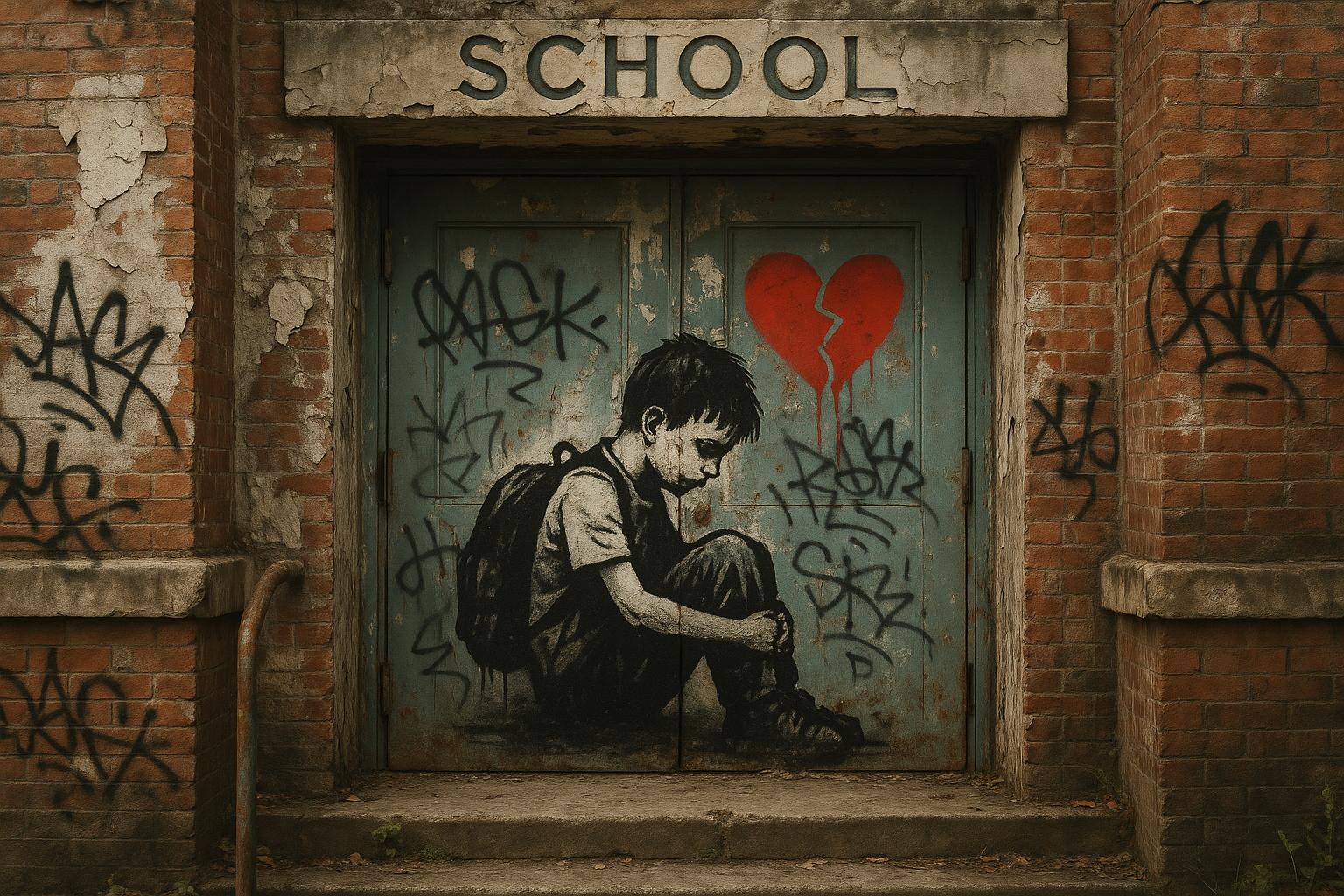

White children from low-income backgrounds are showing troubling signs of disengagement from education as they enter secondary school, according to recent research. A study tracking around 70,000 pupils across more than 100 UK secondary schools found that low-income white children (LIWC) score the lowest for self-reported school engagement upon starting Year 7, averaging just 2.6 out of 10. This disengagement, evident as early as the transition into secondary education, tends to worsen during their first year, signalling early and persistent educational challenges for this group.

Professor John Jerrim of University College London’s Social Research Institute and the ImpactEd Group, who led the research, stressed the importance of early interventions. He suggested that since many low-income white children arrive at secondary school already less engaged than their peers, providing schools with earlier data on engagement could help educators intervene before disengagement leads to poorer academic outcomes. "For years we’ve focused in on the outcomes of low-income White children, but this data shows us that we need to look much earlier on," Professor Jerrim noted.

The research assessed multiple dimensions of pupil engagement, including interest in lessons, school enjoyment, behaviour, relationships with peers and teachers, and effort levels. Low-income white children scored particularly low on measures of effort at school, with an average score of 5.46 out of 10, the lowest among all demographic groups measured. In contrast, non-disadvantaged Asian children recorded the highest effort score at 7.66. LIWC boys were most likely to undervalue their education and report lower effort, while LIWC girls rated their enjoyment and sense of control at school the lowest of any group. Peer relationships were weakest among LIWC students, though mixed-race disadvantaged pupils fared worst in terms of teacher relationships.

The findings align with earlier academic work showing that pupils’ enjoyment of school tends to decline substantially in Year 7, a critical transition period. It also echoes concerns voiced this year following A-level results, when Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson highlighted the lack of progress among children from white working-class backgrounds as particularly troubling. Several educational organisations, including Star Academies, have since launched inquiries into the educational outcomes of white working-class children to understand and address these disparities better.

Broader academic literature supports the significance of early engagement and school readiness in shaping children’s educational trajectories. Studies on younger children from low-income and ethnically diverse backgrounds indicate that positive engagement with teachers and peers, as well as active involvement in learning tasks, are strongly associated with better literacy, language, and self-regulatory skills at school entry. Conversely, negative engagement correlates with lower academic skills and more conflicts with teachers, undermining school readiness and long-term achievement.

Furthermore, research on early achievement gaps suggests disparities often emerge well before children start school and are closely linked to family, childcare, and educational experiences during the preschool years. These investigations have shown that instructional quality and home environments play significant roles in shaping early academic outcomes, highlighting the need for systemic early interventions across both home and school contexts.

Socioeconomic factors such as family income and maternal education influence school readiness and achievement, but their effects may be moderated by broader familial and environmental factors. Studies have found that while income is linked to academic and behavioural measures at school entry, its influence can diminish when controlling for other variables. Family wealth, notably the presence of liquid assets, also impacts cognitive achievement through better home environments, parenting practices, and access to educational resources.

The new UK study on LIWC identifies an urgent need for policymakers and educators to work collaboratively in identifying and supporting disengagement risks much earlier than secondary school. Addressing these early disparities is crucial in preventing the steep decline in engagement witnessed at a pivotal stage in education and opening pathways for improved outcomes for this vulnerable group.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 2 – [1]

- Paragraph 3 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 4 – [1]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [2]

- Paragraph 6 – [3], [4]

- Paragraph 7 – [4], [6], [7]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [2]

Source: Noah Wire Services