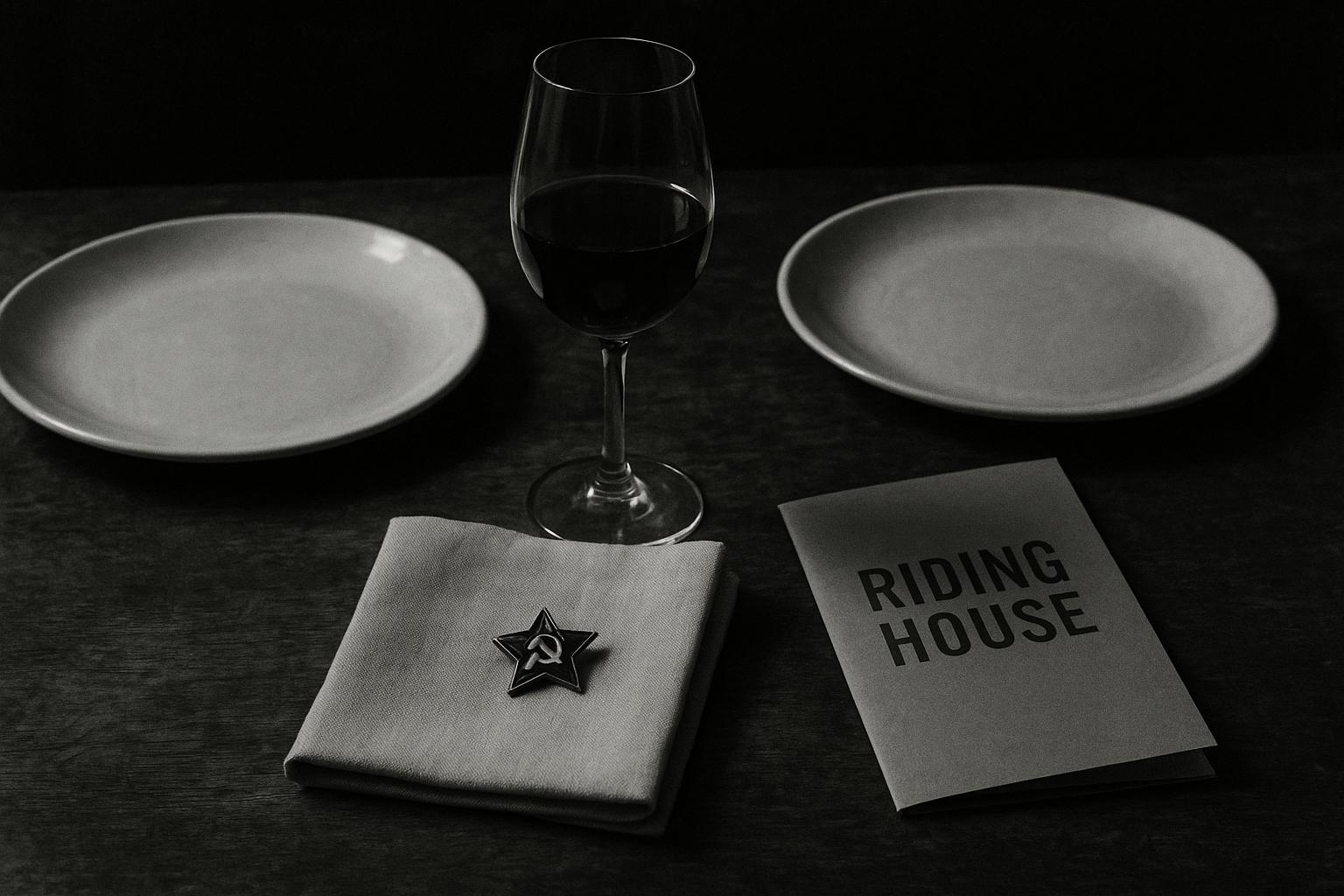

They met at Riding House in Bloomsbury — a modern European restaurant whose menus change with the seasons — and, for two hours over salt and pepper squid, cod loin and a sourdough margherita pizza washed down with a Romanian red, laid out opposing frames for how to think about the nation and its future. The encounter, arranged as part of a Guardian series that pairs strangers from different political backgrounds, brought together Michael, a 38‑year‑old data engineer who began his working life as a history teacher, and Sophia, a 19‑year‑old student and campaigner for the Workers party. According to the original report, their conversation ranged from migration and economics to Gaza and gender politics. (Riding House describes itself online as offering seasonally rotating set menus across several London locations.)

