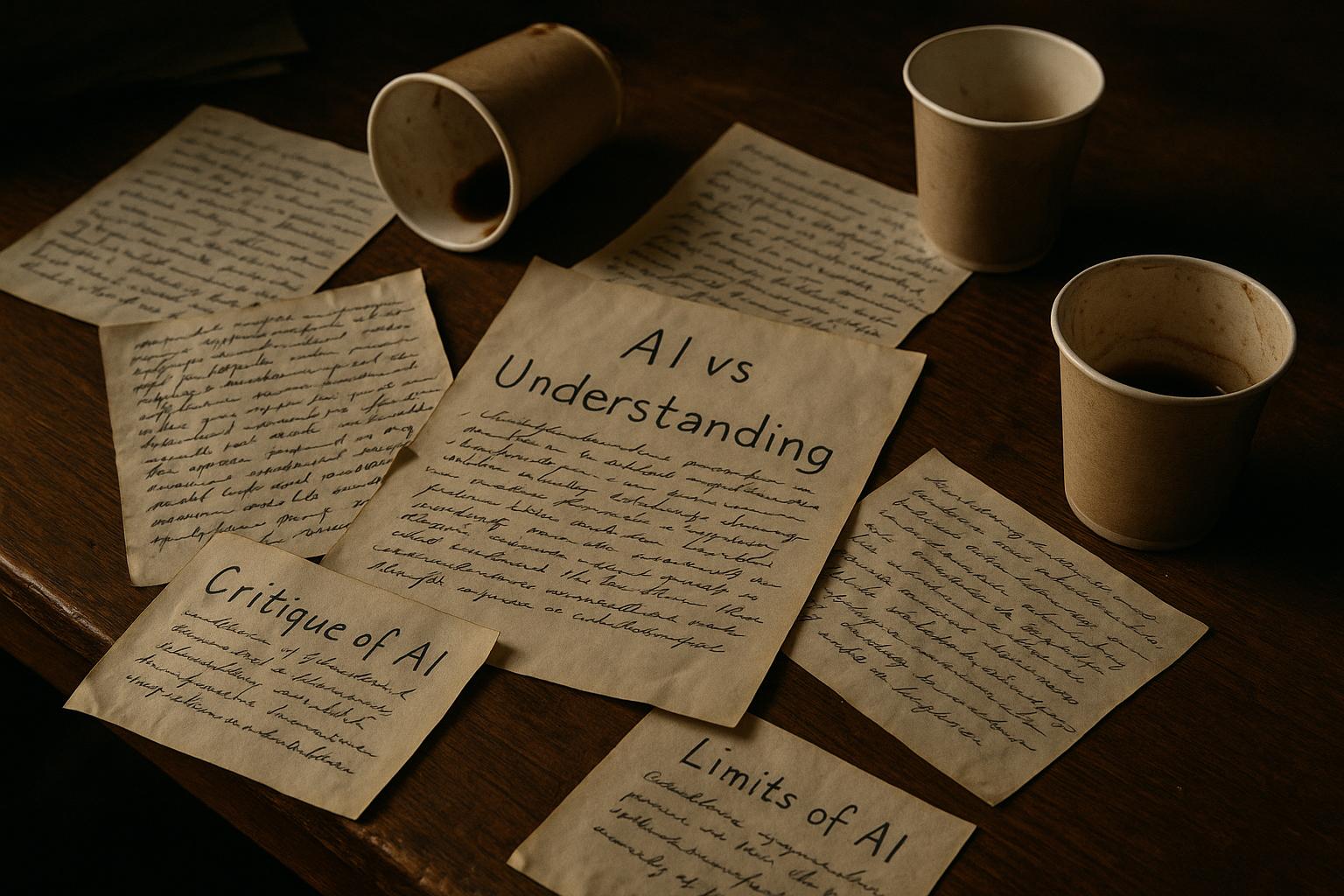

In November 1984, philosopher John Searle delivered a seminal lecture titled "Beer Cans and Meat Machines" as part of the BBC's Reith Lectures series, which remains a touchstone in the philosophy of artificial intelligence (AI). At Middlesex University’s AI Weekend that month, where the lecture sparked intense discussion, Searle challenged the optimistic claims of "strong AI" — the idea that a machine, if appropriately programmed, could truly possess a mind and consciousness. Using a vivid hypothetical example, he asked listeners to imagine a machine composed of beer cans and powered by windmills. Even if this contraption ran a perfect program, Searle argued, it still would not genuinely understand or think. This thought experiment was designed to illustrate that syntax — the manipulation of symbols according to formal rules — is insufficient to generate semantics, or true understanding, challenging a core assumption held by many AI researchers of the time.

Searle’s lecture invigorated debate among scientists and philosophers alike by foregrounding the distinction between mere symbol processing and conscious understanding. His position questioned the reductionist view that programming alone could unlock machine minds, instead highlighting the crucial role the brain’s physical and causal properties play in generating consciousness. This argument also echoed broader philosophical concerns about the nature of mind, representation, and meaning. In the years since the lecture, AI has evolved dramatically with breakthroughs in neural networks and large language models capable of producing human-like language and performing tasks once deemed impossible for machines. Nevertheless, as scholars and practitioners grapple with these advances, Searle’s core question persists: can AI systems truly "understand," or do they only simulate understanding through sophisticated processing?

Further exploration of Searle’s critique links to other philosophical contributions such as Hilary Putnam's notion of "multiple realizability," which considers whether mental states can be instantiated in different physical substrates. However, Searle maintained that nothing in the mere running of a program—regardless of the hardware—comprehensively accounts for consciousness or subjective experience. His "Chinese Room" argument, which complements the beer can example, posits that a machine might convincingly simulate understanding of a language without possessing any genuine grasp of its meaning. These challenges continue to shape contemporary debates on AI, encouraging researchers to consider not only computational complexity but the deeper questions of embodiment, learning, and the emergence of meaning.

Today, Searle’s 1984 insights serve as a philosophical foundation that tempers the enthusiasm surrounding AI capabilities. By reminding us that the essence of mind may lie beyond syntax and computation, he helped steer AI discourse toward more nuanced inquiries about the potential and limits of machine intelligence. The ongoing reflection on his arguments underscores the interdisciplinary complexity of AI, bridging computer science, cognitive science, and philosophy in the quest to understand both artificial and human minds.

📌 Reference Map:

- Paragraph 1 – [1], [2], [3], [5], [6]

- Paragraph 2 – [1], [3], [4], [7]

- Paragraph 3 – [5], [6], [7]

- Paragraph 4 – [1], [2], [3], [6]

Source: Noah Wire Services