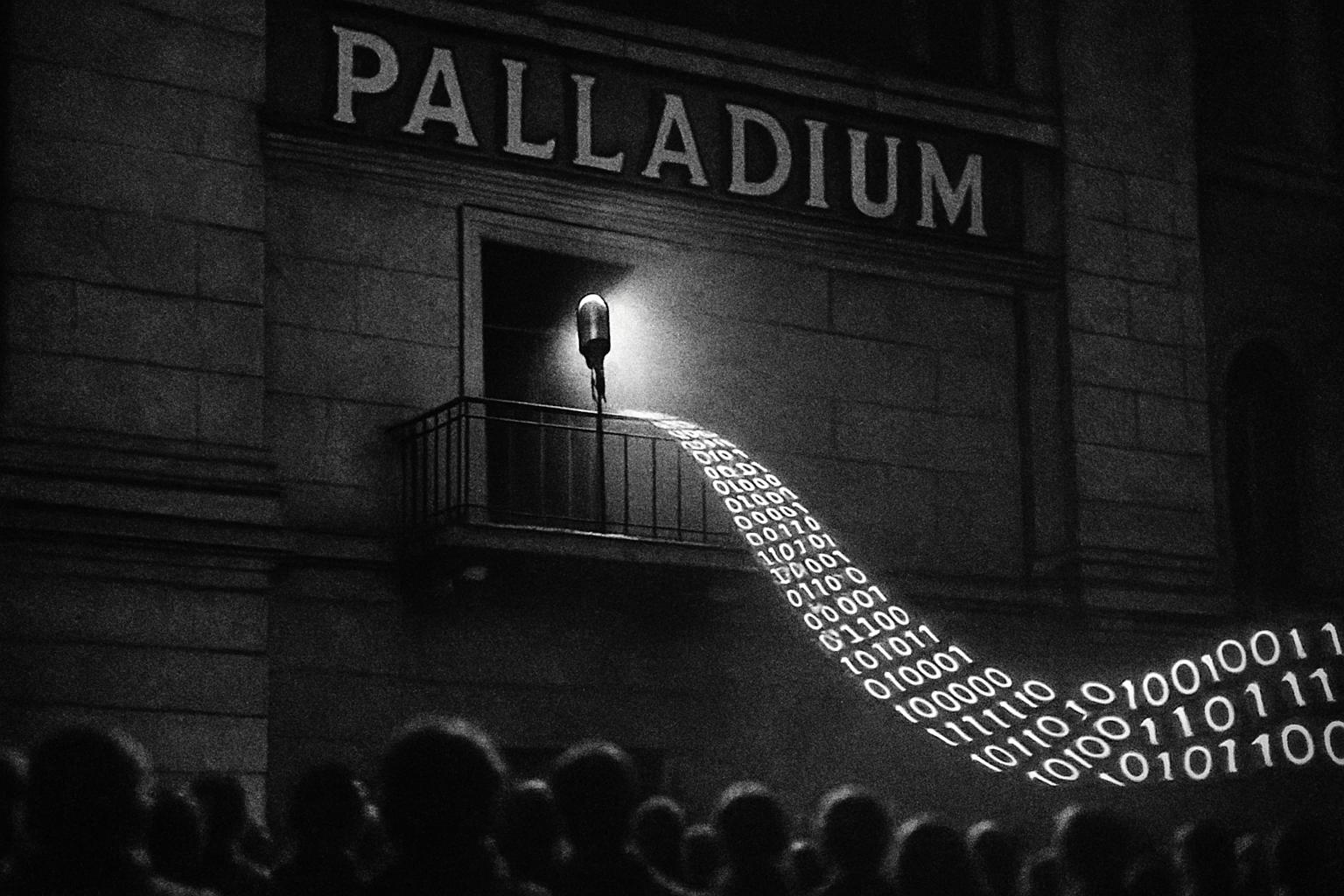

Rice made the comments as attention around his work has been refocused by Jamie Lloyd’s high-profile West End revival of Evita, in which the show’s young star Rachel Zegler performs the show’s most famous number from the London Palladium’s exterior balcony. Rice praised Zegler’s performance, calling her “a force of nature,” and described the idea of the balcony sequence—bringing the song out into the real street—as “a work of genius.”

The unconventional staging has become one of the most-discussed elements of the production. The move to have Zegler sing “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” from the Palladium façade has nightly drawn crowds to Argyll Street while indoor audiences watch a live feed; Andrew Lloyd Webber called the moment “extraordinary.” At the same time, some paying patrons have expressed frustration at watching the filmed sequence rather than seeing the singer live, given premium ticket prices.

Critical reaction has been mixed. Several reviews have hailed Zegler as a revelation and described the production as thrilling and inventive, with reviewers calling the balcony gambit audacious. Others, however, have queried the theatrical logic of relocating one of Evita’s emotionally pivotal moments outside the auditorium, arguing the disruption risks alienating those who have paid to experience the show in person and raising questions about whether the choice is driven by artistic intent or publicity. One prominent critique framed the decision within a Brechtian tradition of foregrounding artifice but warned of the trade-offs involved for audience engagement.

Rice’s comments and the production’s staging together underline a wider truth about contemporary culture: artists and institutions are experimenting with new technologies and forms of presentation, and those experiments often provoke debate as much about access and expectation as about aesthetics or economics. Whether AI becomes a routine collaborator in songwriting, or whether theatre producers continue to redraw the boundary between stage and street, both conversations show how familiar cultural forms are being recast in an era of rapid technological and commercial change.

For now Rice’s stance is clear in tone if not in firm commitment—an openness to try, laced with wry detachment—and the fuss over Evita demonstrates how innovation in the arts can simultaneously attract fresh audiences, generate headlines and unsettle parts of the traditional theatregoing public.

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [2], [3]

- Paragraph 3 – [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [4], [6]

- Paragraph 5 – [4], [5], [6]

- Paragraph 6 – [6], [7]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [4], [6], [7]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [4], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services