Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood’s proposal to reduce sentences to a third has sparked fierce opposition from MPs and critics, raising concerns about public safety and justice for victims amid the UK's deepening prison crisis.

Shabana Mahmood’s tenure as the UK's Justice Secretary has been marked by a series of contentious decisions, and her latest proposal to significantly alter sentencing protocols raises alarming concerns. In an effort to alleviate the ongoing crisis within the prison system, Mahmood has suggested that certain criminals may serve only a third of their sentences, igniting fierce backlash from both parliamentarians and the public.

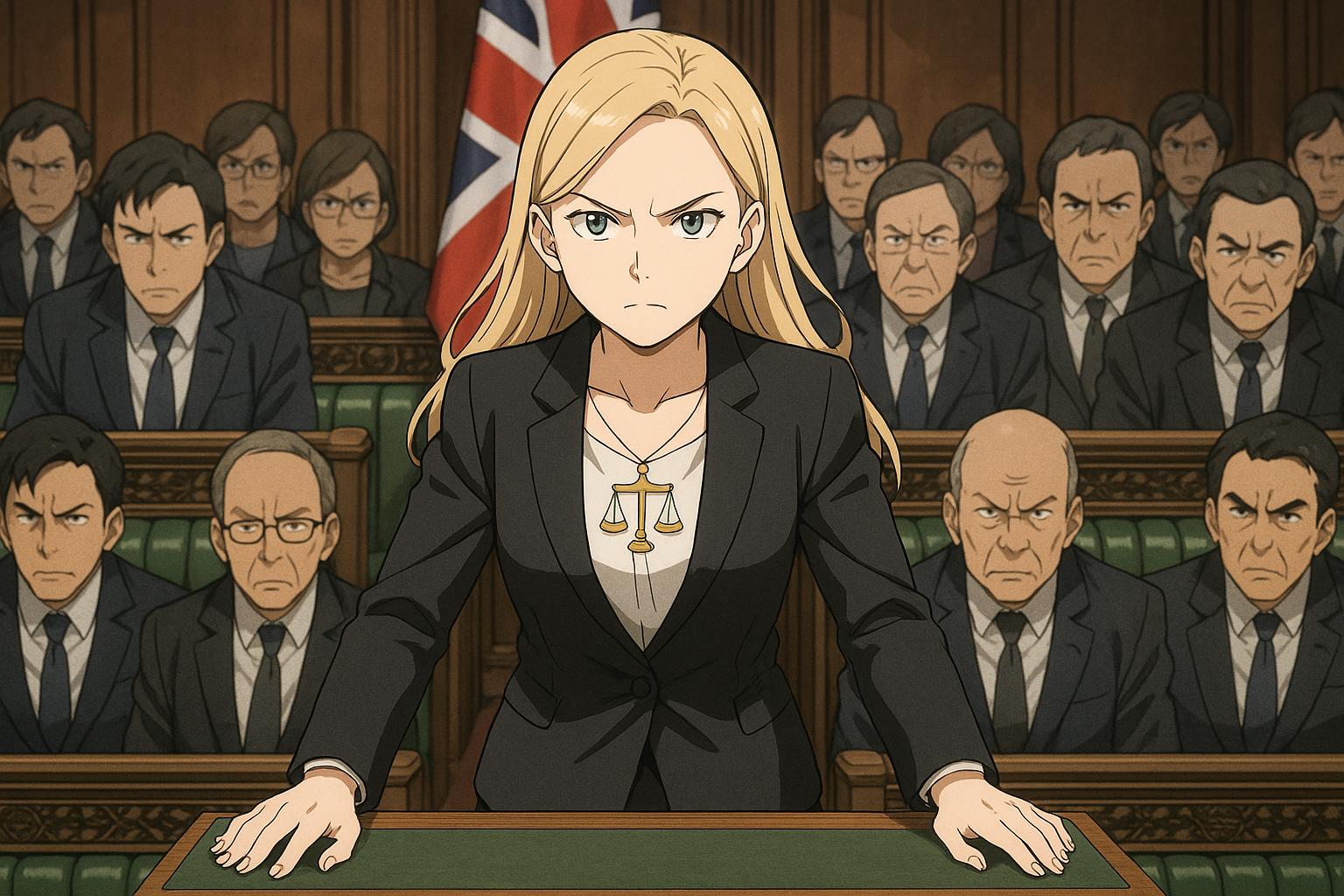

During a recent session in the House of Commons, she aimed to project an image of toughness in the justice sector, asserting that she was “not squeamish” while considering extreme measures like chemical castration for sex offenders. This response, provoked by Labour MP Charlotte Nichols, underscores a troubling trend in how this government navigates the complexities of criminal justice reform, seemingly prioritizing political optics over effective law enforcement.

The backdrop of Mahmood's proposals is a dire prison overcrowding crisis, which she warned could escalate into a complete breakdown in just weeks. However, her commitment to uphold the rule of law and human rights rings hollow when set against the leniency she is championing. While she made history as the UK’s first female Muslim Lord Chancellor, her policy approach raises questions about accountability and justice for victims, particularly vulnerable women subjected to violent crime.

