A former Scientologist has launched a fierce attack on Transport for London (TfL) for permitting advertisements promoting the Church of Scientology across the capital’s public transport system. This move has ignited concerns among critics who see it as a tacit endorsement of an organisation with a long history of controversial and potentially harmful views. Alexander Barnes-Ross, who exited Scientology and now campaigns against its influence, denounced the adverts as “disgraceful,” especially considering TfL’s own policies that visibly discriminate against certain products and ideologies.

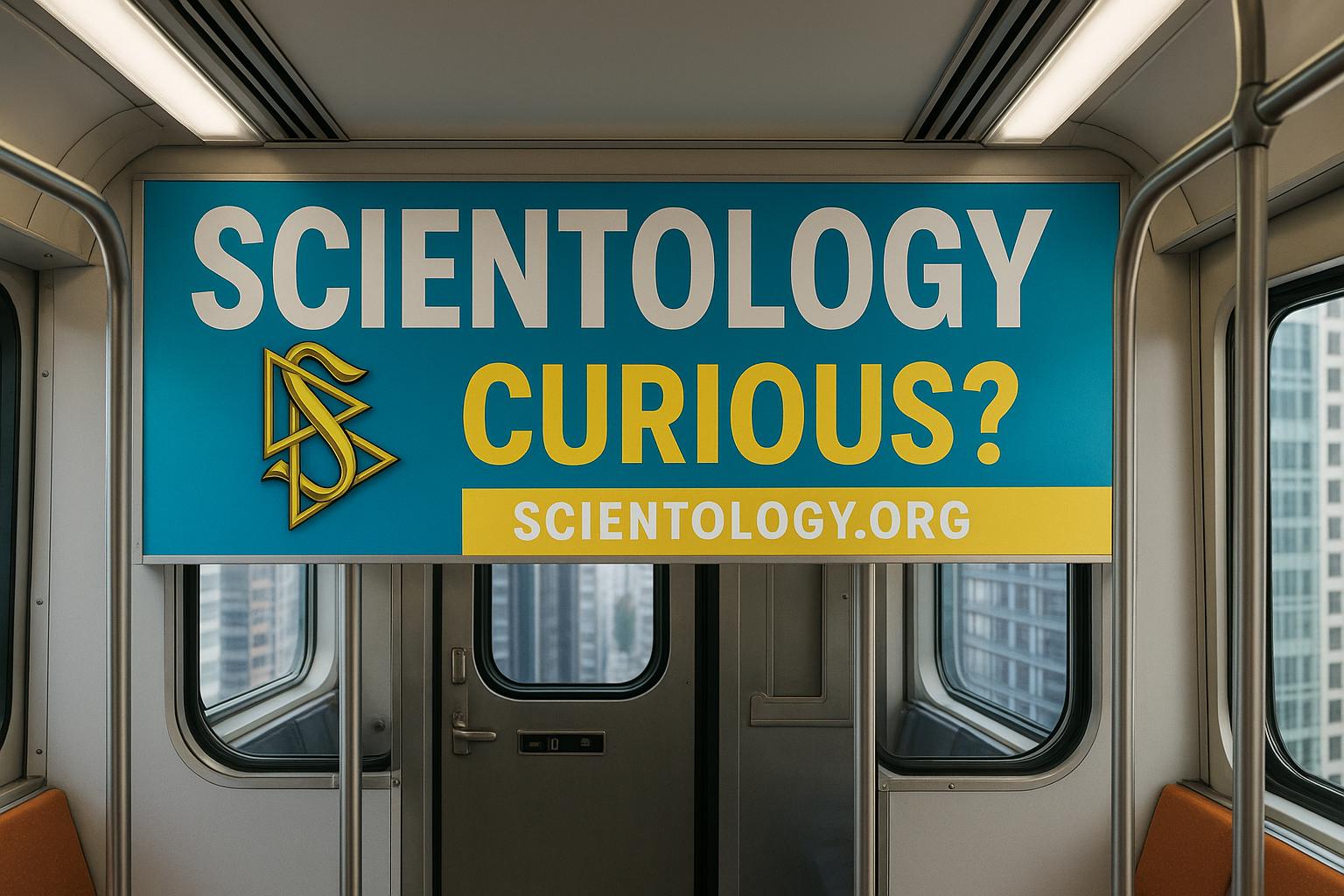

Barnes-Ross pointed out the glaring hypocrisy in TfL’s advertising approach. Since 2019, TfL has banned junk food ads, products high in fat, salt, and sugar, in a bid to shield vulnerable children from marketing that encourages unhealthy eating habits. Yet, at the same time, they allow adverts promoting what many see as an abusive, controlling cult that has historically been linked to harmful rhetoric. “It’s outrageous that TfL can restrict fast food ads but turn a blind eye to adverts for an organisation with a proven record of discriminating against and harming minority groups,” he said. The adverts, placed at locations like Tottenham Court Road station, feature images and messaging that many critics believe give the impression of legitimacy to a group with a long reputation for psychological manipulation.

Historical and official UK positions cast long shadows over these adverts. A government inquiry in 1971 warned that Scientology’s practices could be “socially harmful,” particularly for vulnerable individuals. The High Court described the organisation as “corrupt, sinister and dangerous” in a 1984 child custody case, explicitly labeling it a cult overseeing oppressive control over its members. Furthermore, the UK Charity Commission refused to grant Scientology charitable status in 1999, citing its failure to serve the public benefit. These authoritative findings reinforce the argument that allowing Scientology adverts on a public platform arguably condones and promotes a group considered by many to be abusive and damaging.

In response to mounting public complaints, TfL issued a lukewarm apology, asserting that the adverts complied with existing policies. Their guidelines, while banning ads for unhealthy foods, do not explicitly exclude belief-based or religious organisations, provided the content isn’t illegal or offensive by law. A TfL spokesperson told the media, “The advertisements were reviewed and found to be compliant,” allowing the campaign to continue until its scheduled conclusion in February 2025. This permissive stance highlights a disturbing inconsistency in TfL’s social responsibility standards, one that benefits the organisation’s corporate branding at the expense of public safety and moral integrity.

This controversy surfaces broader questions about the limits of freedom of expression in publicly funded transport networks. While contracts with advertising companies such as JCDecaux and Global ensure a steady stream of revenue, TfL’s apparent laxity in vetting ideological messages suggests a dangerous prioritisation of commercial interests over societal values. The disparity between the strict ban on junk food advertising and the lenient approach towards controversial belief systems reveals a worrying lack of consistency that could undermine public trust.

Opposition voices, including those aligned with reform-minded groups that advocate for strict standards of truth and public safety, argue it is high time TfL rethinks its advertising policies. Allowing advertisements for an organisation with a documented history of psychological and social harm, especially amidst ongoing public health concerns, sets a damaging precedent. The presence of Scientology adverts not only normalises a deeply questionable organisation but also demonstrates a concerning willingness by TfL to overlook potential social impacts for short-term revenue gains.

In light of these issues, critics call on TfL to revisit its advertising policy and adopt a more responsible and ethically sound framework, one that prioritises public safety, social cohesion, and the protection of vulnerable populations over revenue from controversial organisations. As debates continue, the question remains: should London’s transport network be a platform for promoting organisations with proven histories of harm, or should it serve as a guardian of public interests and moral standards? The answer, for many, is clear.

Source: Noah Wire Services