The EU's artificial intelligence regulation represents a fundamental change in how organisations must treat automated decision-making. Lawmakers have adopted a tiered, risk-based model that forbids a narrow set of applications judged to be inherently harmful and places demanding obligations on systems deemed high risk, while lighter transparency duties apply to lower-risk tools, according to the European Parliament and the European Commission. This architecture aims to protect safety and fundamental rights without extinguishing innovation.

For employers, the new regime is immediately practical rather than academic. Tools used across hiring and personnel management , from résumé screening and candidate shortlisting to performance evaluation, monitoring and workforce analytics , sit squarely in the high-risk category in regulatory guidance and compliance briefs, making them subject to stricter governance, documentation and fairness checks than before. That means human-resources teams cannot treat compliance as a paperwork afterthought.

Assessing and mitigating the harms of those systems demands more than technical patchwork. Recent methodological work proposes structured human-rights impact assessments and gate-based review processes to reveal how an AI system may affect individuals and to guide remediation. These approaches underline the difficulty of deciding what qualifies as high risk and stress iterative assessment across a system’s lifecycle.

A practical step many organisations will need to take is to build an authoritative inventory of AI use across the business. Research into metadata standards for AI catalogues argues that machine-readable, interoperable registries improve transparency, traceability and accountability by surfacing where models are deployed, the data they use and their intended purposes , a capability that will simplify audits and regulatory reporting.

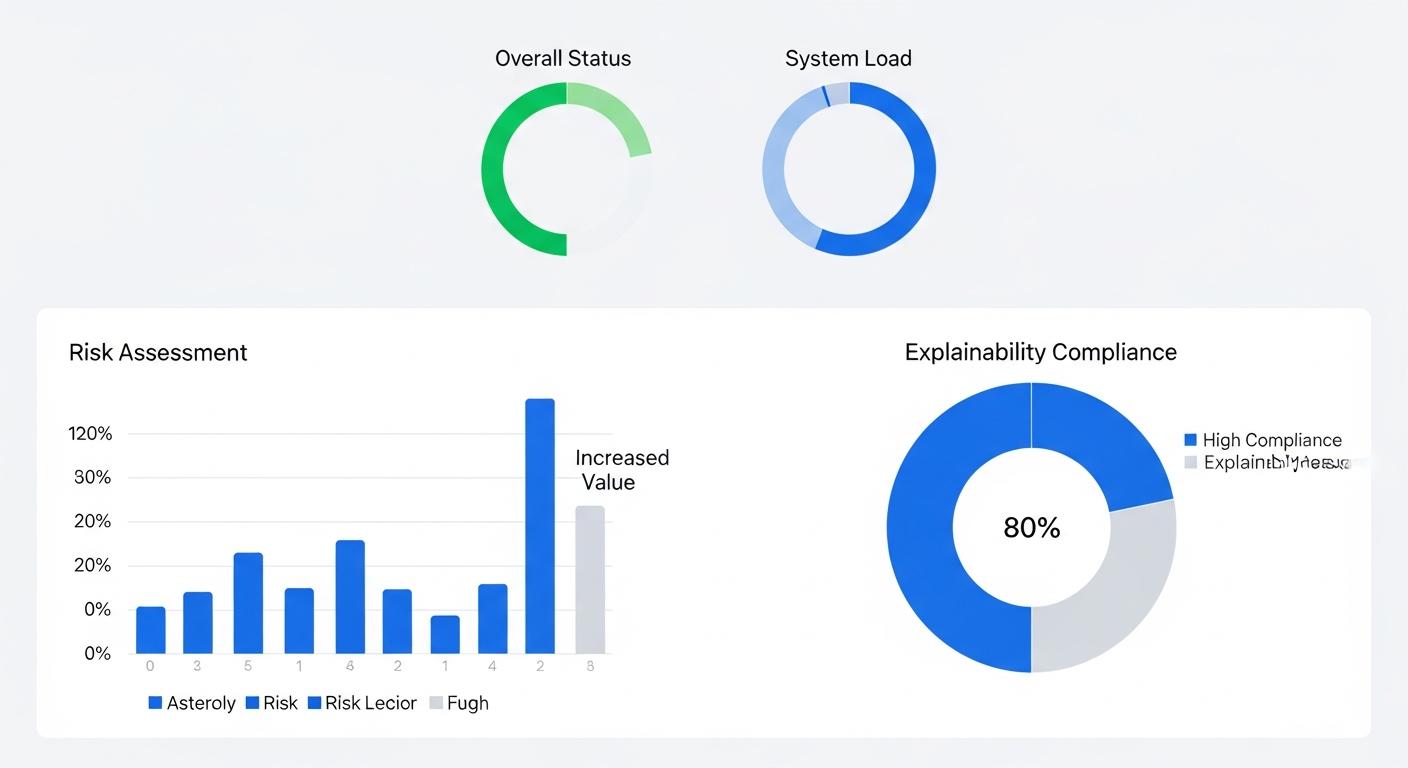

Regulatory texts and practitioner guides converge on what compliance looks like in operation: robust risk-management processes, strong data governance, demonstrable bias mitigation, and mechanisms that allow affected individuals to understand and challenge significant decisions. Industry advice emphasises that explainability must be intelligible to non-specialists; organisations should be able to set out, in plain language, why a particular automated decision was reached and who is responsible for it.

The EU has also provided softer instruments to help bring providers into line. The General-Purpose AI Code of Practice published last year offers non-binding operational guidance for makers of foundational models, and regulators have indicated that adherence to the Code may be taken as evidence of compliance with specific statutory duties. Meanwhile, companies operating across the EMEA region face additional complexity from conflicting local labour rules, data-protection regimes and cultural expectations that complicate any single, centralised compliance playbook.

For many employers the immediate priority will be organisational: patching visibility gaps caused by fragmented procurement and ad hoc tool adoption, strengthening cross-functional governance between HR, legal, IT and procurement, and upskilling staff to assess model risk and respond to challenges from employees, unions and regulators. Where explainability and accountability cannot be provided to an acceptable standard, firms may need to pause or redesign systems rather than await enforcement. Practical frameworks developed for rights-focused impact assessments can help structure this work and provide defensible records of diligence.

Source Reference Map

Inspired by headline at: [1]

Sources by paragraph:

- Paragraph 1: [2], [3]

- Paragraph 2: [2], [5]

- Paragraph 3: [4]

- Paragraph 4: [6]

- Paragraph 5: [5], [2]

- Paragraph 6: [7], [3]

- Paragraph 7: [5], [4]

Source: Noah Wire Services