Food, drink and first impressions framed the exchange. Michael told The Guardian he found Sophia “younger than I thought” and noted the communist pins she wore; Sophia said she had expected someone more rightwing and was surprised by his abstention from recent elections. Their meal — the dishes the paper records them eating — fitted the kind of modern European, bistronomy offering the restaurant presents in its public menus.

The meeting quickly turned to migration, where the gulf between them was stark. Speaking to The Guardian, Michael argued that a government’s “first duty of care is to their own citizens” and that migration must “serve the interests of the people already here”; he described the experience of arriving legally from Canada and said the idea that people could simply “show up and not have to wait in line” felt wrong. Sophia countered that migrants are fleeing corruption, poverty and rights abuses and often have little real choice about leaving. She accused Michael of lacking empathy and said his viewpoint treated migrants as economic agents rather than people in desperate circumstances.

Those personal claims sit against a more nuanced picture in the academic literature. A briefing from the Migration Observatory at Oxford notes that evidence shows small overall impacts of immigration on average wages and employment in the UK, while also stressing important variation by sector and skill level — with the clearest modest negative effects tending to fall on low‑paid workers in particular industries. The briefing also highlights methodological challenges in measuring short‑run and long‑run effects and points to gaps in the evidence that make blanket statements about migration’s consequences hazardous.

Michael’s broader economic critique — that current migration patterns sustain a low‑wage labour market, inflate GDP metrics and benefit large corporations — was presented as his interpretation of how the system works. The Migration Observatory’s analysis does not dismiss concerns about sectoral distortions; it emphasises, however, that impacts are complex and uneven, and that policy responses need to account for local labour‑market dynamics rather than rely on sweeping generalisations. Sophia’s rebuttal, that recruiting professionals from poorer countries can damage those countries’ health systems and development prospects, reflected a familiar moral argument in public debate about brain drain versus sanctuary and opportunity.

The pair also clashed over Israel and Palestine. Michael told The Guardian he did not “have a strong opinion” beyond finding the violence “atrocious.” Sophia framed the conflict as unjustifiable nationalist violence and rejected the two‑state approach, saying it would “reward Israel for what it’s done” and advocating instead for a single democratically governed state. Contextual explainer pieces on the diplomacy of the conflict note that the two‑state solution — conceived around the UN partition plan of 1947 and refined through subsequent negotiations — remains the reference point for many diplomats but faces major practical obstacles, including contested borders, the status of Jerusalem, refugees and settlement expansion. Sophia’s one‑state position is one of several competing visions for a just outcome; it reflects a strand of activism sceptical that partition can now achieve equitable or viable results.

Gender and identity were another flashpoint. Michael said that “everybody should have the right to be left alone” and questioned legal rules around misgendering, while Sophia described herself as a gender abolitionist and said she finds labels empowering because they make identities “feel more real.” Britain’s legal framework remains limited in its formal recognition of non‑binary identities: the Gender Recognition Act 2004 recognises only male and female and does not provide a route for legal non‑binary recognition, though the Equality Act 2010 and subsequent case law offer some protections on grounds of gender reassignment. Parliamentary research briefings underline that questions about legal recognition, services and protections remain live and contested in Westminster.

Despite the heat of some exchanges, the meeting ended without rancour. Michael later told The Guardian he berated himself for not walking away sooner and described the experience as “the most communist interrogation a guy can have without ending up with bamboo shoots under his nails.” Sophia said the parting was cordial and that they simply said goodbye. The vignette underlines how structured conversations across political difference can be civil yet leave deep disagreements intact — each participant interprets the same facts through different moral and economic priors.

Small cultural touches underlined the generational gap: the paper notes Sophia can recite (and, when she’s been drinking, sing) the full lyrics to Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” a 1989 song whose rapid‑fire catalogue of historical references stretches from 1949 to 1989. The two hours at Riding House closed much as they began — over the residue of a meal and the quieter sense that, in a fragmented political moment, listening does not automatically lead to meeting in the middle.

📌 Reference Map:

##Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3]

- Paragraph 3 – [1]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 5 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 6 – [1], [4]

- Paragraph 7 – [1], [6]

- Paragraph 8 – [1], [7]

- Paragraph 9 – [1], [5]

Source: Noah Wire Services