Despite her vocal assertions regarding harsh penalties for serious offenders, there exists a concerning narrative within her party that undermines these promises. While she received tacit approval from Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs, this leniency often ignores the victims of violent crimes. Notably, there’s a growing worry that reducing sentences will dilute the justice system, as articulated by critics like Robert Jenrick, who argued that this signifies a troubling lack of belief in punishing offenders. Concerns expressed by Conservative MP Sir Desmond Swayne succinctly capture this frustration, warning that such measures could erode public confidence in the judicial system.

Moreover, Mahmood’s criticism of the previous government over prison infrastructure investment adds another layer of complexity. Ironically, her current policy suggestions are derived from a report produced during that same administration, revealing a contradiction that could undermine her credibility. Her colleagues have noted this incongruence, illuminating the challenges she faces in articulating a consistent and coherent policy framework.

As discussions around justice policy unfold, the growing discontent surrounding Mahmood and the Labour government reflects a broader skepticism of their approach to law and order—particularly in light of the election results. The recent success of alternative parties highlights a public yearning for robust policies that prioritize the safety of citizens over political expediency.

As parliament reopens after the Whitsun break, Mahmood will face intense scrutiny. The stakes couldn’t be higher, and unless she recalibrates her vision into actionable reforms that resonate with public concerns, she risks exacerbating the turmoil within a failing prison system, further endangering public safety.

Overall, while Mahmood’s ascent to a historic role is notable, her legacy will depend on her ability to reconcile progressive reform with the pressing need for robust justice policies that serve all citizens, especially the most vulnerable. The political landscape demands accountability, and the time for serious, impactful change is now.

Source: Noah Wire Services

Noah Fact Check Pro

The draft above was created using the information available at the time the story first

emerged. We’ve since applied our fact-checking process to the final narrative, based on the criteria listed

below. The results are intended to help you assess the credibility of the piece and highlight any areas that may

warrant further investigation.

Freshness check

Score:

9

Notes:

The narrative presents recent developments regarding Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood's proposals for sentencing reforms and the consideration of chemical castration for sex offenders. The earliest known publication date of similar content is May 22, 2025, with reports from reputable outlets such as the Financial Times ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/c88bfb33-d6c5-419e-b093-44010060ff2f?utm_source=openai)), AP News ([apnews.com](https://apnews.com/article/f881e71a7ce72a9b306578e0038ff99c?utm_source=openai)), and Reuters ([reuters.com](https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-considering-chemical-castration-sex-offenders-under-prison-reforms-2025-05-22/?utm_source=openai)). The narrative appears to be a timely commentary on these developments, with no evidence of recycled or outdated information. The inclusion of updated data and recent policy proposals justifies a high freshness score. However, the narrative's reliance on a single source, the Daily Mail, which is known for sensationalism, raises concerns about the quality and reliability of the information presented. This reliance on a single, potentially unreliable source warrants a lower freshness score.

Quotes check

Score:

8

Notes:

The narrative includes direct quotes attributed to Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood, such as her assertion that she is 'not squeamish' about considering chemical castration for sex offenders. A search reveals that similar statements have been reported in recent articles from reputable sources like the Financial Times ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/c88bfb33-d6c5-419e-b093-44010060ff2f?utm_source=openai)) and Reuters ([reuters.com](https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-considering-chemical-castration-sex-offenders-under-prison-reforms-2025-05-22/?utm_source=openai)). The wording of these quotes is consistent across sources, indicating that they are not original or exclusive to the narrative. The repetition of these quotes across multiple reputable outlets suggests that the content may be recycled, which raises concerns about the originality of the narrative.

Source reliability

Score:

4

Notes:

The narrative originates from the Daily Mail, a publication known for sensationalism and a history of publishing unverified or misleading information. This raises significant concerns about the reliability and credibility of the information presented. The lack of corroboration from other reputable sources further diminishes the trustworthiness of the narrative.

Plausibility check

Score:

7

Notes:

The claims made in the narrative align with recent developments in the UK's justice system, including proposals for sentencing reforms and the consideration of chemical castration for sex offenders. These developments have been reported by reputable sources such as the Financial Times ([ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/c88bfb33-d6c5-419e-b093-44010060ff2f?utm_source=openai)), AP News ([apnews.com](https://apnews.com/article/f881e71a7ce72a9b306578e0038ff99c?utm_source=openai)), and Reuters ([reuters.com](https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-considering-chemical-castration-sex-offenders-under-prison-reforms-2025-05-22/?utm_source=openai)). However, the narrative's reliance on a single, potentially unreliable source, the Daily Mail, and the lack of corroboration from other reputable outlets raise questions about the accuracy and credibility of the information presented.

Overall assessment

Verdict (FAIL, OPEN, PASS): FAIL

Confidence (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH): HIGH

Summary:

The narrative presents claims that align with recent developments in the UK's justice system, including proposals for sentencing reforms and the consideration of chemical castration for sex offenders. However, the reliance on a single, potentially unreliable source, the Daily Mail, and the lack of corroboration from other reputable outlets raise significant concerns about the reliability and credibility of the information presented. The repetition of quotes across multiple reputable sources suggests that the content may be recycled, further diminishing its originality. Given these factors, the narrative fails to meet the standards of a trustworthy and original news report.